Animal lover though I was, I was definitely not looking for a pet. I was busy training to be a psychologist. Then came Sammy – a mischievous and extremely loud bright pink Moluccan cockatoo who had been abandoned. It was love at first sight. But Sammy needed a companion. Enter Mango, lover of humans (“Hewwo”), inveterate thief of precious objects. Realizing that there were many parrots in need of new homes, I eventually founded a sanctuary for them.

Meanwhile, I began to meet homeless veterans on the streets of Los Angeles. Before long I was a full time advocate for these former service members, who were often suffering from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and finding it hard to navigate the large VA Healthcare System. Ultimately, I created a program for them too.

Eventually the two parts of my life came together when I founded Serenity Park, a unique sanctuary on the grounds of the Greater Los Angeles Veterans Administration Healthcare Center. I had noticed that the veterans I treated as a clinical psychologist and the parrots I had taken in as a rescuer quickly formed bonds. Men and women who had been silent in therapy would share their stories and their feelings more easily with animals. Now wounded warriors and wounded parrots find a path of healing together.

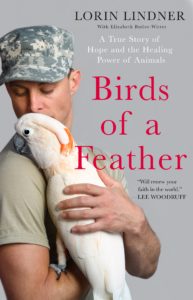

My new book, Birds of a Feather, is ultimately a love story between veterans and the birds they nurse back to health. Birds of a Feather is due to be released May 15, 2018 from St. Martin’s Press.

EXCERPT:

A Promise Is Made

On Christmas Eve in 1987, a bird’s screams echoed through the canyons of the Beverly Hills neighborhood of Trousdale Estates. The sound was a high-pitched, warbling wail, like a woman in agony, and it went on for hours. In the bird’s native land, 8,200 miles away, the cry would enable wild parrots to alert each other through dense rainforest to predators circling in the sky or crouching in the trees. In Trousdale Estates, a neighborhood full of multi-million-dollar homes carefully arranged on the hillsides, the sound reverberated through the otherwise peaceful and empty streets. This was the kind of place where celebrities and millionaires enjoyed the views of Los Angeles from their private pools, not where wild animals screamed for hours.

Neighbors called the police and animal rescue groups.

Animal Control contacted a friend of mine who worked with one of the animal rescue groups. She said she needed to find a foster home quickly, and she knew I loved birds.

“Do you think you can take in a parrot?” she asked. “If we don’t move right away, Animal Control will take it. We need help tonight.”

I was in the middle of studying for the Psychology Licensing Exam. Our professors warned us not to take on any additional responsibilities, and they told dire stories about low pass rates. This wasn’t the time for weddings, pregnancies, or new jobs. It was Christmas Eve, though. Everyone else was going to take a break. I could help, I thought.

“I’ll keep it until we can find it a good home,” I said.

When we arrived that evening, Animal Control officers escorted us into the mansion. It was for sale, unfurnished, and our footsteps echoed through the empty rooms. The house spread out from an airy central atrium. The walls were painted a light peach, and tall potted palms decorated the space. In a cage at the center of the atrium was a single Moluccan cockatoo. Nearly two feet long, she had pink feathers, and when she raised her crest, it was a rich salmon color. Her colors complemented the cool pastels and whites of the home. The owners thought the bird’s beauty would help them sell the house quickly.

For the bird, there was nothing beautiful about the space. There were no toys, no mirror or bell, nothing to stimulate and entertain her. No fruit or vegetables to pique her interest. No voices, bird or human, to comfort her. She was utterly alone. Her droppings had piled up like a pyramid to perch level.

Her cage had several locks, and she’d managed to open most of them. She couldn’t get out, but I could see there was an intelligent mind trapped in that cage.

My heart quickened when I saw the seed bowl full of empty hulls. I examined her keel, the breastbone that typically gets fattened up in chickens, and saw the sharp bone protruding from her chest. She didn’t have an ounce of fat. When Animal Control contacted the owners, they claimed they were sending their chauffeur about once a week to replenish her seed bowl. It is tragically easy to starve a parrot to death, because they eat only the insides of seeds, leaving the nutritionally valueless hulls behind. To the untrained eye, such as that of a chauffeur hired to drive a car, it can appear as though the seed bowl is still full when only empty hulls remain.

I’d seen people make this mistake before with parrots. One woman told me she had asked her children to feed her bird while she was away. She called daily to remind them to check his food. “Don’t worry. His bowl is full!” the children told her. That bird died an appalling death, even with people to care for him. Now I was seeing another animal who had been abandoned and starved, even while surrounded by vast wealth.

I looked from her keel to her eyes. There was fear there; she didn’t understand that we were there to help. There was also hope. Maybe, at last, someone had come to keep her company and rescue her. Mostly, though, I saw pain. I felt as if I were looking directly into a tortured soul. Those eyes seemed to be crying out to me.

I can’t explain it. I felt an immediate bond with this bird. I knew then that this rescue was going to take more than a few hours.

“I promise,” I said, “to find you a good home. I promise to make you happy.”

But what makes a parrot happy? Far too few pet owners know the answer to that question. Owning a bird is seductive, but people often don’t consider the difficulties of keeping an exotic animal. They want to care for and love a beautiful creature, but unless they understand the commitment involved, they can end up doing more harm than good. I knew the damage humans could inflict, but still, I could relate to wanting a bird. I always enjoyed being in their presence, but I had vowed years ago not to be a part of the animal trade. Here, though, was an animal not in a pet shop but left alone in a house for sale, because she complemented the decor. Here was an animal who needed me.

I realized I needed to learn what it would take to do right by this bird. She had never asked to be brought to this hemisphere, this continent. She had not asked to be isolated in a human world. I promised her she would have a permanent home.

I took her in. I gave her a human name, Sammy, short for Salmon, in honor of her beautiful salmon-colored crest. I had to learn how to provide the care she needed. And what I discovered ended up helping many others, parrot and human alike. Though I had no way of knowing it at the time, Sammy would lead me to a career of helping veterans find their way to healing. She wouldn’t be a distraction from my Psychology Licensing Exam; she would utterly change my views about my profession. And, perhaps most of all, Sammy would help me find my way to a life of love and service.

* * *

I wanted to understand where this bird had come from. I felt that if I knew her history, I’d know better how to care for her now. So I researched Sammy’s roots. I wasn’t there when Sammy was a baby, but I can imagine her early life because it’s the story of millions of birds wrenched from their homes in the wild.

With a likely birth year of 1977, based on the date of her importation, Sammy was wild-caught as a fledgling in the Moluccas, a mountainous Indonesian archipelago made up of over a thousand islands.

When hunters take parrots from the wild, the first step is often securing a fledgling to a tree branch, either with rope or, to make the cries even louder, with nails. The tiny bird’s distress call can be heard for miles around, drawing in her flockmates. The hunters count on the flock gathering together in one place, making the parrots easier to capture.

Hunters and poachers commonly cut down trees with nests, blighting the forest.

Over 50 percent of birds caught in the wild will die during either their capture or transport to market. Dead birds are an acceptable cost of doing business.

As in many exchanges between the West and the developing world, wealthy countries benefit far more from the trade than poor ones. Local areas suffer deforestation and loss of native species. A small fraction of the money made from the trade goes to the locals; most ends up in the hands of westerners. Once the trees and wildlife are gone, the locals no longer have a source of income….

The captured birds are kept in tiny cages in the marketplaces of cities such as Ambon and Jakarta. Conditions vary, but it’s not unusual for the birds to be left in unshaded boxes without food or water. The cages are rarely cleaned, leading to the spread of disease among birds already weakened by the rigors of capture and transport.

To keep the birds quiet during shipment—typically to the United States and Europe—smugglers use drugs and/or restraints….Crammed into poorly ventilated suitcases or stuffed into pipes to keep them hidden, innumerable birds die during shipment. They succumb to heat, crowding, hunger, and lack of air. They also die from the vodka forced down their throats to keep them sedated or from the curare intended to keep them immobile….Locals were aware of the effects of habitat loss and deforestation, and they often thought they’d be helping the birds by sending them away.

One great hope for the future of wild birds is that these very same poachers, those people who are trying to make a living to support their families, are now being taught how to use their skills to create an ecotourism industry in their native lands. Former poachers are now becoming experts on parrot behavior. Organizations like the Indonesian Parrot Project, Wild Planet Adventures, and the World Parrot Trust are helping local people build an economy based on protecting their native wildlife instead of capturing and selling it. Now, instead of climbing trees to poach parrot nests, native people are climbing them to build blinds and pulley systems to hoist tourists high into the tree canopy to see the species endemic to those areas. Maybe such a program could have saved Sammy.

Of the 30 to 60 million parrots in captivity (no one knows the exact number), very few find their way to a forever home. I have met many dedicated, loving people capable of providing a comfortable life for the parrots in their care. They number in the hundreds, and I’m certain there are thousands more, but are there millions? Untrained bird owners usually mean well, but many aren’t prepared for the work and attention they must devote to their pets. Parrots aren’t domesticated animals, so being neat, tidy, and quiet isn’t in their nature. As flock animals, they need companionship—more companionship than busy families can usually give.

Even if parrots find satisfactory homes, those homes are rarely permanent. Once people discover what owning a parrot entails, they often pass their bird on to another owner. In addition, people’s lives change, and sometimes they may no longer be able to adequately care for their birds, or their birds might outlive them. Longevity is species-dependent, but can be as much as sixty to ninety years in some species, like cockatoos.

We don’t treat other domestic animals in the same way. We would never expect dogs or cats to have ten to twenty homes in their lifetimes. One thing that invariably can bring people to tears—I know I cry when I hear such stories—is when an older dog or cat is dumped at the shelter after living all his life with one family. “He’s making a mess too often in the house now,” the owners say, and the shelter worker nods with coached sympathy. The dog’s eyes are full of dissipating hope and mounting fear as the family retreats to its car. I have worked alongside many of these shelter personnel while doing rescue work, and they have told me they long to cry out, “He is part of your family. What are you thinking?” Tens of thousands of elderly companion animals are destroyed each year at shelters after their humans abandon them.

Unlike those elderly dogs, who usually lose their families only once, parrots, with their long life spans, may experience this wrenching move multiple times. People aren’t as familiar with birds; they just don’t understand them in the same way they understand dogs and cats. After all, we’ve been living with dogs and cats for thousands of years. Many dogs have been bred to be perpetual puppies, needy and loving, with wagging tails. We breed out the assertive, aggressive behaviors as much as possible. Even domestic cats, seemingly more independent, have smaller brains and fewer aggressive behaviors than their wild cousins.

Parrots have agency and act autonomously. Their motivation is to please themselves, not us. Parrots forage for food and discard it on the ground, heedless of carpets and mess. They build elaborate nests (if no other suitable materials are available, they’ll destroy the furniture to do so). They call out and stretch their wings in elaborate courtship rituals. Their behaviors may be fascinating to study, but they’re foreign to us, and often annoy the people the birds live with. When parrots are rehomed, most people don’t cry; they think someone is just passing on a loud, annoying creature.

Sammy was a survivor. She made it through the capture process. She made it through the long journey across the Pacific. She made it through quarantine. If her flock had twenty birds, it’s likely five to seven survived. Whether it was because she was young, had a greater determination to live, or was genetically stronger, somehow, against the odds, she made it. She wouldn’t be so lucky when it came to finding a forever home.

REVIEWS:

“Dr. Lindner’s book reminds us of the extraordinary ways caring people are helping the men and women who have served our country…and animals along with them.” —Maxine Waters

“Lindner’s book poignantly entwines three narratives: Stories of humans ravaged by their experiences of war, stories of parrots (and later canids) ravaged by maltreatment, and her own story—how she finds a way to help these humans and nonhumans simultaneously and synergistically.” —Irene M. Pepperberg, PhD; Research Associate, Harvard University, author of New York Times bestseller Alex & Me

“An extraordinary story…Dr. Lorin Lindner’s writing radiates with warmth and love for humans and animals alike.” —Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson, Ph.D., The New York Times bestselling author of When Elephants Weep

“I wish this book had been available to me when I was first trying to learn the ways of parrots. My life was likewise turned around by the birds, who ended up getting me off the street. Birds of a Feather is both well written and engaging…” —Mark Bittner, author of the New York Times bestseller The Wild Parrots of Telegraph Hill

“This heartfelt book demonstrates that kindness to animals is also good for people, and that caring for others helps to heal ourselves. I greatly admire Dr. Lindner’s work, which helps both people and other animals by encouraging empathy and compassion.” —Gene Baur, cofounder and president of Farm Sanctuary and author of Farm Sanctuary and Living the Farm Sanctuary Life

“Through the tears of sadness, and hope I congratulate Lorin Lindner on her wonderful writing about the Birds of a Feather.” —Tippi Hedren, President, The Roar Foundation, The Shambala Preserve