Karen Davis, PhD presented this topic on the panel “Where Did Our Compassion Go? Children, Adults and the Loss of the Human-Animal Bond,” The City College of New York, December 2, 2014. She is presenting it at the 2017 Animal Rights National Conference in Washington, DC on Saturday, August 4th.

My background with children and young people

I grew up in Altoona, Pennsylvania in the 1950s, where my father and three brothers and virtually the entire male community took sport hunting and fishing for granted without question. I never participated in their activities or had any desire to, though my father would sometimes invite me to join them, “just for the walk.” I could say no, but my brothers could hardly refuse. Boys are as much at the mercy of “male domination” and punishment for deviance as girls are, and sometimes more.

Through the years I’ve worked professionally with children and young people of all ages. In the 1960s, I taught at a daycare center in Baltimore, Maryland called – yes! – The Little Red Hen. In the 1970s, I was a juvenile probation officer in inner city Baltimore for five years, where I counseled troubled teenage girls. From 1980 to 1991, I taught English at the University of Maryland-College Park to students who often sought my counsel not only about literature and writing, but also about themselves. Thus I have had many interactions with a variety of children and young people over the years, and my views on the effect of socialization on the human-animal bond have been shaped by these encounters.

Source of this discussion

My discussion is inspired by the English Romantic poet William Wordsworth (1770-1850), whose poem Ode on Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood recounts his loss of visionary insight into Nature as he became an adult.

The poem begins:

There was a time when meadow, grove, and stream,

The earth, and every common sight,

To me did seem

Apparell’d in celestial light,

The glory and the freshness of a dream.

It is not now as it hath been of yore; –

Turn wheresoe’er I may,

By night or day,

The things which I have seen I now can see no more.

In the poem, Wordsworth argues that children enter the world with a light of perception that fades over time “into the light of common day.” Seeking to understand the loss of this light, he describes how children, despite their affinity for Nature and the bliss this gift confers, are driven simultaneously to imitate and please their parents. Wordsworth views the eagerness of children to model and fit into the adult world as a tragic but inevitable motivation that, unbeknownst to the innocent ones, guides them into “the darkness of the grave.” Toward the end of the poem he asks the child:

Thou little Child, yet glorious in the might

Of heaven-born freedom on thy being’s height,

Why with such earnest pains dost thou provoke

The years to bring the inevitable yoke,

Thus blindly with thy blessedness at strife?

Full soon thy soul shall have her earthly freight,

And custom lie upon thee with a weight,

Heavy as frost, and deep almost as life!

This is a rhetorical question, but one that seeks an answer. Wordsworth finds solace in his belief that there are compensatory forms of adult happiness commensurate with the hard realities that Life brings, and that despite the loss of visionary joy in Nature that comes with growing up, there remains in each person a “primal sympathy” that custom cannot destroy.

Children are not blank slates

The seventeenth-century English Enlightenment philosopher John Locke (1632-1704) argued in opposition to Wordsworth that the mind of a child at birth is an “empty cabinet,” a blank slate or tabula rasa devoid of innate ideas or content. Whereas Wordsworth argues that people are born with a supernal knowledge that informs the young child’s perceptions and enthusiasms, which he regards as positive attributes that socialization stifles, Locke views the human infant as an empty vessel whose content develops from the elements of each person’s life experiences. Locke said, “I think I may say that of all the men we meet with, nine parts often are what they are, good or evil, useful or not, by their education.”

Modern genetics disproves the idea that individuals come into the world as blank slates. Instead, we each have a unique genetic blueprint. As noted on microworld.org, “Almost every cell in your body contains DNA and all the information needed to make you what you are, from the way you look to which hand you write with.” As for Wordsworth’s idea that children possess an inextinguishable primal sympathy with Nature, even if so, the question remains as to how, and why, biology, psychology, aging and socialization conspire to smother this primal sympathy as part of the growth process in most people. Must socialization conflict with compassion for animals?

Let us note that compassion for animals as individuals is not synonymous with primal sympathy with Nature. Wordsworth’s own passion for Nature had more to do with waterfalls and woods than with animals per se, and being a Nature enthusiast can involve treating animals badly. Worship of animal Spirits and concern for animal Species can coexist with callousness toward individual animals, even disdain for a “mere” bird or a single squirrel.

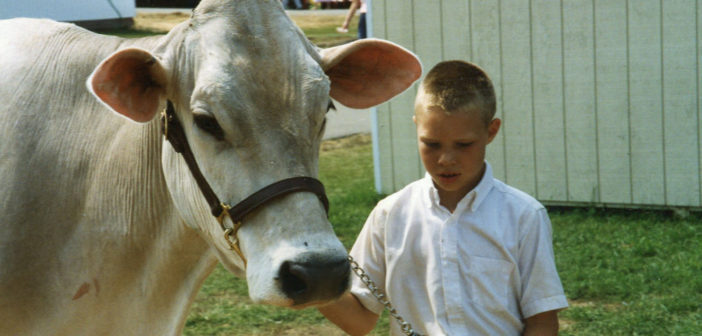

4-H crushes compassion for animals

Writing in the anthology Sister Species: Women, Animals, and Social Justice, farmed animal transport and slaughterhouse investigator Twyla Francois describes her experience growing up in a small, religious farming community in Manitoba, Canada. In rural Canada, she writes, almost all students are enrolled in the 4-H – Head, Heart, Hands, and Health – program, where they learn to suppress their feelings of compassion for animals. She recalls how her friend, who unknowingly was raising her beloved calf to be auctioned for slaughter, wept as the calf was loaded onto the trailer to be taken away and killed. Immediately, the organizer handed her a check for $1,000. “To my surprise,” Twyla writes, “her tears were quickly replaced with thoughts of how she would spend the money.”

What this episode shows is complicity between the “child” and the elements of adult callousness – not just between Twyla’s friend and the auction organizer, but within the girl herself. The elements of socialization include desires, satisfactions and compensations that compete with and often overwhelm empathy and compassion, not only for animals but for anyone. Socialization is not simply an outside force bearing down on innocent children. Like all animals who live in herds and flocks, humans have evolved to be socialized in order to live within their own group.

Being a child vs. being socialized

In “At First Blush,” in the December 2014 issue of Harper’s Magazine, Norwegian writer Karl Ove Knausgaard describes a childhood episode in which he was shamed by his teacher in front of the class. He goes on to consider what it means to be a child:

To be a child is to be within yourself, inside your thoughts and feelings. To be a child is to be free of the perceptions of others. To be a child is also always, in a certain sense, to be inconsiderate. Your own needs, your own hunger, your own thirst, your own joy, your own anger – these direct everything you do. To grow up is to learn to show consideration, to know who you are in the company of others, and to act in relation to them, not only to yourself. Shame is our way of regulating this relation. Shame is the presence of the gaze of others within ourselves. This is what I experienced back then, in the classroom.

Knausgaard discusses the role of shaming – bullying – in socialization. Bullying isn’t so much learned behavior as it is instinctual. Children will bully a deviant without any help from adults. This “dark side of childhood,” while cruel and pitiless toward the victim, acts as a social correction. Without bullying, he says, there would be no rules or sense of belonging to a community – “just individuals who would each be forced to create and maintain their own separate worlds.” The cost and benefit of being part of a community is that the “deviant” (the individual or that part of the individual that differs) has to be sacrificed. “It is the price we have to pay to be more than one,” he says.

Where Did Our Compassion Go? City College of New York, Dec. 2, 2014. Left to right: Chris Parucci, Bill Crain, Karen Davis, Brian Shapiro, Nancy Cardwell, Joyce Friedman, Daisy Dominguez

Ethical deviance and socialization

Psyche and socialization are complicated, but let us assume that there is a compassionate “child” – a primal sympathy for animals – in most of us. One of the saddest ironies in life, I believe, is that there are adults in every community who love and empathize with animals, but who don’t know that there are others among them who feel the same, because everyone keeps quiet about it. Fear of ridicule and rejection, isolation and ostracism, enables people to bully one another into silence and submission. Ethical deviance challenges the tyranny of custom and compliance.

Ethical deviance is the element in society that prevents socialization from becoming sclerotic. The ethical deviant opens the window a crack to let in fresh air, fresh ideas and perceptions. The ethical deviant may be thought of as the “child” within a society who, luckily for that society, will not grow up to be just another replica. The ethical deviant reassures people whose sensibilities have not gone totally underground or been beaten to death that they are not “crazy” for caring about a chicken. The ethical deviant refuses to be bullied into becoming a slave or a clone in order to belong. The ethical deviant provides a social service.

In a very valuable sense then, the “child,” aka ethical deviant, is a grownup. In his Ode on Intimations of Immortality, Wordsworth contrasts his instinctual, unreflecting passion for Nature as a child with the “years that bring the philosophic mind.” The ethical deviant’s primal sympathy with and insight into the life of things matures to become the conscious sensibility, awareness and purposefulness of the adult. This person is the poet, the peacemaker, the social justice activist, the animal rights advocate – the “outsider” who keeps the consciousness and conscience of society alive and growing.

The struggle between conscience and callousness isn’t just between the self “in here” and society “out there”; the struggle takes place among conflicting impulses within our nature in response to situations we find or put ourselves in. Running a sanctuary for chickens, I can tell you that whereas I like mice and raccoons ontologically, I am not fond of them situationally. There is an ethical struggle among competing forces, feelings and obligations even within a sanctuary and a sanctuary provider. For some people it may be that being or becoming vegan changes them to feel more peaceful inside, but as I once wrote, this hasn’t been my experience. Rather:

Veganism has made me more conscious of behavior patterns that are not consistent with my adherence to philosophic veganism. Being vegan has not made my personality more peaceful, as by some sort of physiological or mystical transformation or holistic purification; however, it has made me intellectually more aware of my feelings and behavior and less able to rationalize and do certain things that I might otherwise overlook.

An important point is that we must never assume that people “over 25” are unreachable, unteachable, or dispensable in our quest. Not only is this assumption wrong, but children who are surrounded by adults who don’t support their compassionate feelings suffer in lonely isolation and confusion. Such children will often turn against themselves and the animals violently for having feelings that no one they looked up to when they were little seemed to share or understand. Our best hope for the future isn’t five-year-olds. Our best hope is five-year-olds supported by adults who have nurtured their own primal sympathies to maturity.

KAREN DAVIS, PhD is the Founder and President of United Poultry Concerns, a nonprofit organization that promotes the compassionate and respectful treatment of domestic fowl including a sanctuary for chickens in Virginia. She is the author of Prisoned Chickens, Poisoned Eggs: An Inside Look at the Modern Poultry Industry; More Than a Meal: The Turkey in History, Myth, Ritual, and Reality; The Holocaust and the Henmaid’s Tale: a Case for Comparing Atrocities; A Home for Henny; and Instead of Chicken, Instead of Turkey: A Poultryless “Poultry” Potpourri.

KAREN DAVIS has chapters in Sister Species: Women, Animals, and Social Justice; Experiencing Animal Minds: An Anthology of Animal-Human Encounters; Defining Critical Animal Studies: An Intersectional Social Justice Approach to Liberation; Animals and Women: Feminist Theoretical Explorations; Critical Animal Studies: Thinking the Unthinkable; Critical Theory and Animal Liberation; Terrorists or Freedom Fighters: Reflections on the Liberation of Animals; and Meat Culture (2016). In 2002 Karen Davis was inducted into the National Animal Rights Hall of Fame for Outstanding Contributions to Animal Liberation. http://www.upc-online.org/karenbio.htm

Karen Davis, PhD, President

United Poultry Concerns

12325 Seaside Road, PO Box 150

Machipongo, VA 23405

Office: 757-678-7875

Email: Karen@UPC-online.org

Website: http://www.upc-online.org

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/UnitedPoultryConcerns

Featured image: boy leading cow at 4-H. Courtesy Kim Bartlett – Animal People, Inc.