The human side of the zoo’s orangutan exhibit is open-air, meant to feel like you’re out for a walk in the forest and have happened upon five well-fed orangutans lounging behind glass. Manicured plants grow in beds cut out of the concrete floor, which is textured and mounded and curves up to meet the concrete walls, themselves molded to look like the trunks of large trees. The back wall, painted to resemble a fence, has life-sized photo cutouts of an indigenous nuclear family posed in front of it in traditional garb. There’s a single lacquered section of log split into halves to make a bench, and a few short informational signs: a metal replica of an adult male orangutan’s enormous hand, a handful of sentences of information about orangutan social structure and anatomy, and a list of major companies endorsed by the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil.

The rest is just a lot of space for standing, which, on summer afternoons especially, will be filled with a loud, constantly shifting mass of people: stroller-pushers, picture-takers, glass-tappers, entire families on vacation, whole summer day-camps in matching shirts, and roving troupes of boys making monkey noises and beating their chests.

All of this faces several panels of thick glass, on the other side of which are two separate rooms, like large concrete bowls, reminiscent of skate parks with more man-made boulders and floor drains. From the ceiling hang loops of old fire hose, hammocks woven out of straps of industrial webbing, stiff artificial vines. Depending on the day, a few alternative variables: piles of those cheap brown paper towels, pulled off their rolls; big squares of burlap made from old rice bags; sections of white PVC pipes, in various lengths and shapes; scattered yellow hay, usually containing hidden bits of food; and orangutans, five in all, Bornean-Sumatran hybrids, two males and three females, ranging from 25 to 48 in age.

This was the same zoo of my childhood. I had come often with my mother, and then later with her and my young siblings. When I picked it as my research site, I thought of it as a familiar place. I even remembered seeing the same orangutans I would end up studying, years earlier, when I and their enclosure were both much smaller. A few days before I returned in my new researcher-role, I was in my advisor’s office, clearing a space for myself to sit among her monkey books, monkey calendars, monkey mugs, monkey figurines and monkey paperweights.

“Alright,” she said, “Here’s rule number one: no interacting with the orangutans. You go there, you ignore them, you don’t make eye contact, you don’t interact with them in any way, no matter what.”

It seemed straightforward enough at the time. I don’t remember questioning the rule at all, and it had the weight of authority behind it: both my adviser’s, and everything I’d read on so-called objectivity and habituation.

But there would be eventual objections.

Two weeks into my time at the zoo, I was standing in my usual spot, holding my clipboard. The crowd was thin that day, and an orangutan named Chinta pressed her face against the glass, staring at me. She knocked on the glass. There was no ambiguity; the gesture begged a response. I looked off into the distance, trying not to betray the tension I felt between my gut and my training.

She knocked again.

She knocked, and knocked, and knocked.

I wrote down that she was knocking and did nothing else.

She knocked with both hands at once. She looked irritated, baring top and bottom teeth, and walked away. I felt I had missed an opportunity. I felt I was keeping myself from the understanding I claimed to be seeking. I felt I had ignored someone as they reached out to me. I felt I had been rude. This played out three more times that day, and then over the next several days as well.

It would be at least another year before I read primatologist Barbara Smuts describing how, towards the beginning of her career, she came to be accepted by the wild baboons she studied. While she had been coached to ignore them, just as I had with the orangutans, it quickly became clear to her that this made the baboons more wary of her presence. She had a breakthrough when she entered into a responsive relationship with them, when she learned to “speak baboon,” to send and receive some of the messages the baboons communicated with their eyes or body language. This could be as simple as moving further away after a dirty look from a baboon, rather than sitting there unresponsively like a rock. This “signaled a profound change from being treated as an object that elicited a unilateral response (avoidance), to being recognized as a subject with whom [the baboons]could communicate.”

Over a decade after Smuts published this, it had apparently not changed much about the ways new students were being trained. In my case, even when the main focus of my research was on interactions between humans and orangutans, I was discouraged from acknowledging the orangutans as social subjects, or communicating in any way with them. But Chinta reminded me incessantly of her subjecthood. Knock: I’m here. Knock: I’m here and I see you. Each knock was an invitation, an acknowledgement, a willingness to open some kind of conversation. She seemed to be wondering, though, if I was capable of the same in return.

***

Chinta and her twin brother Towan were born in 1968. The twin orangutans were raised alongside two baby gorillas by zoo employees. I don’t know whether the zoo employees-cum-surrogate ape parents still visit, or whether they are even still alive, and I don’t know the story of Towan and Chinta’s mother, though her inability or unwillingness to raise her babies herself is common enough in zoos to hardly be considered a story at all.

Heran and Belawan, several decades younger, were raised by their orangutan mother. This upbringing seemed to have given them a radically different outlook on the humans they were constantly surrounded by. I never saw Heran show interest in a human, except when the keeper brought meals. He often sat with his enormous back to the viewing glass. His sister Bela spent most of her time covered by a piece of burlap, often lying in the tunnel that connected the outdoor yard to the indoor enclosure, which was one of the only spots where she was completely out of sight from the viewing area and could not be looked at. When preparing to settle in, she’d gather armfuls of hay, pulling it in around herself until most visitors would trail by the enclosure, wondering aloud where the orangutans were.

Bela was now housed alone with her father, Towan, separated from the others since adolescence due to her disruptive temper and propensity towards biting. The only thing that roused her from her tunnel with any enthusiasm was when Towan sat near the glass and stared out at human visitors. Then, seemingly enraged, Bela would swing towards him like a biting pendulum, slapping him and throwing hay, sometimes even grabbing his fleshy cheek pads with both hands and manually pulling his gaze away.

Bela’s rage was roused with a particular intensity when Towan interacted with human women, something he did often. I had been told early on by a smirking docent that Towan was a “dirty old man,” that in the evenings when they settled downstairs before sleeping, and the orangutans were given magazines to look at, Towan always went for the Victoria’s Secret catalogs. In the summers, he’d drop down to the floor of his enclosure, which was several feet lower than the viewing area, and peer up visitors’ skirts.

Towan spent most of his time laying on a wooden platform built right up against the viewing glass, around face-level for most visitors. Facing the crowd, he’d lock eyes with someone, most often a woman, though like the other orangutans he had a strong interest in children and babies as well. I saw what followed play out similarly more times than I could count. Eventually someone would get caught, struck by his intense eye contact. I saw people spend an hour or more transfixed by him, staring into his eyes with less than a foot and a layer of glass separating them. I saw people cry, or become speechless; I saw people urge their group to go on and enjoy the rest of zoo without them while they stayed just a little bit longer. And Towan just sat there and looked back at them while they trembled.

All kinds of people got stuck in that gaze. When I talk about my research at the zoo with locals, they often have a Towan story. My wife told me about volunteering at the zoo as a teenager, standing stunned with her hand to the glass, Towan’s hand pressed against it too, mirroring hers. In an interview on a morning talk show, actress Karin Konoval appeared to promote the film Rise of the Planet of the Apes, but spent most of the interview talking about Towan. Konoval first visited Towan to learn how to become him for her role as Maurice the orangutan. During her first visit, she says Towan came up to the viewing glass, pressed his face against it, and studied her closely for twenty minutes. When asked by the cheerfully bemused host what happened during those twenty minutes, Konoval says, choking up, “I really couldn’t tell you… Once Towan and I linked eyes, it was really moving … He gave me a great deal.”

Huddled around the orangutan enclosure, the zoo docents tell me that if you know Towan, you see him in Konoval’s performance of Maurice. In hushed voices they add that the movie is actually quite critical of primates in captivity. They decline to speak more on that subject.

As I meet more people who have been transformed by a captive orangutan’s gaze, I think often of what Harlan Weaver writes on “uneasy love,” how he says that “uneasy and noninnocent loves are central to the becomings that emerge from human and nonhuman animal encounters.” Weaver explores uneasy love between homeless people and their dogs, a pairing that upends most ideas about the proper way for people to live with and care for dogs. But there is love there too, and perhaps, as Donna Haraway notes, it is not an anomaly for love to exist in uneasy ways, as love is “often disturbing, given to betrayal, occasionally aggressive, and regularly not reciprocated in the ways the lovers desire.” Despite our romantic imaginings, maybe it’s not unusual for love to not be easy, to not even always be kind or just. When it comes to love between humans and nonhuman animals, where so many encounters happen on unequal ground, it seems this uneasy and ethically murky love might be the most common type of all.

The zoo, of course, is no exception; loving these orangutans, in this space, has an unsettling quality. Bonds develop through a thick layer of glass between humans who pay to visit and orangutans who could not leave if they wanted to. Relationships form in an institutional setting that exists to display animals to be looked at. The subject/object distinction intended here is occasionally disrupted in moments when the animals look back.

Konoval, the actor, visits the zoo regularly now, spending hours each time painting and sitting with Towan and the other orangutans. Her public Facebook profile, which presumably exists to promote her acting, mostly contains posts about great ape conservation. She’s quick to deflect praise or admiration for the often socially unintelligible act of becoming friends with an orangutan. She seems almost embarrassed over the attention, uneasy. In an email she stresses the asymmetry of the arrangement: “What I learn from them … and the ways the relationship each of them offers enhances my life, is I’m quite sure far more than I could ever give in return.”

***

Konoval isn’t the only regular here. Certain visitors prompt immediate reactions from the orangutans, especially Melati and Chinta, the two older females. These visitors don’t act like most of the rest. They approach slowly, often standing at first behind the crowd, which presses in tight against the viewing glass. The regulars wait until they are summoned by an orangutan—and if they are familiar, they will be, nearly without fail. If Melati or Chinta spots one of them, they will lock eyes and convene at a meeting place, usually around a corner where the crowd is thinner, though the masses will inevitably follow. Approaching one another, they will sit on either side of the glass, only inches apart.

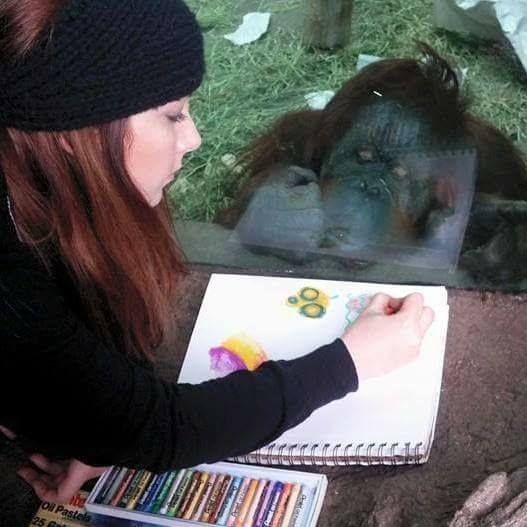

These visitors usually bring backpacks or purses. One had a rolling suitcase. Each of these bags holds variations on a theme: things these orangutans like to look at. The bags solicit enthusiastic volleys of knocks on the glass. They are opened to reveal riches in objects, presented one at a time. These are some of the things they bring: glossy books of photos, bubbles, sketchpads and markers, mints (to be displayed on the tongue, as prompted by an open-mouthed gesture from the orangutan), lotion (to be applied to the visitors hands, mimicking the lotioned hand rubs the orangutans get from the zookeeper to soothe their dry skin), playdoh, small mirrors (perfect for an orangutan to inspect her teeth and the insides of her nostrils), battery operated fans and light-up toys, hairbrushes, keychains, and anything bright pink or purple. Sometimes they just sit and have a look at one another. Some of these visitors have been coming regularly for over ten years, and when they arrive the orangutans’ look of recognition is undeniable. The zookeepers disdainfully call them “orangutan groupies.” But what else is friendship, besides choosing repeatedly to spend time with one another?

***

I had planned to interview the zookeepers early on; after all, I figured of anyone at the zoo they probably knew the orangutans best. I learned quickly that they were difficult to access, distrustful of researchers, and on top of that, had a surprisingly negative view of the sort of human-orangutan interactions my study revolved around. Like most of the zoo employees I encountered, they were fully committed to “naturalism,” which is characteristic of the modern zoo. Everything must appear natural; even the concrete was textured to appear organic. The division between nature and culture, and human and animal held strong here. A human friend toting a suitcase full of toys was not considered a natural part of an orangutan life, so these interactions were seen as undesirable and stressful.

I was given the zookeepers’ contact information by the head of research at the zoo, a new employee with fresher, more flexible ideas, who warned me that I may have difficulty pinning the keepers down. They never returned my emails, and I never got those interviews. At the end of my study, I brought my results to the zoo’s head of research. I had spreadsheets full of data that showed that actually, the orangutans were initiating and guiding the interactions with visitors much more often than humans did, and then they maintained control over the contents of the interactions, by pointing and knocking, or leaving if their human partner didn’t follow their directions. She was stunned, and agreed that this meant the zoo needed to change its attitude about what was going on here. She asked me to give a presentation to the zookeepers about what I’d found. They refused to attend.

Along with unexpected estrangements, I was pulled into unlikely alliances, and the politics of the zoo continued to surprise me. A month into my time there, one of the docents, who had been eyeing me somewhat suspiciously, sidled up next to me. We were standing on the boardwalk overlooking the outdoor enclosure, and she addressed me while we remained side-by-side, facing forward, like two spies having a public rendezvous. “You see that stump?” she whispered. She told me it used to be Melati’s favorite tree, as it was right on the edge of the outdoor yard, and she’d always sit in the high branches and watch people walk by on the boardwalk. The zoo had recently cut it down, with no plans to replace it, and now Melati seemed depressed, spending much of her time lying around inside. “Here’s what you need to do,” she urged, looking around before continuing, “go on the zoo website, and file a complaint. Say you’ve noticed her tree is missing and that she seems upset. They won’t do anything otherwise.” Before I had a chance to respond, she walked away.

***

If given the opportunity, Chinta will look inside visitors’ ears for hours. “Alright,” a docent booms, “Doctor Chinta is in!” Chinta’s sitting on an elevated wood platform, flush up against the viewing window, and peers out, looking expectant. The docent has to encourage the giggling crowd at first to present their ears, but once one person tries, pressing one ear against the glass near Chinta’s face, everyone wants a turn. Chinta brings her face in close, tilting her head back and forth, seeking the best view, and then raps her knuckles against the glass to signal when she’s finished, ready for a new ear. She’ll go back and forth between someone’s ears this way, knock and turn, knock and turn, until someone gets bored. She’s never bored first.

None of the other orangutans show any interest in ears. Most of them, however, have at least some interest in art, most of all Towan. He watches closely while repeat visitors draw and paint for him, sitting as near as possible, sometimes bringing along a head of romaine or handful of carrots and munching them like a movie-goer eating popcorn. Sometimes the zookeeper gives him big sticks of sidewalk chalk or plastic tubes of nontoxic paint. He tastes the paint as he goes, staining his lips a bright blue or purple. While painting Towan becomes very still and deliberate, appearing totally purposeful in each small movement of the brush or chalk. After finishing, the zookeeper trades him a bit of food for the painted canvas, which then gets auctioned off to raise money for the zoo.

The only time Towan isn’t out making appearances, we all know something’s wrong. It’s a slow day, and only a visitor or two come through the orangutan exhibit every half hour or so. A docent stands near one of the enclosures, one of several women who eventually turned her years of visiting the orangutans into a regular volunteer position. She’s supposed to be spending time where visitors are congregated, though today that’s not many places, maybe the kangaroos or the parakeet house. Instead she’s been standing here nearly an hour, looking into Towan’s enclosure. The zookeeper is standing on the other side of the bars at the far end of the enclosure, offering treats normally reserved for special occasions. The usual carrots and heads of romaine lay untouched, and the zookeeper produces raisins, frozen dixie cups of juice, globs of peanut butter on the ends of popsicle sticks. These are delicacies. Towan remains out of view. The zookeeper keeps at this for a long time, speaking encouragingly to him, coaxing him forward. He doesn’t budge. The keeper eventually moves on.

It’s just me, Towan, and the docent. She catches Towan’s attention and lifts the front of her shirt just six inches or so. Her pale stomach comes into view, and the real attraction: her bellybutton. At the sight of this, his enormous, long-limbed body reanimates, his eyes widen. He pulls himself up onto an artificial vine just on the other side of the glass between them. He perches face-level with her, and they both lean in, kissing quickly on the lips with just the glass between them, his lips turned comically outwards. “There you are, big boy,” she whispers, pressing a hand to the glass. She gives me a quick look, not a playful one, but one about how she’s trusting me by doing this with me here, about how she’s judged me to be on the same team as her, and she’d better be right.

Philosopher of science Vinciane Despret has a piece where she discusses ethologist Konrad Lorenz and his now-famous study of geese, the one where he accidentally became the mother to a group of baby geese. Having watched them hatch, he returned the goslings to their mother, and they immediately erupted into distress cries and attempted to follow Lorenz. What we now understand to be imprinting had occurred the moment the newly-hatched geese saw Lorenz above them, and what inevitably followed was a period of time where Lorenz was constantly followed by a group of young geese who knew him as their parent. As in this example, uneasy bonds form between humans and animals even in settings where they are not supposed to. Despret argues that if we pay attention to these bonds, we begin to see “that the signs that define subject and object, what talks and what is talked about, subjectivity and objectivity, are redistributed in a new manner.” What does it mean, in a zoo, when the direction of looking through the glass reverses, and an orangutan looks upon a human body? What does it mean when an orangutan asks a question of a researcher? It is clear in these situations that, as Despret argues, a radical redistribution is occurring.

Back at the zoo, I am positioned in front of Chinta, Melati, and Heran’s enclosure, still playing the uninvolved, nonreactive observer. Chinta has been knocking on the glass at me today, but not with any urgency. It is a lethargic knock, originating in a slow turning-over of her wrist. All three seem lethargic today, depressed, if I were allowed to make that judgement. Some days they are like this, laying draped like large orange bathmats over various elements of their enclosures. Chinta and Melati stare glassy-eyed towards the slow procession of visitors, who mostly stop for a few seconds to mirror their deadened expressions back at them and then move on.

A young boy of three or so and his father stop in front of the enclosure. The boy has no trouble interpreting the two sets of eyes looking back at him with a hauntingly resigned look. “He’s sad,” he says, and after a pause his father says back with a soothing tone, “You know what, though? It’s ok.” His hand is on the boy’s shoulder and they are already moving past the window as he is saying it. On the zoo’s website, it positions itself as an institution of learning. I think this is partly true, but perhaps not in the way it is meant. I see this scene repeatedly: a child’s intuition and compassion is neatly smoothed over, he is taught gently the true order of things.

Chinta knocks again, and Melati stares at the ceiling. I don’t know what this place is, anymore, or what my place is in it.

***

I haven’t visited the zoo in several months when Towan dies. My formal fieldwork completed, my visits on my own time come in waves. Sometimes it is too much, I am too uneasy to go see them. The bag I bring when I visit them, a retired makeup bag filled with small toys and art supplies, sits on the top of my tallest bookshelf. The zoo blog is updated a few days after he dies: a persistent infection in his lungs, then an exam under anesthesia, during which he has died.

Online I find a photo of him as a baby. Black and white, not a stylistic choice but because for an orangutan he was old, much older than me, older even than my mother. He is side-by-side with his sister Chinta, both of them clenching their feet like little fists. It is very difficult to see them and not anthropomorphize them, make them into furry human infants, oversized diaper butts and all. They are each held in place by a zoo worker in sterile looking scrubs, their faces out of view.

Later I stumble upon his name, buried in a book I am reading for another project entirely. There is minimal information, but in the mid-nineties there was an escape attempt. Towan led the entire group out of the enclosure, and all five of them made it out, including Bela and Heran, who were still quite small then. Where were they going? Wherever it was, even having fire hoses turned on them didn’t make them turn back. They were eventually shot with tranquilizer darts and returned to the enclosure. A few years after that, he escaped on his own, and again met the hoses and darts, this time staying put until his death nearly twenty years later.

Hribal calls this type of escape attempt part of a “hidden history of animal resistance,” arguing that much more is going on here than the innocent accidents we are coached to see. I would add to this that alongside outright resistance, there is an equally hidden history of animal refusal. Carole McGranahan writes, “If resistance involves consciously defying or opposing superiors in a context of differential power relationships, then refusal rejects this hierarchical relationship, repositing the relationship as one configured altogether differently.” In the case of the zoo, no action available to the orangutans could do anything to oppose the structures that kept them confined. What they did find a way to do was to refuse their ascribed roles as objects to be looked at, void of agency.

I went to the zoo to look at primates, to turn their behaviors into numbers on a chart, as practice for a career spent doing more of the same. I didn’t expect many surprises, especially as I had been visiting this zoo my whole life. When I returned with a head full of the relevant scientific literature and a ready clipboard, it all seemed simple enough. Instead, I found a complicated world, with five orangutans at the center of a twisted web of relationships.

Within the walls of an exploitative, profit-generating institution, I saw refusal in many forms: a flash of bellybutton, a smear of paint, an official complaint filed over a felled tree, an insistent knock on the glass, even a day spent hiding under a pile of hay. And there was love here: the zookeepers’ defensive, jealous love; the orangutan groupies, carrying their bags of treasures year after year; an actress, shaken to her core by Towan’s gaze, trying to give back while always knowing it would never be enough; and the docents, pretending their allegiances were with the zoo, like guards coming to work each day and slipping the prisoners extra rations with a wink.

I don’t mean to romanticize it all. Let me be unmistakably clear: every day it became more obvious to me what an unjustifiable violence it was for such incredible beings to be kept inside those walls. And yet, even under such total constraints, they constantly found new and subversive ways to express themselves, to make choices, to proclaim themselves subjects, and to enlist all kinds of others in their struggle.

Featured image: Melati looks out into the visitor area. Image credit Kevin Schofield, CC BY-SA 2.0.