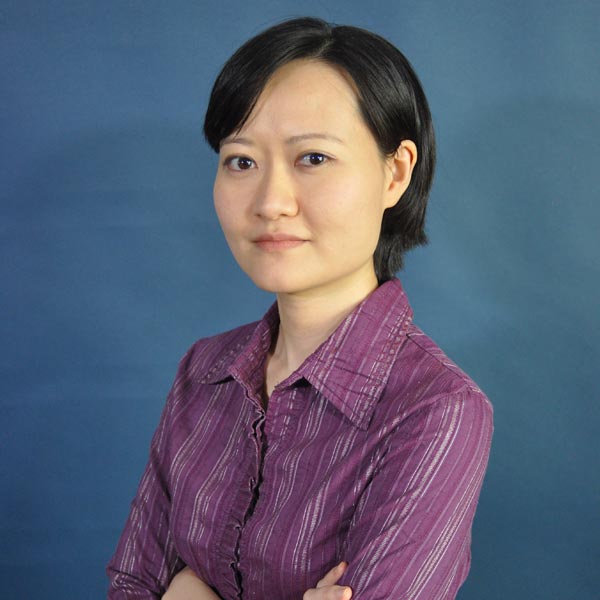

When Frances Cheng was working towards her PhD in physiology and biophysics, experimenting on animals was just how things were done. But then she started to question things, and she realized that her animal experiments were not only cruel, but also likely to teach her very little about human health. Along with this, she also learned that there was no place for someone critical of animal experimentation in her graduate program or her field of study.

Ultimately, Dr. Cheng finished her PhD, and moved on to dedicate her career to ending animal experimentation. She now works for People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) as a senior science adviser. Not only is Dr. Cheng an expert on the fight to liberate animals from harmful research, she also offers the valuable perspective of someone who was an insider and who knows very well how scientists are created by a system that trains them not to question animal-based research methods.

In an interview with Dr. Cheng, we discussed her “awakening” during her PhD program, whether change from within the scientific community is possible, and the important work she’s been doing since walking away from animal experiments.

Dylan Forest: In the documentary Test Subjects, you talked about how as a graduate student, you became disillusioned with your training when you realized the harmful medical research you were doing on rats didn’t translate to humans, and that in fact this is true of most animal research. Can you tell me about how this realization was received by your adviser and others you worked with?

Dr. Frances Cheng: When I became concerned about the translatability and legitimacy of my animal experiments, I raised this issue with my thesis committee—a group of faculty members who were assembled to help individual graduate students’ thesis research. These are the responses that I received:

- Professor B: (complete silence with an apparent look of agony)

- Professor C: “Your points are well-taken, but there is value in basic research.”

- Professor D: “Someone will find our results useful somehow, someday.”

- Professor T: “I’d think that students like you would just drop out,” implying that I should just quit the program.

- Professor X: “Your job as a student is to graduate and not think about [issues with animal cruelty and translatability].”

- My adviser Professor J (in private): “What am I supposed to do if not animal testing?” (Interestingly, I later learned that he’s not involved in research anymore and moved to an administrative role.)

Responses from my peers included one saying “but that’s how we get medicine,” another saying “to each their own,” another sympathizing with my breakdowns whenever I experimented on animals, to another helping me by taking away my laboratory duties related to animals.

You’ve been open about the psychological toll it took on you to harm and kill animals during the course of your research. Do you think this is common among people involved in this type of research, and how do you think about whether the people carrying out the experiments are victims too?

During my training, I knew that there was one other student who was timid about animal testing and was excused from it. I didn’t know anyone else who was similarly psychologically tormented by experimenting on animals, nor anyone else who was “emotionally immature” as some in the field would ridicule my empathy. I don’t think these crises of conscience are common because people who are strongly empathetic towards animals would likely not be in the field of animal experimentation to begin with, and the animal desensitization process throughout the biomedical training would either filter out empathetic people or transform them into “emotionally mature” experimenters who do not make emotional connections with the animals they torment. I was successfully desensitized, had my awakening during my PhD training, and I left the field right after I graduated. I believe, though, that all animal experimenters have the ability to “wake up” their moral compass, but the degree of psychological damage this would cause would likely vary.

I think animal experimenters are victims of a corrupt system. They have been repeatedly lied to and trained to use antiquated animal-based methods that overwhelmingly fail to advance human health. They have been used as pawns to perpetuate and strengthen the animal experimentation-industrial complex. However, unlike slaughterhouse workers who are also victims to the system and not readily able to shift careers, animal experimenters usually have the financial and educational means to choose a different path.

There’s a perception among the general public that the number one guiding principle behind science is the pursuit of truth, but unfortunately so often other factors come into play, such as politics, funding, and resistance to change. Why do you think there is such a strong resistance from within the scientific community to considering whether animal research is necessary or effective, even in light of growing evidence that it isn’t?

In the literature this phenomenon is called “lock-in.” There’s at least three types of lock-ins: technological lock-in, institutional lock-in, and psychological lock-in. Each of these includes multiple factors.

Animal experimenters might not know how to use, say, organs-on-a-chip [an alternative to animal experimentation]because it’s a totally different technology. Even with in vitro testing with human cells, which is one of the major category of non-animal research methods, it is fraught with animal-derived antibodies, xenogenetic culture conditions, and other tools that use animals directly or indirectly. There is a growing awareness that these contaminations confound in vitro tests with human cells, but we are still a long way away from making them truly animal-free, due to technological lock-in.

Research institutions have little motivation to eliminate animal testing because the current system is self-sufficient: Animal testing is used to publish papers; animal experimenters can use publications to apply for more funding; funding agencies (consisting of animal experimenters) fund more animal experiments; research institutions get overhead money from the grants and further support animal testing (e.g., with related infrastructure such as animal testing facilities); and funding is used towards more animal testing. It’s a vicious cycle, and industry plays a big role in this as well.

Confirmation and publication biases are some of the forms of psychological lock-in. Preferable data are chosen and published, whereas contradictory data or opinions don’t tend to see the light of day. This is why you rarely see negative data from animal experiments. Voices against animal experimentation are also suppressed. I have had personal experiences where editors asked me to agree with the use of animals in experimentation before my critiques on its scientific utility could be published. (Needless to say, my critiques didn’t get published.) There have also been multiple incidences where studies with human tissues were turned down by reviewers because they contradicted the animal data, despite the human tissue research being more relevant to human health. Animal experimenters can be so fixated on animal tests that they don’t think outside of the box (or cage). Other factors such as shame and guilt also play a role in animal experimenters’ psychological lock-in. (For some of these lock-ins, you can read more here and here.)

Pursuing truth is a good concept in theory, but it shouldn’t come at a lethal or harmful cost to others. There’s significant costs associated with animal testing, due to the loss of animals’ lives (directly), patients’ lives (indirectly), money, time, talent, and opportunity. Unfortunately many animal experimenters fail to consider others and are also of the mindset that any data is good data.

You wanted to include a dedication and apology to the animals killed during your research in your PhD dissertation, but you were discouraged and told it might affect your chances of graduating. These sorts of stories make me think that the scientific community is purposefully excluding those who are more critical of animal testing, which seems like a serious barrier to change. Do you think “change from the inside,” driven by scientists themselves, is possible under these conditions?

As a society, we have moved from horse-drawn carriages to cars and from typewriters to computers, but we’re still using the same antiquated animal testing methods from decades ago. The phenomena of self-purging and silencing the opposition is partly to blame. However, I think change from the inside is possible, though not easy. One example of change from the inside is through animal laboratory whistleblowers, who PETA frequently works with to create positive changes for animals and hold abusive individuals and practices accountable.

For example, a post-doctoral veterinary fellow at Columbia University informed PETA of cruel experiments being carried out on monkeys, in which experimenters induced strokes in baboons by removing the left eye of the animals, inserting a clamp into the empty eye socket and clamping shut one of the arteries going to the brain. PETA worked with the whistleblower to get video footage and documentation of the conditions in the laboratories and of the wrong-doing, and filed a complaint with the USDA. As a result, Columbia University was fined, one of the experimenters ended his experiments, the head veterinarian (the whistleblower’s supervisor, who had been ignoring her concerns and looking the other way when animals were mistreated) was fired, and the school was forced to hire a full-time primate behavioral specialist who was tasked with promoting the psychological well-being of primates. You can read more about this case here.

Also, if you look at human health research as a whole, there are also several governmental, academic, non-profit entities (e.g., the PETA International Science Consortium), as well as companies that focus on non-animal research methods. In a sense, these scientists are working from the inside, by persuading animal experimenters to change, providing funding and training for non-animal methods, and facilitating information exchange through conferences, meetings, and more. Many scientists working on animal-free testing methods also collaborate with animal experimenters or do animal testing themselves, for example to validate the alternatives. The definition of inside versus outside isn’t as black and white.

You’ve gone on to dedicate your career to ending animal experimentation, and you now work as a scientific adviser to PETA. Since you started working to end animal testing, what advancements are you most proud of having been involved in?

One of my early cases that I’m very proud of is the forensic experiments in New Zealand. Animal experimenters at a New Zealand government research entity and two other academic institutions were tying live pigs down on tables and shooting them in the head with semiautomatic handguns, to study the patterns of blood splatter. We stopped those experiments after a brief campaign, pointing out the blatant cruelty, how pigs’ heads are unlike human heads, and the myriad of existing non-animal methods that could be used instead. You can read about the case here and here.

With 18 international scientists who offered to lecture at our request, I helped organize a first-of-its-kind online course on non-animal research methods titled, “Biomedical Research Using Non Animal Models,” which is offered through University of California San Diego Extension. In addition to introducing various non-animal methods, this course also covers the futility of animal experiments, the ethical issues with animal testing, relevant laws and regulations, and how to effectively search for non-animal research methods.

Another project that I’ve been involved in is PETA’s Research Modernization Deal (RMD), which is a comprehensive document that summarizes the futility of animal testing in many research and regulatory fields, details the availability of non-animal methods, explains the costs of animal testing and benefits of human-relevant methods, and offers a strategic roadmap on how to move forward. This RMD has received numerous high-profile endorsements, such as from the National Medical Association and the National Hispanic Medical Association, among others. We’re encouraging governments in various countries to follow our suggested roadmap, similar to how the Netherlands has done and committed to stopping animal testing in many fields by 2025. I contributed to several chapters and presented the RMD in 2018 in a poster format at the 2nd Pan-American Conference for Alternative Methods in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Of course, COVID-19 is on everyone’s mind, and one of the noteworthy things about the rush to develop a vaccine is that animal testing is being bypassed. What are your thoughts on this development? It this likely to mean other research will forgo animal testing as well, or is it unlikely to generalize outside this context?

COVID-19 has reminded the world that it is not true that new treatments need to go through animal testing first before entering human clinical trials. It is actually not the first time that pre-clinical animal testing was skipped in the development of human therapeutics. In 1987, a drug therapy for AIDS called AZT was licensed by the FDA without animal testing, due to demands by patients. Thrombolytics for stroke treatment also went straight to clinical trials following success with treating heart attacks, which is a good example of drug repurposing that theoretically can bypass all animal testing.

In practice, there has always been bedside-to-bench (reverse translation) activities, and animal experiments and clinical trials are often conducted concurrently, as opposed to the linear direction from bench to bedside, as traditionally assumed. With animal data being drastically different from human data, and given the fact that 95% of all drugs that test safe and effective in animals go on to fail in human clinical trials, we should really question the usefulness of pre-clinical animal testing. With COVID-19, the feasibility of skipping animal testing is broadcasted, and I hope it will help spur more shifts away from cruel and ineffective animal testing.

One of the projects you’re working on is a campaign to end animal testing by food and beverage companies. What sorts of tests are these companies using animals for, and how can consumers be sure the food and drinks they buy aren’t made by companies who test on animals?

Food and beverage companies use animal tests to support human health claims – such as promoting weight loss, improving digestion, anti-fatigue, and many more – for marketing products and ingredients. Consumers are willing to pay more for products bearing health-promoting claims, and this increases profits for companies. Some companies also support curiosity-driven basic research that include animal tests.

We’ve discovered numerous animal experiments funded, conducted, or otherwise contributed to by food and beverage companies for studying common human foods, such as chocolate, ramen noodles, beer, probiotics and so much more. The experiments are egregious and cruel. Here are a few examples:

- Experimenters force-fed mice two prebiotics, forced them to preform 12 stress-inducing behavioral tests such as going through mazes, swimming, being hung by their tails, jumping from hot plates, and fighting with stranger mice, took their blood, and killed and dissected them.

- Experimenters fed mice a high-fat diet with or without a sesame extract, restrained them in tubes and cuffed their tails, starved them, injected them with glucose or insulin, repeatedly took their blood, forced them to run on treadmills with increasing speeds, electrocuted them to keep running until exhausted, and killed and dissected them.

- Experimenters starved rats, inserted a tube into their stomach and a catheter into their arteries, “fed” them milk peptides through the tube, measured their blood pressure through the catheter for an hour while they’re conscious, exposed or cut off their nerves, and killed them.

- Experimenters fed mice multiple antibiotics to kill off the microflora in their guts, force-fed them multidrug-resistant bacteria to induce lethal systemic infections, injected them with chemicals, force-fed them probiotics and prebiotics, and killed and dissected them.

- Experimenters starved rats, force-fed them extracts of apples, asparagus, broccoli, burdock, corn, green peas, mangoes, peaches, pears, pimento, pumpkin, strawberries, tomatoes, cabbage, carrots, or orange, force-fed them alcohol, took their blood, and killed and dissected them.

There are many non-animal methods that could have been used, including human tests, since these are common human foods with a safe history of use. In addition, these tests are not required by law. The relevant regulations in the US, Canada, European Union, and others actually require human data and not animal data for substantiating health claims.

Thankfully, avoiding animal tests for foods has become a global trend, as evidenced by our growing list of food and beverage companies, many of which are international. However, more needs to be done to eradicate animal testing in this industry. Consumers can check our list to avoid companies that test on animals for foods, or check the companies’ websites for animal testing policies. If you can’t find details on a company’s animal testing policy, or if the policy is lax, we encourage consumers to contact the companies and urge them to change. People can also help spur change by taking actions through PETA’s campaigns, such as the one against the MSG giant Ajinomoto, which has been tormenting thousands of dogs, fish, gerbils, guinea pigs, mice, pigs, rabbits, and rats in horrific and deadly food experiments since the 1950s.

What do you think are the most important steps in the current fight against animal experimentation? Where should we focus our energy to make the most progress for animals?

If I had a magic wand, I would make all current animal experimenters feel what I felt when I had my “aha” moment: that animal testing is morally wrong. Similar to how some people – after learning about the cruelty and other unsavory aspects of consuming animals – change their perception of animals as food to instead as being sentient once-living individuals, I couldn’t see animals in laboratories anymore as tools to generate data after I learned that animal data is not relevant to human health and indeed misleading. This realization made me vividly aware of all the harm to animals that I had caused, and I couldn’t run away from this inconvenient truth. So I decided to confront it head on by coming to work at PETA to help modernize biomedical research and end animal testing.

If I could only pick one area to focus on to improve the situation, I would say education for younger generations as well as consumers and voters. Education of young people is essential for creating a paradigm shift in how society views and treats animals. The systemic abuse of animals in our society has been around for centuries, and people who are entrenched in the system are harder to change. We need to bring young people in who are educated about non-animal methods and are not as indoctrinated about animal testing. Currently, many young people who don’t want to do animal testing tend to stay away from the health sciences as a career, and young people who wish to pursue health sciences don’t have enough opportunity to work in laboratories that focus on non-animal methods. We need to provide more resources and opportunities for people to embrace animal-free research methods.

Additionally, consumers and voters are some of the biggest driving forces behind progress for animals. For example, animal testing for car crash tests ended in the west more than 25 years ago because people vocally opposed it. Animal testing for cosmetics is also now virtually non-existent in the west because consumers demanded products not testing on animals. The California “lab-gag” bill that sought to prevent whistleblowers from shining light on cruel laboratory practices was defeated after citizens urged elected officials to block it. These are just a few examples of how we can promote progress for animals by educating the public and harnessing the power of the compassionate majority.

Featured image: A capuchin, formerly used in research, arrives at a primate sanctuary. Image credit Jo-Anne McArthur / NEAVS.