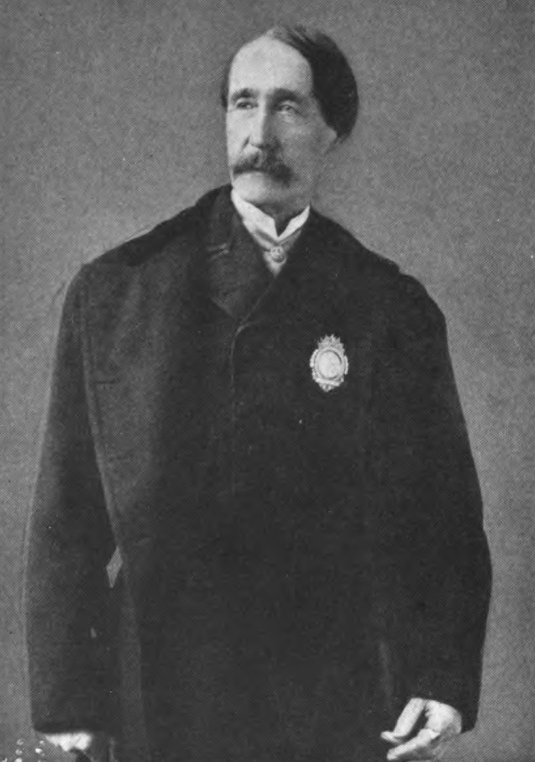

Any social movement benefits from knowing its history, and the animal welfare movement is no different. How did the modern movement to protect animals from cruelty begin, and who were the early activists who helped create it? One man who is credited with the genesis of the animal welfare movement in the United States is Henry Bergh. Bergh was the founder of the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, the leader of many campaigns in Gilded Age New York, and undoubtedly left his mark on today’s animal activism.

In a conversation with Ernest Freeberg, historian and author of A Traitor to His Species: Henry Bergh and the Birth of the Animal Rights Movement, we discussed Bergh’s work to help animals, his legacy, and what he might think of the progress we’ve made since his time.

Dylan Forest: Why did you want to write a biography about Henry Bergh? What about his story inspired your interest?

Ernest Freeberg: Our modern industrial cities were born the late 19th century. Among the many things we have inherited from that moment is a profound change in our relationship to animals of all kinds. In those years after the Civil War, humans and animals lived entangled lives. The city was an earthy but often brutal place for all those animals who provided the food, energy, and entertainment for a surging mass of people.

In the midst of all this, Americans began for the first time to organize to protect animals from the worst human abuses. Why did this happen when it did? One interesting way to answer that question is to follow the career of Henry Bergh, who founded the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) in 1866, and devoted twenty years to building the animal welfare movement.

Bergh could be considered an unlikely person to take on the issue of animal cruelty, as a wealthy socialite who came to the cause in his fifties. Did any formative events spark his interest in stopping animal cruelty, and what about this issue was so important to him?

Henry Bergh was a fascinating man, both inspiring and perplexing—even to many of his admirers. One called him “The Riddle of the 19th-Century” because he did not seem to particularly love animals. He had no pets, for example. Certainly he felt deep sympathy for abused animals, but seemed motivated mostly by a determination to stamp out human cruelty.

Since his intense crusade against cruelty seemed so surprising in his day, he was often asked how he got into the work. He told the story of his time in St. Petersburg, where Lincoln had appointed him to work in the US embassy. The Russian teamsters were notoriously abusive to their horses, and one day Bergh snapped at a man who was whipping his horse. Since Bergh was in an official uniform, the man quailed and dropped his whip. Bergh said that this single act inspired him. Until that point he had spent decades as a wealthy dilettante, a failed playwright who spent most of his adult life touring the capitals of Europe. Now he’d found his calling—brutal, hard work in many ways, but meaningful.

Bergh’s activism wasn’t always well-received by others, just as animal rights activism isn’t today. The book’s title, A Traitor to his Species, is a nod to this fact. Was animal protection a shocking concept then, and did Bergh have supporters as well as detractors?

Bergh passed the nation’s first state law against cruelty to animals of all kinds, and supported by badge-wearing agents of the ASPCA, went into the streets and slaughterhouses to make sure it was enforced. While many applauded the movement’s basic goal—after all, who comes out in favor of cruelty?—they often thought he went too far. Most thought Bergh’s aim was to protect the city’s many horses from the evident abuse they experienced on the streets of New York. Bergh did that, but also used the law to stop dogfights and pigeon-shooting contests, the exploitation of P.T. Barnum’s circus animals, the horrendous methods of controlling stray dogs, and even the abuse of turtles, bound for the soup pot in many of the city’s saloons. Many mocked him for what looked like excessive sympathy, fretting over animals that most thought could not suffer much, and certainly had no right to the law’s protection. And when Bergh began to take animal-abusers to court, people thought he was not just a meddler interfering where he was not wanted, but a tyrant who was imposing his maudlin sentimentality on others through the threat of arrests and fines.

But many, many others praised Bergh, claiming he was raising public awareness of these abuses, and making society less cruel. He might seem eccentric and a bit too energetic in his war on cruelty, but they admired him as a pioneer of social progress. In fact, Bergh’s ASPCA in New York was very quickly followed by similar organizations in Boston and Philadelphia, modeled on Bergh’s plan—and by the end of his career, most states had adopted similar laws, and thousands of women and men joined their local chapters of the SPCA.

Bergh worked for better conditions for a variety of animals. What were some of his biggest successes?

There were so many. He waged a colorful campaign to stop dogfighting and cockfighting, and experimented with more humane forms of animal control. Others in the movement, especially Caroline Earle White in Philadelphia, pioneered the first animal shelters, and experimented with more humane forms of euthanasia. The societies built water fountains for thirsty horses, and Bergh invented the horse ambulance. Nowhere was the movement entirely successful in stamping out abuse, but perhaps its greatest success came in provoking a national debate over animal cruelty in all its forms. Many of our own moral and legal quandaries can be traced back to the controversial test cases that he provoked more than a century ago. He gave his fellow citizens a language and a forum for talking about our obligations to our fellow species.

I’m curious about how Bergh thought about farmed animals before the modern vegan movement existed. Was he critical of meat eating at all, and were farmed animals among those he fought for?

In the late 19th century, livestock was shipped by rail, across thousands of miles, from the Texas plains to Eastern urban markets. That trip was brutal; no food and water for days, and no regulations on how many animals could be crammed into a boxcar. Many animals died on the journey, a loss that was just considered an inevitable part of doing business. Bergh and his SPCA allies in other states organized to pass the first federal law that required better treatment for livestock on the way to market. Bergh used an argument that rings familiar today: that abusing the animals we eat is not only immoral, but also unhealthy, likely to produce diseased meat that will make us sick.

Bergh also worked to make the slaughtering process more humane, with limited success. In spite of all the disturbing scenes he witnessed in these rail yards and slaughterhouses, he still ate meat. He said more than once that he expected one day long in the future, as civilization progressed morally, people would become vegetarians, but it was a step too far in his time. I think he recognized, as well, that pushing for a vegetarian diet would have only led to more ridicule of the movement, undermining public support for the good work he was accomplishing.

How can we see Henry Bergh’s influence in the modern animal rights / animal protection movements? Are there elements of how these movements work today that are part of his legacy?

In his day, standing up for animals was mocked by many, praised by many more, and was often called by journalists an expression of “Berghism.” But Bergh was not a lone eccentric, but one of the founders of a wide social reform movement. His efforts would have come to nothing if not for the law that gave SPCA branches power to act, and they in turn relied on the active support of thousands of men and women across the country who joined, raised funds, and otherwise supported the cause. They drew on some of the strategies of the recently successful anti-slavery movement—active lobbying of legislatures, the spread of literature to raise funds and consciousness, and organizing at the community level. The movement was particularly keen on cultivating sympathy among young people, promoting a “humane education” that might raise up a new generation of kinder men and women.

The title of the book calls Bergh’s activism part of “the birth of the animal rights movement.” Did Bergh use language about the rights of animals at the time, or was there some other way he articulated the reason animals should be protected from cruelty?

Today we often distinguish animal rights from animal welfare, and would think of Bergh as a champion of the latter—not making the stronger claim that other species are entitled to full rights as moral beings, but only that humans have an obligation to treat them as well as possible (while still claiming our own right to own and use them for our purposes). But Bergh did claim that animals had one essential right, the right not to suffer cruelty. Today that claim looks less controversial than it did when Bergh launched his movement, though we still struggle to realize that limited form of animal rights.

There have been huge advances for animals since Bergh’s time, but we also still have a long ways to go, and some issues may even be worse, such as factory farming and species extinction. If Bergh could visit us in 2020, what do you think he would think of the progress we’ve made for animals?

Bergh would be glad to see the many vibrant animal welfare organizations, the many people who are working on this issue, and would consider them to followers in his footsteps. But he would have to agree that the problems remain, even as the work of animal protection has expanded in directions he scarcely anticipated.

Take the case of factory farming. In Bergh’s day, before effective refrigeration, slaughter was done at the retail level, and each city had hundreds of small butchering operations, making the process all too visible to city dwellers who cared to look. And Bergh was horrified to find that many found watching this slaughter to be entertaining. He felt sure that the cruel treatment of these livestock that he saw there in New York was coarsening the souls of those who watched. So, he advocated the creation of large, centralized slaughterhouses, and applauded when the great Chicago meat entrepreneurs developed a way to mass produce and distribute refrigerated meat. Of course, this was a major step toward our factory farming system, a moral disaster that is much more hidden from public view, especially thanks to many “ag gag” laws.

And Bergh’s work in the Gilded Age was scarcely informed by the insights and concerns of the modern environmental movement. The SPCAs were essentially urban, where all could see evidence of abuse on the streets in front of them. Understanding the more vast systemic cruelty of environmental destruction and species extinction required a wider vantage point, a vocabulary of concern that was just emerging in the late 19th century. Bergh and his allies did protest the wanton slaughter of the bison, and the use of bird plumage in women’s fashion, but meaningful action on these issues came from other organizations, and too late in too many cases.

Featured image: horse-drawn carriages in New York City during Henry Bergh’s time. Creative commons image.