Animal Aid’s newest campaign aims to educate people about the sensitivity of mice, how this sensitivity cannot be accommodated in laboratories, how mice deserve the same consideration as other animals, and how mice differ physiologically from humans in ways that render medical research on them meaningless. Animal Aid will also debunk other myths around the use of mice in research.

Why should you care about mice? Even if an animal is small, if we are unfamiliar with how they live in the wild or if they are not popular with the public, they should still be treated with consideration and care, just as larger, more familiar animals are, such as dogs and cats. Mice are intelligent animals who feel pain in a comparable way to people.

The Mice Matter campaign’s main focus is on the approximately three million mice who are bred, harmed and killed each year in laboratories in the United Kingdom (UK). Global estimates of the number of mice used in research are difficult to calculate, as different nations have different reporting requirements, and some countries, including the United States, exclude mice entirely from the number of animals they report using in research annually. One study co-authored by PETA estimated that around 100 million mice and rats were used in research in the United States in 2014. Though exact numbers are impossible to calculate given the data available at this point, it is clear that a staggering number of mice are used in research worldwide.

Two wild mice. Image credit belkin59, CC BY-SA 3.0.

Most people have no idea what mice are like outside of captivity, or the lives they are adapted to live in the wild. Wild mice may eat 200 small meals each night, visiting many feeding sites. They have many natural predators, so they prefer to stay close to cover and in contact with solid objects, in order to feel secure and protected. Mice are nocturnal, so they see best in very low light. Smell is their most important sense, and is used to find and assess both food and predators.

Mice are also highly social and usually live in family units. Male mice will ‘sing’ to females as part of the courting process. A female mouse may make more than 150 trips to gather material for a single nest. Mice are born blind, deaf and almost hairless, but they grow and develop fast, so that by four weeks of age, they are able to make brief trips out of their nest, usually accompanied by a parent. Mice are usually sexually mature at about six weeks old.

Laboratory cages can never replicate the complexity of life experienced by a mouse in the wild. No matter how ‘enriched’ a cage is, caged mice in laboratories cannot control where they explore, burrow, or escape unpleasant things. There is ample evidence that animals in laboratories, including mice, suffer due to their day-to-day living conditions. Even moving and cleaning cages causes stress in captive animals. Additionally, prey animals like mice tend to hide signs of pain or distress, which makes it harder to tell when their environment is negatively affecting them.

Laboratory mice are often kept in containers, stacked on racks, possibly with thousands of animals per room; the scale of suffering is enormous. Many terrible instances of unnecessary suffering were reported in UK laboratories in 2014 and 2015. Here are just a few examples: [These descriptions may be difficult to read.]

- Someone found a litter of ten new-born mouse pups, bred by mistake, so they tried to kill the pups by gassing them. The pups were not killed properly and were found, the next day, alive in a garbage bag.

- 26 mice were being transported, and were placed in 15 unsuitably small containers to move them. 30 minutes later, when the animals were being transferred to transport boxes, seven were already dead. The rest were so distressed, due to a lack of oxygen, that they were immediately killed.

- Someone thought they had killed three mice by bleeding them under anesthetic and then breaking their necks. The mice were taken to have tissue surgically removed and at that point it was observed that only one mouse was dead. Of the remaining two mice, one still had a beating heart and one recovered consciousness and moved. The mouse who moved had undergone a surgical incision in the abdomen, so they had experienced significant suffering.

A mouse used in experiments who has recently undergone brain surgery. Image credit Minyoung Choi, CC BY-SA 3.0.

The range of conditions and diseases which are induced and inflicted upon mice in experiments could fill countless pages. Genetically modified mice are bred in an attempt to ‘model’ human diseases such as Alzheimer’s. Mice are injected with cancer cells in attempts to cause cancer. Mice undergo damage to their brains to induce strokes. The list goes on, and the majority of experiments cause pain and suffering.

As well as being inhumane, research with mice is unscientific, as animal experiments do not reliably predict what would happen to humans under similar conditions. Mice are very different from humans biologically, including in many ways that mean the results of medical experiments on mice tell us nothing about human health. Mouse and human livers activate or neutralise cancer-causing substances differently, and the mouse lung is considerably different in structure from the human lung. Some common human diseases, such as mental illnesses and Alzheimer’s, do not occur naturally in mice.

Finally, even when they aren’t being used for experiments, just existing can entail suffering for laboratory mice. The various strains of mice that are bred to be used in laboratories are acknowledged to be associated with certain health conditions. Examples of these conditions include increased fluid around the brain, abnormally small eyes, skin lesions due to excessive grooming, heart problems and seizures.

Our Victims of Charity campaign is raising public awareness of the cruel and pointless animal experiments funded by some medical research charities. In one example, in October 2016 a research center founded with money from Arthritis Research UK provided a grant to support experiments on a number of ten-week old, male mice. The experiments involved operating on the mice to intentionally damage one knee of each animal. Animals mutilated in this way were killed over a period of time (between two to eight weeks after the operation). Many people who donate to medical research charities do not realize when their donations are supporting experiments which unnecessarily cause pain, suffering, and death to laboratory animals.

Unfortunately, even strictly behavioral research, which many people assume is less cruel, can cause significant suffering. In many cases inducing fear or pain is actually part of the design. For example, the Morris Water Maze forces mice, who are strictly terrestrial animals, to swim in a tank of water until they locate a surface platform on which to rest. The platform is subsequently hidden, and mice must remember its location, all while they are trying to escape through frantic swimming. In the hot-plate test, mice are placed on a surface consisting of a heated plate, then timed until they do certain things, such as licking their paws or jumping in an attempt to escape the heat. If these experiments sound like torture to you, that’s because they are.

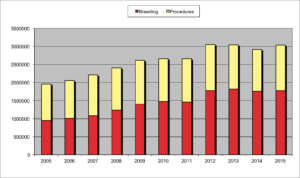

How has the use of mice changed over time? The above graph shows two categories of mice: the red bar represents those who were used for breeding but who were not used in further procedures, and the yellow represents those who were used in experimental procedures. The graph shows how the ratio has changed, and that the total has generally increased, over a decade. We can see from these numbers that the numbers of mice being used, whether for breeding or for experiments, is only going up. More and more mice are suffering for the sake of research that many people within the scientific community have called unsound and have called for alternatives to.

How has the use of mice changed over time? The above graph shows two categories of mice: the red bar represents those who were used for breeding but who were not used in further procedures, and the yellow represents those who were used in experimental procedures. The graph shows how the ratio has changed, and that the total has generally increased, over a decade. We can see from these numbers that the numbers of mice being used, whether for breeding or for experiments, is only going up. More and more mice are suffering for the sake of research that many people within the scientific community have called unsound and have called for alternatives to.

Most people don’t worry about the suffering that mice experience because of humans, even people who oppose experiments on other species, such as dogs or primates. There is no reason their suffering matters less than that of other species. Mice matter and they need your help. Speak out for mice when you learn about their use in experiments. Learn about other actions you can take on our Victims of Charity website, use our graphic on social media, and order leaflets from us to teach others about this issue.

Featured image: a mouse. Image credit George Shuklin, CC BY-SA 3.0.