Many of us know how incredibly difficult it can be when an animal you love dies. The grief over losing an animal companion can be just as painful and incapacitating as that over losing a human loved one, though we are often expected to move on much more quickly and easily. This attitude is just one symptom of a society that devalues animals and tells us that their lives (and deaths) don’t matter. On top of mourning the loss itself, many people are also left with the sense that others don’t understand their grief and few supports exist to help them.

Luckily, some experts exist who specialize in guiding people through the death of an animal. One such person is Reverend Kaleel Sakakeeny, who works as both an animal chaplain and a pet loss counselor. Sakakeeny brings his perspective on valuing animals and the human-animal bond both to faith-based communities and to individuals who are struggling to cope with a loss.

In an interview with Reverend Sakakeeny, we discussed his work, the power of the human-animal bond, and how he helps people move forward rather than move on.

Dylan Forest: You are an ordained animal chaplain and credentialed pet loss and bereavement counselor. How did you end up in such a specialized role, and why is this work important to you?

Reverend Kaleel Sakakeeny: It began with the death of my beloved cat, Kyro. He was truly a big love. When he died, the light went out of my life. I was lost. I drank too much, wandered around aimlessly, and developed depression and back pain. Clearly his loss and my grief triggered unmourned losses from my past. But still, I suddenly saw as I never did before the sacred power of the human-animal bond. I came to learn since then that a full 30% of mental health problems are the results of accumulated unmourned losses in our lives.

Kyro’s death crystalized what love, loss, grief and healing mean. I began serious studies in animal communication, which was a fascinating process. Then Reiki for animals, EFT with animals and so, one thing led to another. As the spiritual nature of grief and love became apparent to me, I was pulled to become ordained as an animal chaplain and pastor and become credentialed here in the United States and in the United Kingdom as a pet grief and bereavement counselor.

In truth the work is all about listening creatively and very, very carefully. Listening for the meaning behind the story. The story within the story. That’s how moving forward (not moving on!) works: reckonings, story telling, externalizing the grief. Animals are the angels of our better selves. They bring out the better parts of us. So when they leave us, there is a huge hole in our hearts. A darkness descends. My work is to hold the belief that grief is healing and deepening, and we will love again. The pain will soften. That’s the frame within which I work.

You offer one-on-one grief counseling to people who have lost a companion animal. What kind of resources or support do you find people most often need to cope with the death of an animal?

The most common challenge is to separate the guilt from the grief! Guilt always accompanies grief. Especially if euthanasia is involved. Did I wait too long, should I have had the operation, why didn’t I see the signs, and on and on. When we can untangle guilt from grief, we have clean pain, clean grief, and we can begin the healing process and truly be free to honor and remember our beloved animal companion. One’s loss story will get repeated over and over and over again. And I listen. Because the more the griever tells her story, the more control she gets over it. The more externalized it becomes and the grief journey can move forward more fully.

Often, we encounter the messaging that losing an animal should not really be that big of a deal, and those of us who grieve deeply or for a long time after the death of an animal are often treated as if we should be moving on much more easily. Do you encounter this idea often in your work? How do you respond to it?

Actually, the people I work with encounter it. It goes back to the concept of speciesism, which says that one species is more important than another. And thus one race is superior to another, one gender is superior to another, and so on. We have abandoned the spiritual oneness of our being by making these kinds of distinctions. The distinctions also play into the values of society, where we’re taught that animals are ours to eat, experiment on and to entertain us. So, if we eat them, why would we weep so deeply over them?

What lessons have you learned about the human-animal bond in the course of your work?

That, as the poet John O’Donahue said, “Animals know this world in ways we never will.”

I have learned that love is love and grief is grief, whether the loss of a pet, a job, health, friendship, a relationship, etc. We just don’t typically see all these losses as losses and honor the grief and need to mourn they can bring.

The loss of a pet, an animal companion, shakes us in ways the death of a person often doesn’t. So many times I’ve heard someone tell me that they didn’t grieve or cry as much at a parent’s death or a friend’s. Well, the animal-human connection is without some of the complexity of the human-human connection. There is no betrayal, no judgement, no animosity that lasts and lasts and is finally without reason. Yes, it may be a cliche, but the love shared between us and our animals is purer and more deeply honest. It touches some deep, better part of us. Not so with relationships between people, which can bring great beauty and kindness, but also terrible disappointment, hurt and criticisms.

This year, your organization Animal Talks was incorporated as a nonprofit. Can you tell me about the organization and what it does?

Our mission is to be present for those who love their animals and who have had to say goodbye, and are suffering the bone-marrow pain of the physical end of that relationship. I work with people in Berlin, Los Angeles, Colorado, London, Canada, and all over. Our second mission is to work for animal rights. Not animal welfare, animal rights. The true and perfect equality of humans and animals.

We’ve been lucky to see our work featured in People Magazine, Pet Gazette, The Boston Globe, and ABC/TV. We’ve published three e-books, I conduct a lot of Blessings of the Animals ceremonies in conjunction with faith leaders, and I give workshops and small-group lectures. Becoming a 501(c)(3) opened many new doors for us as well.

I’d love to know more specifically about your work bringing animal rights messaging to churches and other faith-based groups. What does this type of outreach consist of when you do it, and how has it been received so far?

Mostly it’s “educating” faith leaders on allowing and encouraging animal references, blessings, metaphors, reflections, artwork and stories into the service, the liturgy. The sermons become a sort of resource and conscience, a reminder that we are not the only species or the most significant one either. Who of us can run like a cheetah? Remember the sculptor Giacometti, who said that if he could save only one thing from the burning Louvre, it would be the caretaker’s cat. That’s my philosophical and spiritual foundation, the consciousness I try to bring into my religious messaging.

I develop good, solid relationships with local faith leaders, many of whom know that their congregations can benefit from other ways of looking at life, other dimensions of reality. Many people in any congregation have a pet they love, so in some sense, our talks and references are more emotionally connected to the people. Faith leaders will reach out to me to co-pastor a service on healing, knowing where I will take it, or to run the blessings of the animals in the field on St. Francis’ feast.

Nothing is formalized. I’m a “humane” resource and pastor for them. A colleague, a fellow pastor whose church just happens to be the environment and the animal kingdom, much more so than theirs is. And mostly they’re cool with that.

Finally, what would your message be to a reader who is struggling to cope with the loss of an animal?

Probably to let themselves feel what they are feeling. Let them dive deeply into their emotions and express them fully. Grief is not an event with a beginning and end. We never stop grieving. The hole in our hearts is forever. So please help me help you come to see that there is no return to normal or “the way things were.” Now we must build a relationship of memory and spirit. In the meantime give yourself grief breaks. Take care of yourself physically, like staying hydrated. Don’t make any major decisions, and know that these feelings are natural because there can be no pain without love. Grief and love are conjoined, and so the tears and sadness are testimonies to the deep love of your relationship. Don’t try to fix it. Let it be.

A broken heart is not a mental health issue, but seek help if you feel you are on shaky ground. Reach out to friends and family, those you trust, be loving of yourself, and know that death never ever ends the love or the relationship.

Rev. Sakakeeny and Animal Talks offer free grief support services to those who need them, as well as other services. Learn more at the Animal Talks website.

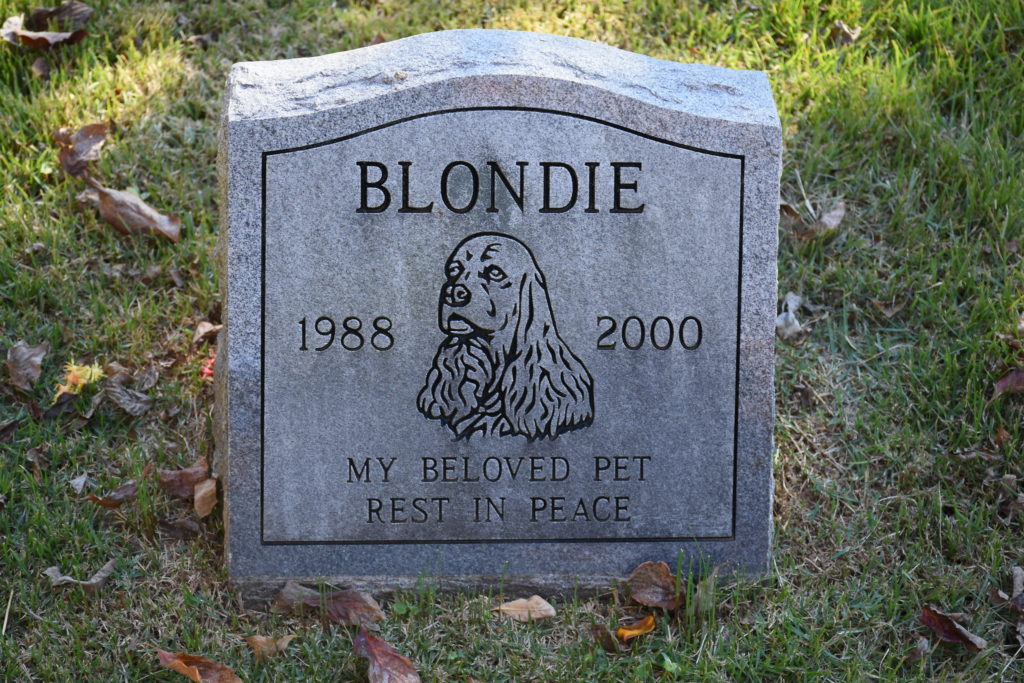

Featured image: grieving at a pet cemetery. Image credit Matt Baume, CC BY-SA 2.0.