On 16 May (2019), the Sanger Institute outside Cambridge in the United Kingdom announced it would be closing its laboratory animal facility in the next few years. It came to this decision “following a rigorous review” of its scientific strategy and after consulting with the Wellcome Trust, one of the major funders of biomedical research in the world today and a very generous supporter of programs at the Sanger Institute. This is a momentous decision, but it is not particularly surprising (except for the timing – earlier than expected) to those of us who have been following the animal research issue over the past thirty years.

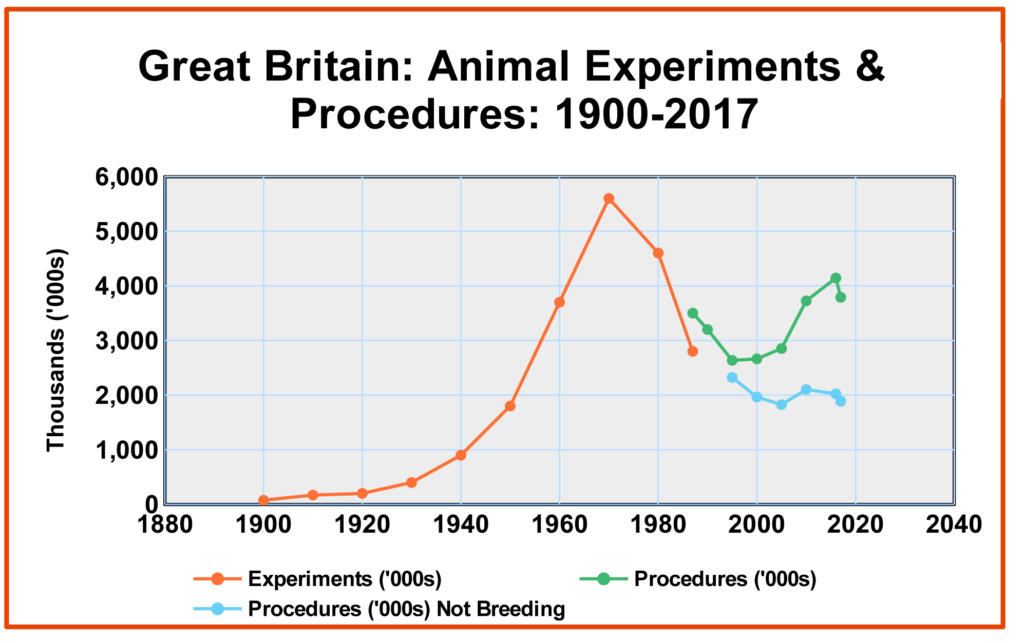

In 1987, the authorities in Britain switched from counting “experiments” to counting “procedures.” The main difference was that “procedures” now included breeding of animals for experimentation and the number of laboratory animals reported annually jumped by about 20%. However, in the mid-1990s, new genetic techniques allowed researchers to create “designer” mice with specific genetic properties and the creation of genetically modified mice took off. But the last year or two has seen a significant decline in the production of these “designer” mice, in part because of the development of new non-animal technologies and also in part because the “designer” mouse revolution has mostly not produced the breakthrough new therapies that were predicted.

In fact, the last two Directors of the National Institutes of Health have both noted the lack of success of the new mouse models developed using genetic engineering techniques and have called for the development of new approaches based mainly on the culture of human cells and organs (made possible in part by the development of new techniques in human stem cell culture).

A masked laboratory worker dispenses liquid to a mouse at the now-closed Coulston Foundation. Image credit Jo-Anne McArthur / We Animals.

The Sanger Institute (a key player in the sequencing of the Human Genome at the end of the 20th Century) is now positioning itself to continue to be a leader in biomedical research by embracing the very promising new non-animal technologies (such as stem cell techniques, human organs on a chip, mini brain techniques and, in toxicology, new high throughput cell culture approaches). We are beginning to see the prediction by Nobel Prize Winner Sir Peter Medawar come to fruition.

In 1969 (fifty years ago), he stated that, “… research on animals will provide us with the knowledge that will make it possible for us, one day, to dispense with the use of them [in the laboratory]altogether.” (The Hope of Progress, 1972, Methuen.) While people may argue that the Sanger Institute is jumping the gun on Medawar’s prediction, I argue that they have the timing just right!

In 2017, we saw the first tentative sign in the numbers reported by the UK Home Office that animal use in experiments is starting to go down again. The numbers for 2018 have just been published, affirming the reduction with a 7% drop in animal procedures from 2017 to 2018.

As the EU Directive in 2014 required a slight change in how animal procedures are reported, it is likely that the rise from 2014 to 2015 in the above figure was an artifact of that change and that animal use in Great Britain has been falling since it peaked in 2012/2013.

As the EU Directive in 2014 required a slight change in how animal procedures are reported, it is likely that the rise from 2014 to 2015 in the above figure was an artifact of that change and that animal use in Great Britain has been falling since it peaked in 2012/2013.

I expect this trend to continue and, perhaps by 2050, most of laboratory animal use will have been replaced by non-animal technologies, affirming Medawar’s prediction.

This article was originally published on the Wellbeing International website.

Featured image: macaques huddled together at a captive breeding facility in Laos, where they are bred to be sent to laboratories and universities around the world. Image credit Jo-Anne McArthur / We Animals.