pattrice jones is an influential and accomplished activist, writer, and educator who has been involved in activism since the 1970s. She co-founded VINE Sanctuary with her partner and has authored two books (The Oxen at the Intersection and Aftershock: Confronting Trauma in a Violent World) and numerous essays, taught college and university courses, and spoken at many conferences and events. jones’ work is grounded in ecofeminism, and she excels at making visible the connections between various forms of oppression, especially speciesism and anti-LGBTQ bias.

It was a pleasure to have the opportunity recently to interview pattrice and hear her thoughts on a variety of topics. We discussed the importance of grounding one’s activism in real relationships with animals, the relationship between feminism and animal liberation, VINE Sanctuary’s rooster rehabilitation program, and her advice for animal advocates who find their compassion for humans waning.

Dylan Forest: You run a working sanctuary and also do a good deal of speaking, writing, and educating on the more theoretical side of the animal liberation movement. This is often presented as an either/or situation, but you manage both. I’m curious about your thoughts on the importance of one over the other, or how you think about finding balance between theory and action.

pattrice jones: I’m glad you asked that! If you were to visit VINE Sanctuary first thing in the morning, the first thing you would notice is how very loud it is when chickens, cows, ducks, sheep, geese, goats, turkeys and others all wake up ready to explore the day and especially ready for breakfast. You would never again be tempted to call yourself a “voice for the voiceless” because your ringing ears will have made it very clear that animals have their own voices, which they use — along with gestures and other means of communication — to express their wishes quite clearly to anyone willing to pay attention.

You might also notice one or two cows staring at you warily or that a trio of ducks is alternating between staring at you and talking to each other — clearly about you, although you can’t guess what they might be saying. I personally find it humbling to notice that ducks are talking smack about me, and you too might find your human hubris punctured by the experience of animals looking back at you. The wary cow, who is watching to make sure you don’t come too close to her calf, might help to disabuse you of any inflated notion of yourself as a hero.

If you stuck around through the morning, making yourself as unobtrusive as possible, you might have the opportunity to see the members of our multi-species community going about their days in their usual ways. From this you might learn that nonhuman animals know more than you do about some things, such as getting along with others who are very different than yourself. You might also begin to see different personalities. For example, you might notice that Bishop the goat is a sweetheart but his mother Mirana can be a bit of a jerk. That might help you resist any urge to fall for gendered stereotypes and also might lead you to avoid the all-to-common trap of pushing back against the mistreatment of animals by lumping all animals together as “sweet babies” in need of rescue by valorous humans.

In short, I think that animal advocacy must be grounded in real relationships with actual animals. Everything I have written since co-founding the sanctuary in 2000 has been grounded in my experiences. Of course, not everyone can work or live at a sanctuary, but it is still possible to take steps to ensure that whatever you are doing in the name of nonhuman animals really does reflect their realities and their interests.

So, it’s especially important for animal liberation theory to be rooted in relationships with animals. But also, in any realm of activism, I think, theory has to be informed by praxis and vice versa. As the late Nobel prize winning environmentalist Wangari Maathai said, “Until you dig a hole, you plant a tree, you water it and make it survive, you haven’t done a thing. You are just talking.”

At the same time, action without reflection often leads nowhere. Every activist and organization ought to be able to identify the assumptions about people and how the world works that underlie their strategies and tactics and be willing to revise those theories in response to new information. Activism is always a process of trial and error, and only reflection can allow us to see when we need to tweak our tactics or even change course altogether. Sometimes that’s not because we were wrong to begin with but because the situation has changed.

When you are trying to take away someone’s power or profits, they will push back, often in ways that change the terrain. For example, the phrase “factory farming” was extremely useful when it was first coined, helping to awaken many people (including many potential allies within environmental and social justice activism, as well as many consumers) to the multifaceted horrors of industrial animal agriculture. But then, of course, certain sectors of meat industry pushed back by beginning to promote allegedly humanely farmed meat. And so it became necessary to push back against that. That doesn’t mean that the initial focus on factory farming was wrong, just that situations are always evolving and our strategies and tactics must evolve as well.

While many social justice movements are now integrating an understanding of intersections between forms of oppression, such as racism, sexism, and homophobia, it seems many models of intersectionality do not yet acknowledge speciesism. Why do you see the inclusion of speciesism as important, and why should those other human-rights-centered movements be interested in incorporating anti-speciesist goals and viewpoints?

First, you must understand that the idea of intersecting or interconnected oppressions arose among social justice activists, and particularly among Black feminists, as a way of understanding how the different ways that humans oppress each other support and compound one another. In 1977, the Combahee River Collective, a group of Black lesbian feminists, put out a statement which called for an “integrated analysis” of the “interlocking” nature of “racial, sexual, heterosexual, and class oppression.” In 1981, Angela Davis published Women, Race, and Class. In 1988, Suzanne Pharr published a book entitled Homophobia: A Weapon of Sexism. In 1989, Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the term “intersectionality” while writing specifically about the workplace discrimination experienced by Black women.

All of this was happening within feminism, but I think that the broader cultural shift toward what might be called ecological or systems thinking played a role. Beginning in the 1960s and into the 1970s, the environmental movement helped the general public to see birds and lakes and other elements of nature as existing within complex ecosystems, so that using poison to kill dandelions might lead to the deaths of fishes. At about the same time, other fields, such as physics and psychology, also began shifting to thinking about systems.

Mapping even one system can be a challenging mental exercise. Thinking about how systems interact is even more arduous. The more variables you add, the more complex it becomes. I remember, when I was an AIDS activist, how long it would take to explain all of the ways that homophobia, racism, sexism, classism, and ableism all worked together to make that one disease more deadly, thereby compounding one another.

Social justice activists were late to see what is now called environmental injustice, because environmental questions seemed separate. Many still have not adequately included ableism in their theories and actions. So, it’s not surprising that it has taken some time for animals to even begin to be integrated into these analyses.

But — take heart! — within every social justice movement, there are animal advocates talking about the intersections they see. And that’s how it has to happen, as conversations among comrades. Meantime, there’s similar work to be done within animal advocacy. Too many activists and organizations try to promote veganism or advocate for animal rights as if they were doing so in a vacuum from which powerful social forces like sexism, racism, and economic inequality are absent. That’s bound to fail, because we always must take context into account. It’s also bound to fail because social injustice, environmental degradation, and animal exploitation really are linked at the root. If we do not work together to confront the ways of thinking and acting that lead us to hurt each other, other animals, and the earth, the same problems will keep recurring in new forms.

You’ve long been an advocate for an alliance between feminism and animal liberation, and have argued that one movement cannot succeed without the other. Do you see this alliance forming and growing currently, or is there still a long way to go? Do you see any particular hurdles to that alliance?

First, it’s important to know that feminism and animal liberation always have been linked, even though those linkages have not always been evident to those who focus on either one or the other. A hundred years ago, many suffragists in both the US and the UK were vegetarian anti-vivisectionists. Nearly 40 years ago, the late Marti Kheel and others founded Feminists for Animal Rights. Thirty years ago, Carol Adams published The Sexual Politics of Meat. Girls and women are much more likely to be vegan than boys and men. The vast majority of animal rights activists always have been, and still are, women.

I would say that the biggest hurdle to any formal alliance between the two movements is men in the animal advocacy movement. On the one hand, we still have too many men who are either actively perpetrating violence against women or standing idly by rather than taking the initiative to hold other men accountable for such abuses. On the other hand, we have men who make facile use of our ideas, shouting that “YOU CAN’T BE A FEMINIST AND EAT MEAT” as if they were the arbiters of feminism or flinging around words like “rape” without due care for the impact of such words on survivors of sexual violence.

What we need men in the movement to do instead is to hold themselves and each other accountable for the continuing sexism in and outside of the animal rights movement. It’s not enough to be vaguely supportive of women’s rights or superficially opposed to violence against women. Interrogate and oppose toxic masculinity in all of its manifestations, including but not limited to those that directly hurt animals. Do the hard work of talking to other men about hunting, fishing, rodeos, and other forms of animal abuse perpetrated primarily by men. Don’t worry yourselves about feminists unless you have done enough real work against sexism to call yourself one.

This is not to say that there are no feminists who resist calls to confront their own speciesism. But those are conversations that must go on —and are going on—within feminism. Trust that we are handling it.

Now, I am noticing that I answered that question in that way because it was a man asking. For those readers who are themselves feminists, male or female, here’s are some tips for having those conversations productively:

- I find it useful to use “I statements” when talking with non-yet-vegan feminists about animal exploitation and liberation. “I feel uncomfortable with…. I can’t participate in…. When I learned [some awful thing about the dairy industry], I felt….”

- Feminists are rightly concerned with bodily self-determination, and—because patriarchy polices women’s bodies and especially women’s weight—this can take the form of feeling that any critique of what someone else chooses to eat is an attack on autonomy. So, I make sure to acknowledge that feeling in some way and then say the magic phrase, “eating meat is something you do to someone else’s body without their consent.”

- I am myself a survivor of sexual violence and have worked with survivors of both rape and childhood sexual abuse. While the word “rape” doesn’t trigger me and I know that some survivors who are vegan do use it to talk about what happens to cows and other animals at farms, labs, zoos, and other sites of exploitation, I also know that some survivors are very sensitive to that word and will not hear anything else you say after you say it. In general, highly emotive words like “rape” and “murder” tend to spark nervous system responses that are not conducive to thinking clearly about challenging ideas. Why take that risk? Instead, I find it much more effective to calmly describe what is done to female animals in terms that are more likely to provoke empathy than defensiveness. I might even say, “Can you imagine?” I imagine it myself as I am speaking. I remember one time, speaking to both students and faculty of a women’s studies department, reflexively gripping my own breasts as I described mechanical milking and glancing out at the audience to see that several others were doing the same. After that talk, one faculty member walked past the podium with her coffee cup looking queasy and saying “that’s it, I can’t even finish this latte, no more dairy for me.”

- I also use the language of feminism without making a big show of doing so. For example, I may say something like “if you eat cheese or eggs, that’s a relationship with female animals — a relationship of power and control” knowing that “power and control” is a phrase used concerning domestic violence and that most feminists are against relationships of power and control.

- In general, evoke empathy and call to already-existing ethical commitments in ways that awaken and empower the wish to be in better relationships with nonhuman animals and nature. I always assume that of course my feminist comrades will go vegan once they understand. It’s important to really feel that people can and will change, because any hint of hostility or accusation of hypocrisy will do the opposite of what you intend.

One example at VINE sanctuary that makes the intersection between sexism and speciesism obvious is your work rehabilitating roosters used in cockfighting. Can you tell me a little bit about what this process entails and why it is a feminist project?

For millennia, in numerous cultures around the world, roosters have been seen as avatars of masculinity. The blood “sport” of cockfighting reflects and reinforces that association. We recognize roosters used in cockfighting as traumatized birds abused in service of a spectacle of masculinity. They fight because they are terrified and unsocialized (and often drugged), not because of any inherent aggressiveness. Our rehabilitation program allows roosters to recover from the trauma in safety and to learn the social skills they need by watching other roosters getting along with one another and resolving their conflicts without bloodshed, as the wild relatives of roosters still do in the jungles of South Asia.

Our advocacy for roosters recognizes that the law and order approach to cockfighting, which persists despite being illegal in all 50 states, cannot solve the problem. We must undermine the stereotypes of roosters, which are, not coincidentally, the stereotypes of toxic masculinity. One fascinating fact about cockfighting is that many of the men who actually raise and handle the roosters are deeply devoted to them, spending hours on end caring for them. They truly believe that the fighting is natural and that they are helping the birds be their true combative selves. So, in addition to undermining those stereotypes, we also have to offer boys and men ways to be in relationship with animals in ways that are truly caring while still feeling sufficiently masculine. I hope it’s clear why this is a feminist project.

It can be hard for some people to hear about animal liberation without thinking it means that human liberation will be put on the back burner. What would your response be to a feminist who argues that, for example, comparing the objectification of female animals in our food system to that of human women is offensive and belittling to women?

It’s speciesism that makes the comparison seem belittling, and so — no matter who you are — you won’t get anywhere by making the comparison before tackling speciesism head-on. If you’re not yourself a feminist, making clumsy comparisons to topics of great importance to feminists is even less likely to be effective. And, it’s really not OK for anyone to hijack someone else’s suffering to make a point. It’s one thing for a member of an oppressed group to talk about the connections they see between animal exploitation and the things that they or their ancestors have experienced. It’s another thing altogether for, just for example, a a non-Jewish person who has never taken any action against anti-semitism—and perhaps even holds anti-semitic ideas, since they have never interrogated themselves about that—to make simplistic comparisons to the holocausts.

I’m suspicious of comparisons in general. I think that people mostly make them thinking that this will be an easy way to get a point across — X is like Y, we all agree that X is bad, so you must agree that Y is bad too — but, in reality, you mostly end up arguing about whether X really is like Y, defeating the whole point of making the comparison.

Listen: The things that are done to cows on dairy farms, to take just one example, are hurtful and wrong in and of themselves—not because they are similar to ways that human females have been and continue to be violated. Yes, we do need to understand those similarities, but that’s not so that we can convince feminists to be vegan, that’s because cows and girls alike are ensnared in a unified system of objectification, degradation, and exploitation.

So, while those of us who are feminists can and do talk with other feminists about how our own feminism led us to be vegan, I think that animal advocates in general ought to stick to directly describing the things that are done to female animals in ways that are likely to evoke empathy for them. You don’t have to say much more than, “I’m not comfortable with participating in that kind of violence against female animals” to provoke your feminist friends to consider—probably in the privacy of their own conscience rather than in dialogue with you—whether they really are comfortable with that.

One alliance I don’t see discussed nearly as often is that between queer liberation and animal liberation movements. What might be an example of an issue those two moments could join forces to address?

As an LGBTQ-led farmed animal sanctuary, we’ve been talking about this particular intersection for nearly 20 years. Starting in about 2002, we began holding “Queering Animal Liberation” discussions, workshops, and interactive lectures all over the country as well as abroad. So many insights have come out of these exercises in collective cognition that I cannot begin to summarize them here.

So, let me do what you ask and give an example linked back to an earlier answer: What feminists sometimes call “toxic masculinity” not only leads to violence against women and animals but also motivates homophobic and transphobic hate crimes. This version of masculinity also leads men to be less likely to be environmentally responsible… or to care for their own health! That’s just one of the ways that toxic masculinity hurts boys and men themselves. And, yes, it’s probably a big factor in refusal to protect oneself and others from COVID-19. But that suggests a way to reformulate masculinity: to focus on using one’s strength and courage on truly protecting others rather than on shows of dominance. (I personally would prefer to get rid of the gender binary altogether, but so many people’s identities are so vested in gender that that is probably an impossible dream.)

Another linkage is what some ecofeminists call “reprocentrism,” which is itself embedded into the inherently harmful economic system of capitalism. This is the source of much of the bias against non-reproductive sexuality. Within every sort of animal exploitation, nonhuman animals are forced to reproduce whether they would choose to do so or not.

Many would not. Despite the mythology of animals as automatons relentlessly focused only on reproduction, members of hundreds of species regularly engage in same-sex affection, pair-bonding, and sex. That mythology — perpetrated in nature programs, children’s books, and zoo exhibits — hurts animals by making them seem like insentient robots. But it also hurts LGBTQ people by making homosexuality seem “unnatural.”

Unfortunately, many people who fight for animal liberation become very jaded about humans because of the cruelty they are capable of, and can even slip into oppressive ways of thinking about humans. I see this a lot when I’m moderating the comments on our Facebook page, often in the form of wishes of violence towards humans, or explicitly racist and xenophobic comments about the “other” people who are perceived to be most cruel towards animals. How would you respond to someone whose thinking has gone down this path?

I think it’s important to distinguish between bias and true revulsion at human cluelessness and cruelty. Discrimination, exploitation, and violence among humans are part of the problem with people. If you are sickened by people, you will be sickened by those things as well. Being disgusted with humans as a whole will not lead someone to suddenly start spouting racist or sexist slurs.

So, we simply cannot allow anyone to use animals to disguise their own bigotry. Any bigotry they express is their own, and has nothing to do with animals. Animals are, in fact, injured any time one of their self-appointed advocates uses them in this way. That’s one reason why all vegan and animal advocacy organizations ought to be including anti-bias work within their own efforts.

It certainly can happen that animal advocates, especially those who do hands-on work with animals who have been injured by humans, can begin to find it hard to feel compassion for people. If that’s you, then the thing to do is to recognize that this diminished compassion is a symptom of your own distress. Time for some self-compassion and self-care! Also, for so long as you are unable to feel empathy for humans, you should refrain from trying to do advocacy work that involves dialoguing with people or publicly opining about people. Persuasion requires empathy, and you will not be able to be effective if you are unable to feel compassion for people. Instead, devote your energies to some of the 10,001 behind-the-scenes tasks needed by the movement: Research, data analysis, graphic design, event logistics, and hands-on care for rescued animals are just some of the things you can do without running the risk of alienating the very people that animals need us to persuade to change their behavior.

Finally, I often say that “the problem with vegans… is that they are people.” Homo sapiens is a deeply compromised species that seems to have reached the limit of its ability to solve problems. If you are reading this, then you are a human. When critiquing the ideology of human supremacy, try to remember that those ideas probably have influenced your own self-conception. Vegans are no less likely than other humans to inflate ourselves at the expense of others or to be unaware of the ways that feelings are coloring our purportedly rational thinking. The more you are able to set aside your own hubris, the better able you will be to help others stop believing that they are superior to nonhuman animals.

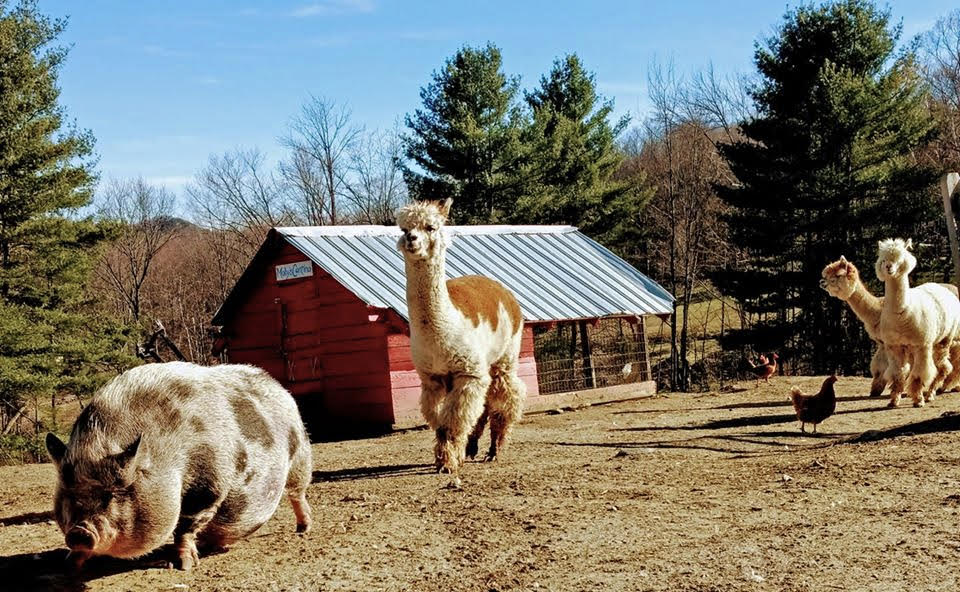

Featured image: pattrice jones with Luna, a resident at VINE Sanctuary. This image and all images in this story via pattrice jones.