Four baby elephants are about to begin an arduous journey of over 2,000 kilometers between the Indian states of Assam and Gujarat. Separated from their families, confined in cages and loaded on trucks, they will be bumped and jolted for days until they reach their destination at the Sri Jagannath Ji Temple in Ahmedabad.

Earlier this year, based on the heatwave conditions in Northwest India, the honorable High Court of Guwahati mercifully put this journey on hold. The temperature may have changed since then but the basic trauma of what these young elephants will be put through has not, nor have the bleak prospects of the lives for which they are destined.

This is illustrated by another elephant, very far removed in both age and location. Padmanabhan is one of the venerated temple elephants of the famed Guruvayoor Devaswom temple, part of a large Anakotta (elephant fort) of over 50 captive elephants in the temple compound. At the age of 80 years old, Padmanabhan has spent an entire human lifetime in captivity.

As per the recommended Kerala Captive Elephant Management Rules, temple elephants should be retired at 65 years old. Padmanabhan is 15 years past this age limit, but with the onset of the winter Pooram festival season, in breach of every government and Forest Department guideline, he was allegedly paraded through the crowds and chaos of the Ekadasi rituals on the 8th and 9th of December.

All animals are sentient beings with real feelings and emotions. Contrary to popular belief, just because animals cannot always express their pain in ways human beings can understand, that does not in any way mean that they cannot feel pain. For example, many animals’ sense of hearing is so strong that a noise that may not bother the average human being will be intolerably loud to them. Elephants are a cognitively advanced species who communicate in the wild through songs, by thumping on the ground, and by leaving and tracing smells across kilometers, all things that we humans cannot perceive.

Elephants also have very highly developed emotional intelligence, a deeply sensitive understanding of things and a very specific, inherent sense of self. They are highly complex social and sentient beings, and their experience of captivity is no less than a loss of free will, autonomy and freedom, comparable to humans.

Like humans, elephants need the support of families. Elephant herds contain well-defined social structures, and their interactions impact the growth and well-being of each elephant, just as living in a family shapes human lives. Captivity in any form is a denial of living free, in the wild, in a herd, which are core and essential elements of being an elephant. Once devoid of a sense of self, any creature would find themselves lost and rootless.

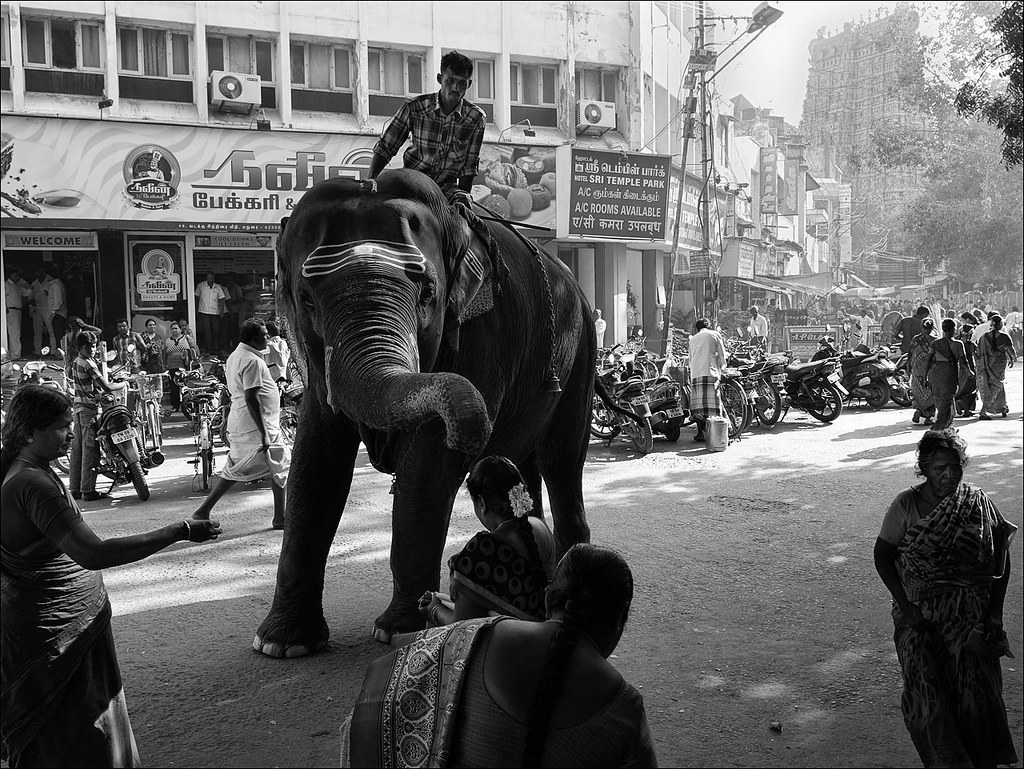

We recognize that elephants have a traditional religious significance in India, and that the wealthy devotees who “gift” them to temples like Guruvayoor might feel they are acting in a benevolent way. These gifts may especially seem positive compared to the even greater cruelties that elephants are subjected to in circuses or tourist locations or when they are used for begging on the hot, dusty streets of Indian cities. Yet even if we assume for the sake of argument that temple elephants are comparatively “well-kept,” we have to ask how well-being can truly flow from denying elephants the natural, community driven lives they were born to live free in the wild?

“Transfer of young elephants from their homeland to an alien location is always a bad idea,” says Ms. Suparna Ganguly, of Bengaluru-based animal rights organisation CUPA (Compassion Unlimited Plus Action). Years of working on issues regarding captive elephants have convinced her that elephants cannot be treated like objects for reasons of commerce, livelihoods or culture.

Ms. Ganguly also points to the particular harm caused by removing elephants from their habitats, which have wider significance for the Indian traditions that revere nature and environment. “Without elephants, forests, rivers and wilderness spaces will gradually disappear to mankind’s own destruction. To enslave such animals in intensive confinement for man’s petty uses is cruel and illogical.”

India has the highest number of Asian elephants of all nations, and the second highest population of captive elephants, after Myanmar, at approximately 2,650. Despite a clear national policy against further captivity of wild elephants and numerous regulations to protect them from cruelty, wild calves continue to enter captivity and private ownership.

The state of Assam is known to be a hotbed for the illegal capture and taming of wild elephants, especially when they are young calves. Elephants from Assam are often “given” to other states for supposedly short-term periods, never to return. Most captive elephants found across Indian temples or in private possession can be traced back to Assam.

Mr. M. N. Jayachandran of the Society of Prevention of Cruelty to Animals stated emphatically, “There is no such thing such as ownership of an elephant now. The elephants that are ‘owned’ are only illegally transferred. In their 2015 court order, the honorable Supreme Court of India clearly states that transfer of private ownership of elephants is illegal.”

Moreover, the certificate of ownership must be renewed every 5 years. “In Kerala, not a single certificate has been renewed,” says Mr.Jayachandran. “Hence any elephant that is being privately held captive here is illegal and undocumented. In spite of a statement given by the Forest Department stating that the elephants shall not be transferred to another custodian, they are very much being transferred.” Under the Wildlife Protection Act of 1972, the Forest Departments are custodians of all thing wild. No private individual or body can own a wild animal – but somehow we tolerate an exception for elephants, while also treating them as national heritage and worshiping them as quasi-gods.

The four baby elephants who are about to start their journey to Gujarat are on a path that goes against their natural interests, which is morally and legally dubious. This goes against the core belief of the Federation of Indian Animal Protection Organizations (FIAPO), which is that animals have intrinsic value and deserve to be treated with dignity.

We are committed to creating change in our perceptions of animals, from seeing them as commodities to sentient beings who are subjects of equal rights. Thereby, we strongly affirm that all animals must be entitled to a range of legal and constitutional rights, namely bodily integrity, autonomy, liberty and dignity. These core rights prohibit ownership of animals as things, their commercial exploitation and cruel and degrading treatment. At the very least, these core rights allow for an equal consideration of the interests of animals.

Featured image: a temple elephant on Shankumugham beach, Trivandrum, Kerala. Image credit Thejas Panarkandy, CC BY-SA 2.0.