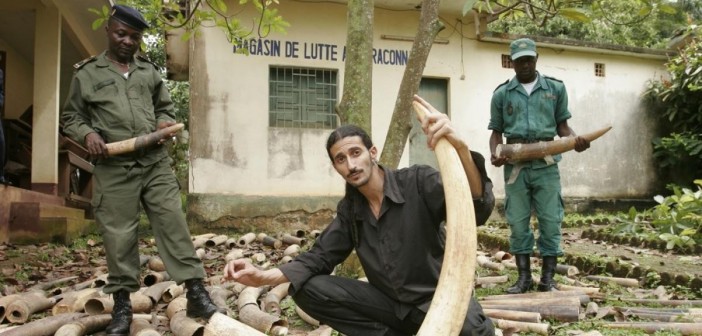

(Featured image: two tonnes of ivory seized in an operation in Cameroon, September 2009. Ofir Drori center. Copyright EAGLE Network, all rights reserved)

Video Transcript:

My name is Ofir, and I am the founder of the EAGLE Network. We are at the forefront of fighting wildlife crime in Africa. That isn’t the poachers, but the big traffickers. Our work is to hunt those traffickers down. We do this on a daily basis, which means almost every day we put someone like this behind bars.

I’d like to take you on a journey. My journey of how I got into this in the first place, my adventure, which is also my cause and also my fight, and try to reach out to you and try to connect with you. Because every time I speak, I get some more people that want to join us and participate in this fight.

When I was 18 years old, I went to Kenya, to the Kenya reserves. I took a backpack and started walking, and I got so fascinated by the wildlife and everything that I wandered out of the reserves and got completely lost. And these are the people who found me and saved me [shows photograph of seven African tribe members and self]. And so I lived with the tribes, and this is how I fell in love with Africa.

After my military service, I went back to Africa and I crossed thousands of kilometers through the wilderness, with my camel or on horseback or in a canoe or on foot. I did this because I wanted to live with the most remote tribes and try to learn from them their rich values and traditions that I think we in the West have long lost. This was very fascinating for me. So quite naturally I turned into an activist. I wanted to give back to the continent that gave me so much. From teaching in villages, to assisting in humanitarian operations, to writing on human rights violations from war zones in Africa.

And this is how I got to Cameroon, as a journalist, taking a break from writing about human rights, and the stoning of women in Nigeria. I needed a break, and I thought going to Cameroon and writing about the extinction of apes was something important and relatively easy to do. I went to Cameroon thinking of a sentence from primatologist Jane Goodall, who said that in twenty years, we’re going to lose great apes and gorillas forever because of the illegal trade in their meat. Basically the meat of gorillas and chimps is like the caviar of Africa. Somebody who wants to impress his friends will serve gorilla meat or chimp meat. It’s a status symbol and shows he’s very powerful, because it’s so rare to get.

[footage playing of wild gorillas and chimps]

Look at those magnificent creatures, see them playing, they’re just like us. I thought, this is a cause that’s worth my time to write about. And the idea was to direct the public to the good efforts of conservationists in those places fighting to save those species.

When I arrived in Cameroon, the consequences of the trade were pretty visible. What I saw was very organized trade in the meat. The slaughter was all over. And it wasn’t rooted in poverty or poor people, it was rooted in the rich and powerful. It was clear that those who were trading these animals were also the police officers and wildlife officers who were in charge of enforcing it. The crate you see here [footage playing in background] was used to transport six chimps at one time, and each of these chimps would fetch thousands and thousands of dollars for the trafficker.

There was already a law in Cameroon that gave up to three years imprisonment to anybody doing such things. So as a journalist looking at all these things, I asked the question, if that’s been the law for nine years, how many times was it applied? And the answer was one big zero. Zero wildlife law enforcement. That was a big failure, a very strong failure. And it wasn’t just in Cameroon. It was in all of central and west Africa. Everywhere you have forests, where these chimps and gorillas live, these countries never had a single wildlife prosecution at all. It seemed to me like a systematic issue, with some connection to corruption. But it wasn’t just a failure of African governments. It was also a failure of conservation.

I had most of my article ready: the extinction of apes, beautiful creatures so much like us, racing towards extinction because there’s illegal trade, and while there is a law it’s not applied because of corruption. That’s almost an article. But I was still looking for an ending, something positive, so I turned to the conservation NGOs. To the EU, to the World Bank, to the UN, those programs of conservation that claimed to save these creatures. But instead of answers, I found empires and huge castles and four-by-fours driving around. This was the answer I got: “Enforcement? That’s not us. We do workshops, we do seminars, we assist the government.” When I talked to them about corruption, they couldn’t even pronounce the word “corruption.” It’s not their business. “Don’t talk to us about corruption.” It seemed to me like they were ignoring their number one problem.

I was extremely frustrated by conservation. I was so frustrated by what I could see. And I really didn’t know what to do. So I had an unfinished article. All I could do was just get out and continue my research. And that led me to a small town where I could take a picture like this on the first day. [shows photograph of dead gorilla] And in this rural town, the people were very straightforward with me and said “Hey, look, we have ape meat sold here and gorilla hands sold there, and we also have two live ones.”

What they meant by two live ones were the orphans of the trade in ape meat. Basically, when a poacher comes and kills apes, he ends up killing a family of apes, because apes live in families. A mother carries her baby on her back for the first three years of his life, and he’s totally dependent on her. So the poacher kills a mother, and she falls down on the ground. The baby, still helpless, clings to the mother’s body. He doesn’t run from the poachers, he just clings and cries. So the poachers think “There’s not enough meat on this one. Maybe I can cut it and try to sell it for what it is, or maybe I can try my luck trying to sell it as a pet.”

In these situations, you have the orphans living on borrowed time before they die. And this is what I had in front of me, a baby chimp that was offered for sale. He was abused, and they treated him like a rat, and his emotional world was locked. Some of these babies are so sensitive, that even if you give them water and food they won’t survive for long, because what they need is love and attention. Gorilla babies especially, without love, even with water and food they just let themselves die. And they tried to sell this baby chimp to me for a hundred dollars, but of course I wouldn’t buy him, because if I gave them the money they’d just run back to the forest and capture some more, because there’s more demand.

I was extremely frustrated, so I went to the wildlife officers and I said, “Hey, there is this baby chimp, there is a law and it needs to be applied. Save this baby chimp, it’s a year and a half old. This baby chimp could outlive me.” But they just wanted bribes and were saying no, while I was going at them for half an hour saying do your work, it’s the law, it’s on the wall, it’s written. And after half an hour of arguing, they told me, “Hey, what’s your problem white man? You want a baby chimp, I’ll sell you another baby chimp.”

So the wildlife officers were selling to the traffickers! That’s something that was beyond me. I was so angry, and I couldn’t sleep that night. I went back to the hotel, and I had all this anger in me, against conservation and the big organizations and the African governments, and all of this was now in the face of this baby chimp. It was haunting me. I took a piece of paper and I started writing down all my anger, and I wrote an outline of what NGO I had expected to find, an NGO that would fight corruption to get the law applied, with activists trying to achieve something.

The following morning I went back there, back to this baby chimp, and I was determined to save it. I wanted to save this baby chimp. They had a big house, these traffickers, but they kept the baby chimp in a small kitchen outside. I went there and I took the book of law and I put it on the table and said, “Read this. Three years’ imprisonment.” And they read it, and looked at me, and read it again, and looked at me, and you know what? They were totally unimpressed.

But then I started bluffing them using what I wrote the night before. I said I was part of a new big NGO, with a big castle in the capital, lots of four-by-fours driving around, and our role was to fight corruption to get the law applied. My job was to prevent them from taking bribes. And you know what? Now they got hysterical. They started shouting at eachother, and I let them boil in their juices. I took out my phone and started talking as if to my imaginary headquarters, and said “Yes of course, they’re here, the judges are awaiting you.” Then they got really hysterical. After a while I told them, “You know what, if you remain my informants and tell me about the organized crime around you, and the bigger traffickers, then maybe there’s something I can do for you.”

At that point, they just wanted to get rid of this baby chimp. So I went there, and started untying this baby chimp from his ropes. The ropes around his waist were hurting him, and he had blood running down his sides. I untied him, and everyone thought he was going to run away. They had treated him like a rat and his emotional world was locked, and he was acting like a rat. He wanted to bite everything. So they were waiting for him to run away, but I just untied him and held up my arms, and he started climbing, climbing, climbing and gave me one big hug.

In that second, he transformed from a rat back into a baby, a baby with emotional needs. I named this baby Future, because that’s what I wanted to give him.

And so I found myself mother and father to a baby chimp, because he kind of adopted me. I didn’t choose it, but I was stuck. I was a journalist moving through a foreign country, and suddenly I was a mother and father. In my hand, I held an outline, the plan I had written that night, not just to do something for the future of this baby chimp, but something for the future of his species. Future forced me to stay and live up to the words I wrote that night and try to apply them. And that’s the story of the opening of the first wildlife law enforcement organization in Africa, LAGA, the Last Great Ape Organization. And now, years after, when we’re chasing far bigger criminals and putting them behind bars, the face of Future is still there reminding me why I do what I do.

So what is it? Basically the idea was to create a structure that would mostly fight corruption and have one measurable standard, a product. NGOs don’t act like companies, and that means many times they have no product, and they’re not tested. I wanted to have a product, and the idea was to take a country that had zero wildlife prosecutions through its entire existence, and move it to getting one major trafficker behind bars every week. The idea was to go after the big guns, not the poachers who are small and activated, but the people who activate those poachers. The government officials, the people who are wealthy and strong and many times work with impunity.

Now when we started all this, I was alone, I was just one guy, so I tried to get around me African people who would fight with me on this. We had nothing. We had no office, no car, no salaries, no money, no donations, no budget, nothing. Just an idea. We worked from cyber cafes and we met in bars. But that was great, because it means we acted on our activism, and our values, and our motivation was a strong internal motivation, not an external one. We had to foster activism.

We have four different activities under this model. We have undercover investigations, arrest operations, legal assistance, and the media.

The investigation department we have is basically undercover agents. They have hidden cameras and hidden recorders, and their role is to infiltrate the trade, and move up the chain to find the big guys and get evidence against them so we can arrest them. [footage plays] In this example we see a clothes shop, but with a hidden camera we found that this was just a cover for trade in leopard skins. You see the shopkeeper has just brought out the week’s merchandise, skins from seven leopards that were killed just for that. And now that we have this evidence, we are able to go for an operation and arrest these guys.

The next department is the operations department. That’s where we take the police officers and wildlife officers by the hand – and don’t get me wrong, it’s the same corrupt guys – and take them to a wildlife sting operation that we are planning. We are the ones handling it. In the sting operation the criminal will be arrested, and he won’t really know how he got arrested. Now, in 85% of all our arrest operations now, I can tell you who was trying to take a bribe. But I’m not just saying that, because we’re not the watchdog group, we’re not denouncing. We are fighters. So when we see bribery, interception is only one part of it. We fight it heads on using anti-corruption techniques in real time, and get this operation going and get these guys to the court. Fighting corruption is a big part of the operation.

[shows footage of sting operation]

Here is an operation involving elephant ivory, in which I was actually the investigator, and you can see them being arrested after they showed me the ivory, and going to the station to be interrogated and move through the court.

The next department is the legal department. You can see it never ends, it’s a full chain, and you have to go through the entire thing. So once they go to court, the court is also corrupt. What do you do? We formed a team of lawyers and advocates and we represent those cases for the state in the court, but more than anything we intercept corruption. So when the magistrate is trying to take a bribe, we know it. We know it because we put a recording machine inside his office, so we’re able not only to protect our case but to get him out of the judiciary altogether. In 80% of all of our cases, I can tell you who was trying to ask for a bribe, who was trying to get somebody out illegally. And again, we’re not just watching it, we are there to fight it heads on.

The last department is the media, because enforcement is not just about putting everyone in jail, it’s about deterrent. Deterrent means advertising and showing the public that now there is a risk. So every time there is an arrest, every time there is a prosecution, every time somebody goes to jail, it’s in the news. Seven months after we started, a group of activists with no money and no budget and nothing but an idea, we got the first ever prosecution and imprisonment of a wildlife trafficker in the history of central and west Africa. From that time on, we stabilized the country in exactly the way we wanted, what I wrote that night before I saved Future. That’s one major trafficker behind bars every week.

So that’s how it advanced from the very beginning. [shows footage] This is the first prosecution. This chimpanzee is Kita. She was traded and this guy went to jail. It was a historical case, and we managed to get more cases on ivory and leopard skins and lots of other important wildlife crimes. Once we got the first prosecutions, we were able now to climb higher, and get the big guys in the ivory trade. You see those chopsticks [made of ivory, in video] are for the Chinese market. We managed to climb higher and higher, and go after a police commissioner, an army captain, politicians, and put them in jail. We were able to go after foreign nationals. This is a Greek logging company owner, and he went to jail because he was trading wildlife.

We managed to go after the bigger politicians. You see here are some parrots. We were after a big racket of African grey parrots, a trade that is given a revenue of one million dollars per week. It was a huge pyramid in Cameroon, and we tried to find out who was on top of this pyramid making one million dollars per week. It was no one else than the deputy minister in charge of the environment, and we had to get him out.

We managed to get to the big criminal syndicates of ivory, the ones that are using big shipping containers. Inside one shipping container they can move 600 tusks at a time. That is 300 elephants killed. Imagine one family working for three decades, every two months taking the tusks of 300 killed elephants. We think that this one family was in charge of the killing of over 36,000 elephants. One crime family, employing dozens of corrupt colonels and generals and magistrates and mayors in six African countries stretching up to Asia, and hundreds of poachers. We are not after the small poachers, we are after guys like this.

So this is how things developed. Fast forward, and now we’ve replicated this model in eight countries, and united them under the EAGLE Network. EAGLE is all of these countries together, and we keep growing. More and more countries are in our network, doing this exact same thing. We have now more than 1,200 major traffickers that we’ve put behind bars, hitting corruption in higher levels. We get people like this guy, who is the chief, who was working for almost four decades and was in charge of the killing of more than 32,000 elephants. Or someone like this guy, who’s a drug trafficker. You can see here fifty kilograms of cocaine and marijuana [inside trunk of car shown in video], and there in the middle is a small diaper with a baby chimp inside. This chimp is worth more in revenue than everything else put together. We got this trafficker behind bars.

I wrote a book two and a half years ago, called The Last Great Ape. When I wrote it, I was overwhelmed by the responses I got from the public. There were so many people who wanted to join, who said,”Hey, I want to help, what can I do?” Some people came to Africa. Some people sat at the computer and did internet investigations for us, and others used different skills to assist us. Some gave money and helped us to expand to other countries.

I want to thank you for the opportunity of being here and being able to talk with you, and share some of our passion and our cause. I hope that some of you can join us and participate in the fight. Thank you very much.