In 1956, young Anne Innis Dagg traveled alone to South Africa to study giraffe behavior in the wild. Not only was she embarking on one of the first observational studies of wild animal behavior, she also had to contend with the perception that this was a totally inappropriate undertaking for a young woman. Driven by a love and passion for giraffes and “a tremendous urge to see giraffes roaming free, instead of being cooped up in zoos,” Dagg overcame these odds and went on to build a tremendous amount of scientific knowledge about animals who very little was previously known about. In fact, she quite literally wrote the book on the subject: The Giraffe: Its Biology, Behavior and Ecology, published in 1976, is considered the foundational text on giraffes.

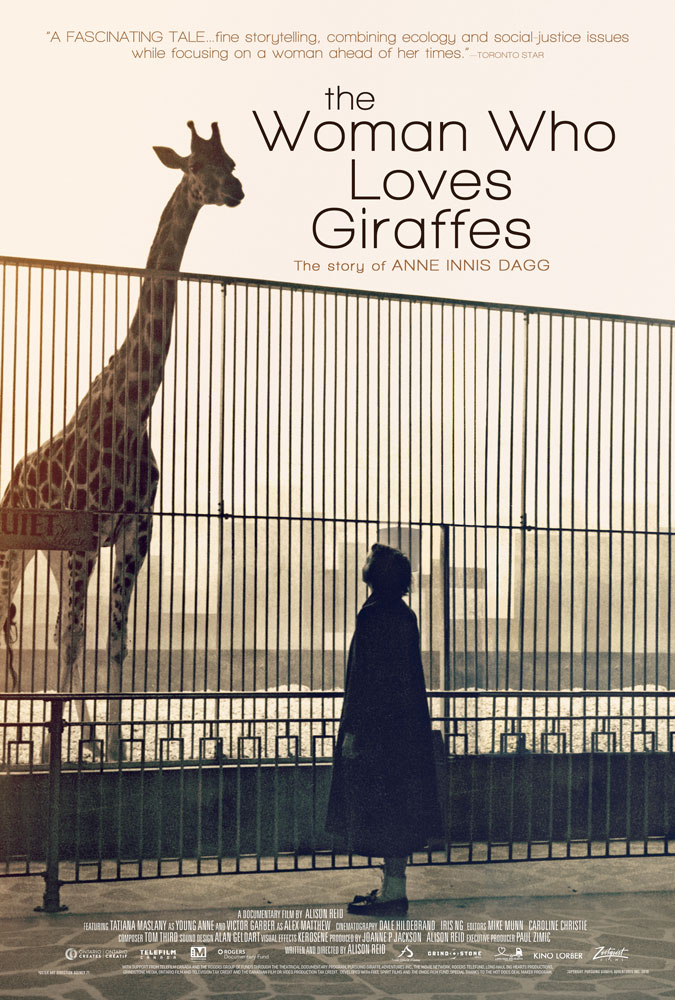

Despite this massive contribution, upon Dagg’s return to the United States and completion of a PhD, institutionalized sexism stood in the way of her securing a tenure position at a university, and she disappeared from the world of animal behavior science for many years. A new documentary, The Woman Who Loves Giraffes, which opens in New York City on January 10th, not only reintroduces the world to this amazing woman and her important work, but also shows what happened when she is pulled back into the world of giraffes, and learns that all along her work had inspired so many people who work with giraffes in various capacities.

It was a privilege to have the opportunity to interview Dr. Dagg and discuss her field research, giraffe behavior, and how things are different for giraffes over 60 years after she first saw them in the wild.

Dylan Forest: Your love for giraffes began as a child, when you saw them in zoos. What was it like for you when you first saw them in the wild?

Dr. Anne Innis Dagg: It was huge because I had wanted to see giraffes in the wild for so long. In 1956 it was very difficult to get to Africa to see them. When I finally saw my first wild giraffe by a pond drinking water I was incredibly moved. There is nothing like seeing them in their natural habitat surrounded by greenery.

What was it that drew you specifically to giraffes? Why was this your study species of choice?

It’s hard to know why you love something so much. I can’t remember exactly what it was about giraffes that captivated me, but I do know that when my mother took me to The Brookfield Zoo when I was four years old I was totally enamored by the giraffes, and from that point on it never left me. It may have been because they are so unique and so attractive, or possibly the way they move. They are so graceful and stately.

When you did your field research, you essentially had to invent a way to study animal behavior, as there were really no standard procedures or resources on this yet. What was it like to have this much control over your own research and methods, and what are your thoughts on how it’s different for people who study animal behavior now?

I think the interesting part was that it seemed so obvious that you should take the information from the giraffe’s point of view. Now they have all sorts of rules on what you should and shouldn’t do and I was just using common sense. If I was distracting the giraffe in any way then that would mean it wasn’t doing what it would be doing naturally.

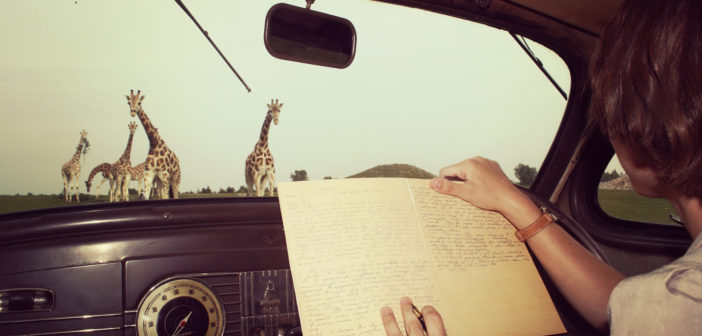

In 1956 I was recording behavior by taking hand-written notes every five minutes, whereas today scientists have technology like GPS devices that record statistics 24/7.

When you were working on your PhD, you knew you didn’t want to kill animals, as was common in studying biology, so you instead studied giraffe movement. What are your thoughts on the ethics of harming or killing animals in order to study them? Is it justified to kill an animal in order to understand them better?

I think animals should not be harmed in any way. If you have to hurt them then don’t do that research. Animals are sentient beings and should have the same rights as humans. After all we are animals as well.

You’ve spent countless hours observing giraffes. Is there something about them that you came to know in this time that would surprise most people?

I observed a male collecting urine from a female with with his tongue. This is how he tests to see if she is in heat and is ready to mate. It is called Flehmen behavior. I also observed males mounting other males, and later wrote a paper showing that homosexual behavior occurs in many species.

Your story of being a young woman going to Africa to study wild animal behavior at a time when this was completely unprecedented, and your immense contribution to knowledge about giraffes, the species you studied, is a very similar story to that of Jane Goodall. Yet as the film points out, your work is largely unknown by the public. Why do you think that is, that such similar stories received such different levels of attention?

L. S. B. Leakey, who was a well-known anthropologist, sent Jane Goodall to study chimpanzee behavior. National Geographic became interested and gave financial support, as well as sending a cameraman to film her work. In my case, I was functioning under my own steam with no outside financial support.

Dr. Griff Ewer at Rhodes University, who was a woman and didn’t have the same level of attention as Leakey, enabled me to find a place where I could study giraffes. Griff was hugely important to me, and she helped to organize my data after my time in Africa.

While your work may unfortunately be lesser known to the general public, that’s not the case among giraffe specialists. The documentary shows how you were brought back into the giraffe world, beginning with being given the pioneer award at a giraffe conference. Here you learned that you had been an inspiration to them and indeed had been like the Jane Goodall of their community. What was this like after so long, and after in so many ways your work and contribution had been devalued?

It was incredibly wonderful. It has been very rewarding to be brought back into the giraffe community! I now have many giraffe scientists and keepers with whom I can converse.

After reconnecting with the world of giraffes, you had the opportunity to return to Africa 50 years after you had last been there. I’m sure a lot had changed in that time. How had things changed specifically for giraffes since you did your fieldwork?

When I was originally in Africa I never dreamed that giraffes might become extinct. However, in recent years their numbers have plummeted. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species now lists giraffes as vulnerable to extinction, and at least two subspecies are listed as critically endangered.

There has been an 80% decline in the number of reticulated giraffe since 1998, and without drastic human intervention, the subspecies seems to be headed towards extinction. What do giraffes need most now? Where would you direct people who want to do something to help?

Anything that can be done to prevent giraffes from being poached for bush meat is key. Protecting giraffe habitat is also key to their survival. In order for giraffes and other wildlife to survive, local people must be involved in their conservation.

Please support these conservation organizations that are doing excellent work: Reticulated Giraffe Project, Save The Giraffes, and The Wild Nature Institute.

Featured image: Dr. Anne Dagg observes giraffes from her vehicle during her initial field research. Image courtesy of Zeitgeist Films.