In respect of Black History Month and the anniversary of the founding of the Black Panthers Party for Self-Defense, this post is dedicated to commemorating the Black Panthers and exploring what animal defenders can learn from them today.

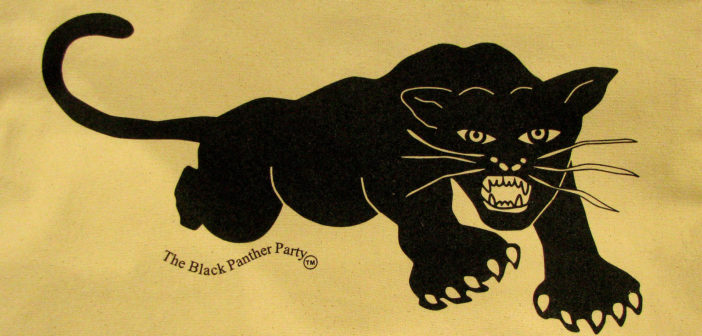

My intention here is to spotlight this radical organization, a famous movement for Black power, which chose to be represented in the name and image of an animal: a panther. But to avoid de-contextualizing Black herstory and appropriating it for the struggle of animal rights – something that unfortunately happens all the time – the focus here is going to be about openly acknowledging this expression of Black resistance for what it was and who it was for.

For more information on the social context that the Panthers were born into, all that they accomplished, and their continuing legacies, read here and here.

Propaganda and the past

When assessing social movements, such as the movement for Black empowerment against white supremacy in the United States, there are always campaigns to smear, discredit, confuse and silence. Mainstream society selectively remembers in order to be self-serving for current social circumstances. This happens all the time, through the media, the government, and the education system. You can recognize it in what is said, and what is not said, in who is given space to speak, and who is not listened to.

This is why so often people have been told to believe that the Black Panthers, a radical organization for Black empowerment, was something akin to a white supremacist hate group and terrorist organization.

Within a single year of their existence, the Black Panthers were being targeted by the FBI’s special counter-intelligence program called COINTELPRO, which according to the FBI’s own documents, was intended to “expose, disrupt, misdirect, discredit, or otherwise neutralize the activities of the Black nationalists.”

This included targeting Martin Luther King Jr., until his assassination in 1968 by the same U.S. government, and many leading Panthers. The Panthers were such a target that 233 out of 295 documented actions taken by COINTELPRO to disrupt Black groups were directed against the Black Panther Party. (For more on COINTELPRO, check out Democracy Now!)

As a result of such institutionalized racism, when learning more about the Black Panthers it is common to find that much of the deeper herstory is bound up in oral memories, remembered by the Black lives who choose to share accounts of what really happened. Please respect the very real, very common, and very beautiful tradition of oral herstory as a valuable and legitimate marker of time past.

1. Finding inspiration from the animals

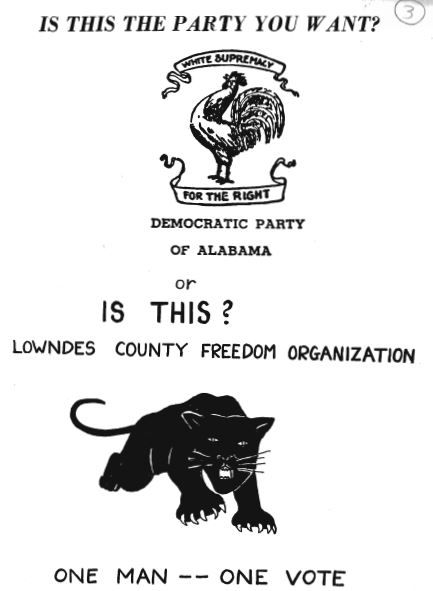

The Black Panther Party for Self-Defense was founded in Oakland, California in 1966 by Huey Percy Newton and Bobby Seale. With permission, they took their name from the Alabama-based Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO), an independent political party with the symbol of a snarling black panther, which was also known, more commonly, as the Black Panther Party.

the LCFO formed in part to protest the barriers to Black enfranchisement that had for decades kept every single Black person of voting age off the county’s registration books. This was because the state of Alabama had the infamous “literacy test,” which was intended to deny illiterate people the right to vote. It was not a coincidence that that the state’s education system continued to be heavily segregated, leaving Black education grossly underfunded and Black people more often illiterate. As a result, many voters could not actually read the names of the political parties or candidates on the ballots. So instead, many people would simply vote for the picture symbol on the ballot.

While the whites-only Democratic Party of Alabama featured a white rooster along with the slogan “White Supremacy for the Right,” and illiterate white voters were instructed to “vote for the rooster,” the emergence of the LCFO offered a black panther vote for Black illiterate voters.

But why the black panther? From a 1966 speech, “How the Black Panther Party was Organized,” LCFO chairman John Huler talked about how,

“… this black panther is a vicious animal as you know. He never bothers anything, but when you start pushing him, he moves backwards, backwards, and backwards into his corner, and then he comes out to destroy everything that’s before him.”

Newton affirmed that sentiment, saying they adopted the black panther as their symbol not because the black panther doesn’t strike first, “but if the aggressor strikes first, then [the panther will]attack.” This representation of the panther, as an animal who would resist violently only as a last resort, meant that the animal became a symbol of Black resistance. Given that the animal too was Black, they came to represent the poor and downtrodden in the Black belt.

The black cat was hung in the windows of countless households and small businesses and put on placards and t-shirts of Black community members as they organized and went on strike for tenant rights. After one neighborhood successfully gained control of a landlord’s property to thereafter establish one of the first community-owned, affordable housing projects in the country, the sentiment was that it was “all thanks to the power of that big black cat.”

All this is an important lesson for animal defenders, who frequent adopt animal names for their grassroots organizing. It is important because often we can fixate on representing non-humans as perpetual victims of the system, as forever innocent and passive bodies that need our intervention to give them liberation. Even further, this flawed portrayal of animals tends to fuel ally theater behavior, when vegans too begin to see themselves as victims.

But with this representation of the black panther as someone who is courageous and controlled in their use of strength, we can see why so many people drew inspiration from the animal. From this depiction of the black panther as dangerous only when provoked, humans found their own inner strength by following the example of an animal. I think that is something we could all try doing more.

2. Clearly defined goals

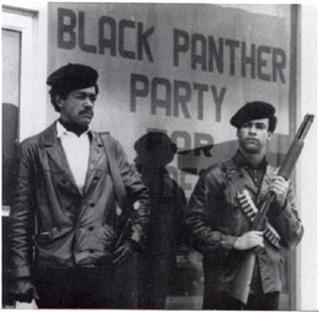

The Black Panther Party for Self-Defense sought social justice for Black communities through a combination of revolutionary theory, education, and community programs. While the mainstream tends to fixate on the Panthers being a group of proud gun-carrying Black people (and the white fear that came with that), many of the lead organizers clearly and repeatedly explained that their goals were about empowering the Black community in the face of a racist system.

The Panthers went further in clarifying their vision, creating the Ten-Point Program. This list explained their revolutionary ideology in the form of ten demands, which detailed what they wanted and needed in their efforts to regain their Black communities.

The plan contained very basic demands, like that of self-determination, decent housing, full employment, inclusive education and an end to police brutality. It also included radical demands, like that of full exemption from the war draft, effective prison abolition for all incarcerated Black men, and a national vote in which only Black people would be allowed to participate (to determine their “national destiny”).

Here, Seale delivers a speech outlining these 10 demands:

As you can see, the Panthers were explicit in keeping these goals clear and in plain language for everyone to understand. But more than that, in keeping their goals straightforward by demanding freedom and bread, the system was less capable of distorting their vision through misrepresentation in the media. Similarly, the Panthers were able to remain more accountable to each other in their opposition to oppressive social systems.

A strong example of this is how outspoken the Panthers were in their opposition to the war in Vietnam. They recognized it as an expression of U.S. imperialism against people of color, and so were unapologetic in refusing to support the capitalism and racism of war-mongering in East Asia.

Quoting Black Panther Party founder Bobby Seale:

“We do not fight racism with racism.

We fight racism with solidarity.

We do not fight exploitative capitalism with Black capitalism.

We fight capitalism with basic socialism.”

This is an important lesson for animal defenders too, who often struggle to articulate the goals of animal liberation, and what realizing those goals might look look like for humans and animals. So often, discussions about animal advocacy look like debates about abstract theories and long sermons about morality, all of which is largely inaccessible to understand but also relatively useless in daily lives of most people.

Of course, the system exploits this weakness and misrepresents animal advocates as privileged foodies naively day-dreaming. Because beyond the broad statements of wanting to “free animals,” it is rare to find examples of plain-language demands that express what exactly is needed to create space of sanctuary for earthlings in the short and long term.

So let’s take note of this too, and start making simple, radical demands about what we want for the animals and how we plan to achieve it.

3. Organizing for self-defense

Because the U.S. is a nation founded on white supremacy, there was and still is a very real danger of white supremacists oppressing and harming Black communities.

White supremacy looks like high unemployment, unsafe housing, police brutality, poor health care, and inferior educational opportunities within the Black community. And white supremacy also looks like the Ku Klux Klan attacking Black voters.

During the 1960s, there were different organizations forming to offer different solutions for achieving Black empowerment. This happened in major urban centers with large Black populations, like Harlem, Chicago and Detroit, with organizations like the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and the Nation of Islam.

When the Panthers adopted the panther logo, which was already familiar to communities across the Black belt of the U.S., they also issued a statement about self-defense. By doing this they were making it clear that safety and preservation against racism was a core element of their efforts for empowering Black people in inner cities of the North and on the West Coast.

Organizing for self-defense among the Black Panthers had many different manifestations, including the famous police patrols. During police patrols, Panthers would listen to police calls on a short wave radios so that they could arrive at scenes of police arrests of Black people, to both discourage police brutality and to help inform the people being arrested of their constitutional rights.

Another radical example of Black self-defense was Seniors Against a Fearful Environment (SAFE), a safety service to oppose elder abuse in public. Started at the request of a group of senior citizens for the purpose of preventing muggings and attacks, the program offered free transportation and escort services.

This certainly does not translate to mean that animal advocates are being targeted in the same way as Black people organizing against racism. It does mean that we need to keep each other safe, both us humans advocates and wider animal communities. This can and should look like different things, largely depending on community capacity and the struggles faced within each space.

For example, some groups could focus on protecting animal companions, like with volunteer emergency search squads for lost dogs and cats in a certain neighborhood, or seasonal efforts providing water in summers and shelter in winters. There can be others focusing on animals to be exploited for capitalism, such as hosting regular vigils to document animal cruelty at slaughterhouses. Whatever the community or those endangered, the goal is to devise sustainable ways to keep each other safe from violence.

4. Transformative community building

The Panthers were advocates of what they called “revolutionary inter-communalism,” which was essentially a socialist approach to resolving local issues by sharing the responsibilities of building the community. The underlying concept here was Black self-determination, of “survival until revolution.” The Panthers were fostering circumstances where Black people could be organized and survive outside the racist systems that were under-servicing the Black community.

In practice, this looked like the more than 60 Survival Programs created by the Panthers, where community members created social institutions and public services within the community itself and without relying on outside relief. Some of the most radical services included:

- The Black Student Alliance, for creating concrete programs on campus that would unify the student body through “free books and supplies, a free transportation program, child care services, a financial aid program, a food program serving good, nutritious food at reasonable prices, and initiation of relevant courses along with the demand for better instructors.”

- The Youth Institute, for Black children to “learn to their highest potential and to strengthen their minds so that one day they would be successful.”

- The Free Food Program, to supplement the groceries of Black and poor people until “economic conditions allowed them to purchase good food at reasonable prices.”

- The Black Panther Intercommunal News Service, publishing regularly every week and distributed nationally. At the height of popularity the circulation was more than 100,000 copies per week.

- The People’s Free Medical Centers (PFMC), offering services such as “testing for high blood pressure, lead poisoning, tuberculosis and diabetes; cancer detection screenings; physical exams; treatments for colds and flu; and immunization against polio, measles, rubella, and diphtheria.”

- The Free Breakfast Program, which by 1970 was being served in 19 cities, providing 20,000 children full free breakfasts before school.

Of course, the above are incredible examples of community organizing against oppression, so this is something all animal allies should take good notes about. If we want communities to have easy access to living vegan and to working jobs outside the animal industrial complex, we need to understand that we are the only ones who will make this happen.

Instead of relying on the lies of capitalism or the illusions of “democratically-elected” governments, we too need to create our own circumstances of self-determination for all earthlings. So instead of waiting for another corporation to make a vegan option available, start with producing local food systems and organic gardens through indigenous-led land sovereignty. Instead of taking the role of a vegan savior approaching strangers, we need to start within our own communities by creating space for free services to help those interested in unpacking species privileges.

5. Empowering female leaders

The Black Panthers had an incredible record of female representation. By the early 1970s the movement was almost two-thirds female. Even more, several chapters were headed by womyn and the head editors of the Black Panther Party newspaper were always all womyn.

This helps explain why the Panthers were so progressive in female empowerment, officially supporting womyn’s reproductive rights, including abortion. Similarly, with womyn exclusively in control of the media and authority positions, there was more opportunity for body-positive politics to enter into conversations around Black empowerment.

Listen here to Cleaver talk about why Black is beautiful:

This is not to say that the Panther Party was without its definite faults internally and incidents of sexism and sexual harassment. However, when Fred Hampton was acting as the deputy chairman of the Illinois chapter he was outspoken in condemning sexism, regarding it as counter-revolutionary.

In particular, there have been four womyn who became core representatives of what the Panthers were saying and trying to accomplish:

- Elaine Brown‘s leadership saw that the Black Panther’s Survival Programs grew at their most rapid pace and the original ideas of the party hit their strongest mark. Still today, at West Oakland Farms, Brown is helping ex-cons by giving them ownership in urban farms.

- Kathleen Cleaver was the party’s National Communications Secretary, meaning the Panther’s spokesperson. Cleaver has gone on to graduate from Yale Law and today acts a professor at Emory University. check out this more recent interview with her on #BlackLivesMatter.

- Angela Davis came into national prominence in August 1970 when she was put on the FBI’s 10 most wanted list for supposedly planning and providing weapons for the escape of George Jackson and other members of the Soledad Brothers. As a celebrated author she received her PhD and became a professor of history and a director for Feminist Studies at UC Santa Cruz. Davis continues to be outspoken on prison abolition.

- Assata Shakur was a member of the Panthers and the Black Liberation Army, until eventually fleeing a nation-wide “manhunt” that saw her seek political asylum in Cuba. Shakur is still in exile and was listed as a most wanted terrorist by the U.S. You can read more about that development here.

This is another excellent illustration by the Panthers of how community organizing should happen: by giving space to womyn to lead by example and to lead in ways that empower community members to be active and respected.

There you have it. Thanks for reading and don’t stop remembering.

Featured image: the Black Panther logo. Image credit rocor, CC BY-SA 2.0.