Since 2001, Animal People has co-sponsored the Asia for Animals conference. This year, the AfA was held in Kuching, Malaysia from October 6-10 (learn more). During the two weeks beforehand, Animal People executive director Wolf Gordon Clifton traveled in Indonesia visiting different animal welfare-related projects. This series of articles, “Archipelago Animal Adventures,” is intended as a travelogue to document what he saw, for the benefit of activists in Indonesia and across the world striving to improve animal welfare in the archipelago.

Unless otherwise marked, all photos are free to use for non-commercial purposes, as specified under CC BY-NC 4.0.

Previous:

Winds of Change Along the Java Sea: Archipelago Animal Adventures, Days 1-2

Escape From Raptor Island: Archipelago Animal Adventures, Day 3

Night of the Fire Face: Archipelago Animal Adventures, Days 4-5

Vegan Punks of Yogyakarta: Archipelago Animal Adventures, Day 6

Day Seven: Wednesday, September 30th

I got only a short night’s sleep before waking up to my alarm at 3:00 AM. Today I had reserved for a little tourism, visiting the historical sites of Borobodur, the world’s largest Buddhist temple, and Prambanan, the largest Hindu temple in Indonesia, both built during the 9th century by competing dynasties. My tour bus left Yogyakarta at 4:00, so as to make it to Borobudur in time to watch the sun rise from atop a nearby mountain ridge.

The morning’s early start was difficult, but it was completely worth it to witness such a beautiful dawn. Borobudur began the day enshrouded in thick mist, which quickly dissipated under the red glow of the sun rising directly above. A little to the southeast, I could see smoke trickling from atop the volcano Merapi. I meditated for a short while, and opened my eyes to an exceptionally beautiful, but fleeting, sight as the sun briefly shone at just the right angle to make every green leaf in the jungle around me glow like crystals of emerald and peridot.

- Forested ridge before dawn

- Forest before dawn

- Smoke coming off Merapi

- Sunrise

- Sunrise

Arriving at Borobudur proper, I found the surrounding area to be more developed than I had been led to expect, with large gardens and many shops and food stalls catering to tourists. However, the temple itself was still every bit as majestic as I had hoped.

Built to accord with Buddhist cosmology, Borobudur is structured in three main levels, corresponding to the Realm of Desire, Realm of Form, and Realm of Formlessness. The first and lowest represents our own level of reality, the Realm of Desire, governed as it is by attachment to passing sensations, emotions, and desires, which produce suffering. Borobudur’s Realm of Desire included many reliefs of animals, who in Buddhism share our same spiritual nature and can reincarnate as humans and vice-versa.

- Approaching Borobudur through the gardens

- Sculpture at base of staircase

- Navigating the Realm of Desire

- Continuing…

- Monkeys, goats, birds, and other animals

- Monkeys, goats, birds, etc.

- Elephant, horses, and people

- Various birds

- Elephant, cow, and pigs

- Woman kneeling to horned ungulate

- Woman kneeling to elephant

- Elephant in lifelike posture

- Animals in Realm of Desire, and illumination beyond

- Monkey embracing cow

- Lion on the hunt

- Lion and other animals

- Lion and other animals

- Humans and bird-faced humanoid

- Giant turtle

- Ship under attack by sea monster

- Turtle saves the sailors from monster

- Sailors kneel to turtle

- Monkey couple sharing food

- One monkey comforting other during migraine (?)

- One monkey standing on other’s shoulders to get food

- Hunters shooting at monkeys (No! I was really sad to see the monkey couple’s story end like this)

- Buddha and birds

- Humans and horses

- Exquisitely detailed ship

- Looking up toward Realm of Form

- Headless buddha in Realm of Form

- Buddha looking down from Realm of Form

- Buddha in Realm of Form

The next level up is the Realm of Form, inhabited by bodhisattvas (buddhas-to-be) who have focused all their attentions on the goal of enlightenment. Appropriately, the reliefs in this realm mostly depicted spiritual seekers and the buddhas they emulate, with few images of passion or violence as in the level below.

- Realm of Form as seen from ground

- Realm of Form as seen from ground

- Part of temple under restoration

- Guard lion near staircase

- Buddha in Realm of Form

- Walking through the Realm of Form

- “No Smoking” sign, and a headless buddha used to hold up a tarp. Desecration of the temple, or a spiritual reminder that all things are impermanent?

- Town and golden-domed mosque, looking out from Realm of Form

- Buddhas

- Buddha

- Buddha or bodhisattva surrounded by animals

- Buddhas

- Rows of buddhas

- Rows of buddhas

- Buddha surrounded by disciples

- Buddha surrounded by humans and animals

- Looking upward toward the Realm of Formlessness

Finally, at the temple’s summit I reached the Realm of Formlessness, the abode of enlightened beings who have transcended the limits of space and time. Unlike in the lower levels, the walls here were blank. The only sculptures were those of buddhas meditating peacefully inside perforated stupas, detached from the sensations of the physical world around them.

- Looking down at progress so far

- How far we’ve come…

- Entrance to Realm of Formlessness: through the jaws of Yama, the Lord of Death

- Passing through the jaws of Yama, onward past death and impermanence…

- The Realm of Formlessness

- The walls are blank of artwork

- Stupas

- Stupas

- Each stupa contains a buddha inside

- For some reason, most buddhas are headless. Borobudur was found in ruins and restored, so perhaps heads were stolen by looters?

- Stupas, one open to reveal buddha inside

- Buddha in open stupa

- Buddha in open stupa

- Notice the insect on the buddha’s head

- Buddha and insect

- Insect atop a buddha statue in Borobudur temple

- The summit of Borobudur

- Looking past stupas toward mountains in the distance

Once I had descended from Borobudur’s summit back down to Earth, it took a surprisingly long time to find my way back to the parking lot, navigating a long labyrinth of shops, gardens (with confined animals), and a museum containing a real-life seaworthy replica of the ship carved in detail in the Realm of Desire.

- Real-life replica of temple ship

- Temple ship

- The ship has traveled the world, showing the ancient Javanese were advanced seafarers

- Instruments for traditional Gamelan orchestra

- Dove in cage

- Dove in cage

- Fish in fountain

- Fish in fountain

- Looks like a rooster, but with rainbow-colored crest… special breed, hybrid with another pheasant, or artificially dyed?

- Oddly colored rooster in big cage

- Oddly colored rooster

- Oddly colored rooster

Next stop was Prambanan, a Hindu temple from roughly the same era as Borobudur, built by a competing dynasty that favored Hinduism over Buddhism. Like Borobudur, it had fallen into ruin over the centuries, until restoration began in the early 20th century. An earthquake in 2006 destroyed much of the temple all over again, and while most of the central temple courtyard has been rebuilt, many of the surrounding structures are still just piles of rubble.

- Ramayana Ballet. I would have loved to attend this if I had more time in Jogja.

- Approaching Prambanan

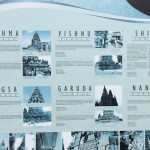

- Info placard on the different deities and their shrines

- Rubble and restoration in progress

- Restoration workers (and/or archaeologists?)

- Restoration in progress

- Prambanan courtyard

- “Restored 1932”

- Circling one of the shrines

- Relief of battle scene featuring horses and elephants

- People in horse-drawn chariot

- Angelic beings with bird bodies and human heads

- Guard lion?

- People and monkeys… scene from the epic Ramayana?

- Rama talking to monkey? In Ramayana, hero Rama recruits an army of macaques led by monkey god Hanuman to aid in war against demon Ravana

- Monkey army

- Monkey army

- Battle scene featuring demons and snakes

The temple is dedicated to the Trimurti, the Hindu trinity of three primary deities: Brahma the Creator, Vishnu the Preserver, and Shiva the Destroyer, each a manifestation of the one supreme being Brahman. Being the most favored deity in ancient Indonesian Hinduism, Shiva’s temple is the largest and centermost. Notably, Brahma’s shrine had by far the fewest tourists inside and around it. Although all members of the Trimurti are theoretically equal, in practice Vishnu and Shiva have always received far more worship than Brahma. Hindu mythology offers several explanations why, most citing a divine curse on Brahma for his extreme egotism, which has in the past enabled demons to obtain world-destroying powers from him via flattery. I found it funny that even in Prambanan, desacralized for centuries and now visited mostly by non-Hindu tourists rather than worshipers, the curse on Brahma would still seem to apply.

- Brahma the Creator

- Brahma

- Shiva the Destroyer

- Shiva was most popular with tourists

- Entrance to Vishnu temple

- Vishnu the Preserver

Across the courtyard from each deity’s shrine is another, smaller one for their animal companion or vahana. Shiva’s companion, Nandi the bull, is the only one present. The other two – Angsa, the swan of Brahma, and Vishnu’s mount Garuda, a humanoid bird of prey – are missing, presumably looted or destroyed over the centuries.

- Entrance to Nandi shrine

- Nandi the bull, Shiva’s companion animal

- Angsa and Garuda’s shrines were both empty

A number of deities lesser to the Trimurti are represented in miniature shrines around Prambanan, though most of the icons themselves are missing. In the side alcoves of the Shiva temple, I found intact statues of Durga, Ganesha, and a deity I could not identify, but whose trident indicated he was a manifestation of Shiva himself.

- Durga, wife of Shiva and the goddess of force. The bull she tramples upon is not Nandi, but Mahisha, her buffalo-shaped demon nemesis.

- Ganesha, Shiva’s elephant-headed son, the god of fortune and remover of obstacles

- Unidentified deity holding trident, a traditional icon of Shiva

Like Borobudur, Prambanan was surrounded by a maze of shops and side attractions, including birds in cages and a fenced yard full of deer. The deer generally looked physically healthy, but were somewhat overcrowded, had insufficient shade from the hot sun beating down, and lacked much in the way of behavioral enrichment besides interacting with visitors through the fence.

- Rooster roaming free in playground

- Hawk-eagle in small aviary

- Hawk-eagle

- Gruesome display of taxidermied animals (poached?) in shop

- Deer pen

- Deer interacting with tourists

- Deer huddled together in shade

- Deer

- Deer

- Deer

- Deer

- Buck

- Buck and doe

- Deer in shade

- Deer through fence

The tour was over by about 2:00 PM. While I waited for Ina to pick me up from the bus stop, I ventured into a nearby marketplace, only to find it was none other than the Pasty wildlife black market which Mr. Dana, my driver between Jakarta and Cikananga, had told me about. I was sickened at the misery of the animals I saw inside, which included numerous birds captured from the wild as well as domestic cats, rabbits, guinea pigs, and chickens, most crammed into small, dirty cages with no relief from the hot midday sun.

Out of respect for the enormous suffering of these animals, and the scale of the wildlife trafficking crisis they represent, I have decided to dedicate a full separate article to what I saw in Pasty and in the Jatinegara market of Jakarta two days earlier:

Markets of the Damned: Wildlife For Sale in Indonesia

After Ina picked me up, we went to see Animal Friends Jogja’s cat sheltering facility in another part of the city. There I met a number of friendly cats fortunate enough to have been rescued, as well as volunteers Nana and Yani, sisters, and their elderly mother. A couple dogs were also present, and one chicken, who had until recently been part of a flock. Tragically, an unknown disease struck and killed off all of her flock mates in just a matter of days, leaving her the sole survivor.

- Front porch of cat shelter

- Kitty under vehicle

- Cat

- Cat

- Cat

- Playful kitty…

- …despite being blind in one eye

- Volunteers Nana and Yani, sisters, and their mother

- Cat

- Back yard of cat shelter

- Cats

- Sole surviving chicken and cat

- Shelter yard

- Kitty

- Kitty

- Kitty

- Cat

- Kitten in closed-off nursery room

- Kitten

- Kitten

- Mother cat nursing kittens

- Ina holding kitten with Yani

- Nana with kitten

- Nana with kittens

- Room set aside for spay/neuter

- Lazy cat

- Cat on table

- Yani holding cat, showing deformity in waistline. Someone had tied around her belly as a kitten, nearly killing her as she grew and the tie dug into her flesh.

The AFJ cat shelter faced many challenges, being run out of a household on volunteer labor, with limited funding and resources, but seemed to be pretty good at improvising solutions. One of the most serious problems they regularly face is cats getting loose from the shelter and eating poisoned food, generally put out by neighbors to kill rodents, but sometimes with the deliberate intent of poisoning cats (yes, despite the generally good treatment of cats in Indonesia, there are still cruel people who seek to harm them). To protect their kitties, the AFJ volunteers constructed a fence around the property with an inward-curving lip… very much like the solution employed at the Animal People office to keep our own cats from roaming out into the forest.

- Fencing with curved lip

- Fencing with curved lip

The inward-curving fence reduced, but did not entirely solve the problem, as some cats were still able to brachiate over the lip and escape. I told Ina, Nana, and Yani about Animal People’s similar fence, and how after years of struggling against the same issue, we had eventually thought to install plastic panels hanging downward from the fence lip, as an additional barrier against brachiating cats. Since this last modification, we had only had a single cat out of some two dozen still agile enough to escape. Ours was probably more expensive than AFJ can afford, but with some creativity I expect a lower-cost version could be improvised.

Later we would rejoin Nana and Yani for late-night cat feeding, but first Ina took me to another vegetarian restaurant, Fortunate Coffee, for dinner. I ordered a burrito, which turned out not to be very burrito-like – more of a culturally generic vegetable wrap – but was nonetheless very tasty, along with a side of tomato soup. Ina ordered an Indonesian noodle dish and salad.

- Dinner spread

- “Burrito” with fries

- Noodle dish and side soup

- Salad

- Cafe menu

- Inspirational words on the wall

Ina explained to me that the restaurant is run by the Indonesian Vegetarian Society and Vegan Society of Indonesia. Both Buddhist-affiliated, these groups’ vegetarianism is based primarily in religious teachings, but in recent years they have become increasingly interested in promoting animal welfare, and have partnered with Animal Friends Jogja in several campaigns. Before we left, we each got vegan personal pizzas to take with us.

Outside the restaurant, I caught a few blurry photographs of a horse pulling a carriage as he trotted past. Many more carriage horses were seen later on the way to feeding cats, though I was unable to get any decent photographs.

- Horse with carriage

- Horse with carriage

- Horse with carriage

I was reminded of a conversation with Femke the previous day, in which she summarized JAAN’s carriage horse welfare campaign attempted in Jakarta some years previously. Carriage horses in Jakarta, as in Yogyakarta and all over the world, suffer greatly from abuse and neglect: severely overworked, underfed and underwatered, often beaten, subjected to ineffective (and often painful and counterproductive) folk remedies for their ailments, and – once they become too exhausted to keep working – disposed of and replaced rather than retired to a life of dignity.

JAAN’s campaign was designed to be multi-pronged, addressing both the immediate welfare needs of carriage horses and the long-term goal of ending their exploitation altogether. For the former, JAAN set up a centralized location where carriage drivers could bring their horses to rest and receive medical treatment. For the latter, JAAN worked with local governments to ban the use of carriage horses one city district at a time. Unfortunately, the comprehensive nature of the campaign eventually proved its downfall, as carriage drivers discovered its long-term agenda and, feeling betrayed, stopped bringing their horses to JAAN’s center. Now, JAAN works exclusively toward an outright ban on carriage horses city-wide, having lost their keepers’ trust and so no longer able to alleviate their suffering incrementally. The campaign’s difficulties illustrate perfectly a universal tension in the animal cause, between the pursuit of animal rights ideals and the pragmatic need to improve animal welfare in the here and now, one that continues to vex activists worldwide.

Ina and I regrouped with Nana and Yani in a back alley near Yogyakarta’s main tourism district, to feed a small colony of street cats living there, as is AFJ’s routine every night. When we first arrived, the cats were rummaging through a pile of trash for scraps to scavenge. They were clearly grateful to receive a hearty meal of kibble and fish with rice. All of the regulars had already been spayed and neutered, but that night a new cat appeared, whom Ina followed and eventually managed to capture in a portable kennel along with two kittens. Over the course of several hours, we traveled to four additional sites in the same general area, each with its own local cat colony.

- Back alley

- Cats scavenging garbage

- Cats scavenging garbage

- Cats scavenging garbage

- Cats scavenging garbage

- Cats scavenging garbage

- Ina petting cats

- Preparing food for cats

- Preparing food for cats

- Cats eating kibble

- Street cat

- Cats eating kibble

- Cat looking up

- Street cat

- Cats eating

- Cat sitting on motorcycle

- Newcomer mother cat and kittens in kennel

- Mother and kittens in kibble

- Feeding cats at a different location

- Ina and Nana

- Cat eating

- Cat looking slightly grumpy

- Yet another location

- Cats eating

- Feeding cats, w/rickshaw drivers sleeping in vehicles

- Ina holding a local variety of catnip, which she used to calm mother and kittens in kennel

- Giving catnip to mother and kittens

The slums and back alleys were also inhabited by a large number of people living on the street. According to Ina most were not actually homeless per se, but their houses were located in faraway villages with few employment opportunities, so to make money for their families they spent long periods of time in the city, living as cheaply as possible while earning money from odd jobs to send back home. Some had gigs as rickshaw drivers or parking valets, though many others were waste pickers. While they did at least have homes and were fortunate to make an income, I nonetheless felt sorry for them, living in such squalid, unsafe conditions far from the loved ones they worked hard to support.

Their attitudes toward animals varied somewhat. One group lived in a rickety makeshift structure alongside the back alley we visited first, and did not like the street cats, shouting at us to be quiet and go away instead of feeding them (and shortly thereafter started playing loud rock music on a radio themselves). In general, though, the local people seemed to care about the cats. We spoke for some time to a woman who fed the cats her own food scraps and kept track of their numbers, and at another location were met by a group of concerned people living on the street who were worried we might be trying to poison the cats.

- Kind woman living on streets, earning odd jobs far from home

- Woman helping feed cats with Nana and Yani

- Locals concerned as to our motives

The night closed with a group selfie, evidently a tradition for Animal Friends Jogja.

It was close to midnight when we finally returned to Omah Jegok. It had been a very long and tiring day – from ancient Buddhist and Hindu temples, to wildlife black markets, to AFJ’s cat shelter, to late-night cat feeding in the slums of Yogyakarta – but a rich and rewarding one as well.

Day Eight: Thursday, October 1st

After returning to Ina’s homestay so late the previous night, I was fortunately able to sleep in a little. Femke had left the previous day, while I was visiting Borobudur and Prambanan, so I was now the only visitor. For breakfast I ate the vegan pizza I had brought home from Fortunate Coffee, checked the Forum and answered some e-mails, then accompanied Ina for another look at the Animal Friends Jogja shelter. This time Ina took me into the main kennel area, which I had only seen from the outside previously, but where most of AFJ’s dogs were kept. They came from a variety of situations. Some were street dogs or abandoned pets. One group had been surrendered by a man who loved them, but was superstitious about spay/neuter and wouldn’t let AFJ sterilize or take any of them until he eventually lost his apartment and had nowhere else to rehome them. A few had been rescued from dog meat traffickers. The kennel area was divided between a large common area, where dogs who played well with others were allowed to run freely, and a number of side kennels where those too aggressive, or who had not yet been vetted, were kept.

- Ina and retriever

- Dogs in separate enclosure

- Doggie

- One big dog family, surrendered by a man who had previously refused to sterilize them

- Dog family

- Dog family

- Friendly rottweiler, though not yet approved to run in common area

- Dogs rescued from dog meat traffickers

- Dogs

- Dogs

- Retriever and rottweiler in common area

- Pit bull in separate enclosure

My flight out of Yogyakarta, to the city of Balikpapan in Borneo, was that evening, and my taxi to the airport was scheduled for 5:00. I had just enough time left in the afternoon for Ina to show me some of the bizarre art produced by the land’s owners, then head to a quick lunch at Milas with Monique van der Harst, Animal Friends Jogja’s other co-founder.

- Faceless humanoids emerging from flowers (?)

- Indonesian politicians depicted as snails…

- …moving slowly, slowly…

- Snail politicians

- Human-faced tortoise

- Men carrying a trussed-up boar…

- …and the artist himself, depicted similarly trussed. Identifying himself with the boar’s suffering? Some sort of political metaphor?

- Another statue of a trussed boar, this time without a human counterpart

Monique van der Harst oversaw AFJ’s humane education programs, and was currently preparing for a program at Milas itself, which doubled as a classroom for a local school. She was also most closely involved with the organization’s anti-dog meat campaigns. I asked her a question that often comes up in activist discussions of the dog and cat meat trade: does focusing specifically on the consumption of those two species distract from campaigning against meat-eating in general, reinforcing an artificial (largely Western) distinction between companion and food animals? She replied that, at least for AFJ, she didn’t believe it did. For one, Indonesia’s dog meat trade does differ in key aspects from the meat industry in general, involving unique issues such as the theft of pets to supply the trade and its role in spreading rabies, making it a menace to public health. For another, she and Ina, the co-founders of Animal Friends Jogja, are both vegan, and the organization openly advocates for vegetarianism and veganism through events like Raging Green. I was satisfied with her answer, and agreed with her that there was nothing hypocritical or misguided about AFJ’s “Dogs Are Not Food” campaign.

As Ina had explained to me, the dog meat trade in Yogyakarta is largely hidden from public view, with the actual slaughter performed in hidden locations and the meat sold within the city already butchered and packaged. As such, simply educating people as to the reality of how dog meat is produced works well as a campaign tactic. However, in some parts of Indonesia, such as Sulawesi, dogs are sold live in public markets and brutally slaughtered in full view of customers, meaning that dog eaters in those regions are already fully desensitized to the animals’ suffering. How, I asked Monique, would she campaign against dog meat in a place like Sulawesi? She thought about my question, then answered that she would start by determining whether dog-eating was a local tradition or had been introduced from elsewhere. Since dog eaters (and animal abusers worldwide) often try to defend their actions by claiming them as cultural heritage, if it could be demonstrated that Sulawesi’s dog meat trade wasn’t actually a longstanding part of the local culture, that by itself would help to undermine its practice. Of course, extensive research would need to be done before actually attempting such a cultural argument against dog-eating. It seems to me that trying to reach out to young children, who haven’t yet been desensitized and are typically better at guilt-tripping their parents than anyone else, could also be an effective strategy in Sulawesi. Fortunately, working with children is something the educators and puppeteers of Animal Friends Jogja already excel at.

Lunch ended with another traditional AFJ selfie, and then I made my way to the airport and onward to Balikpapan, Borneo.

- Monique van der Harst

- Selfie! Me, Ina, and Monique.

Arriving in Balikpapan, I was surprised to discover an airport far more opulent than any other I had seen in Indonesia. Quite large, with sleek modern architecture, and spotlessly clean, it looked more like a major American or Japanese airport than one in the developing world, let alone what I’d expect in a place like Borneo, which I’d always imagined as mostly isolated wilderness. Furthermore, it had apparently just been completed, replacing another, equally fancy airport that had burned down shortly after its construction. I would later learn that Borneo is actually one of the wealthiest parts of Indonesia, thanks to large deposits of oil that can be extracted and sold abroad. As in most places, however, the majority of wealth never trickles down to the common people. Indeed, despite the Balikpapan government having enough money to build two palatial airports back-to-back, the general standard of living seemed no higher than in other Indonesian cities, save for the fact that it was far cleaner, thanks to uniformed government workers tasked with removing litter.

- Balikpapan airport

- Tropical garden in middle of baggage claim

- Orangutans are evidently a source of regional pride for Balikpapan

I spent the night at a hotel several blocks from the airport. The next morning, I would travel to Samboja Lestari, a reforestation and orangutan rehabilitation project run by Borneo Orangutan Survival Australia about an hour outside the city. There my expectations of Borneo would further erode, as I learned firsthand how perilous is the future of the island’s remaining forests and wild animals.

To learn what I saw in Samboja Lestari, and what you can do to save Borneo’s wilderness from total destruction, read Red Cups & Scorched Earth: A Better Reason to Boycott Starbucks.

The final entry in the “Archipelago Animal Adventures” series, my review of the 2015 Asia for Animals conference, will be published shortly.