“Can you prove you’re self-aware?”

“That’s a difficult question, Dr. Tagger. Can you prove that you are?”

Transcendence

(© 2014 Warner Bros. / Alcon Entertainment, fair use)

__

We now know that many animals are highly intelligent, with the capabilities to solve problems, communicate, and form societies and cultures. Meanwhile, artificial intelligences grow ever more complex, with some already passing for human in conversation. And as space exploration continues to expand the frontiers of human knowledge, astrobiologists are hopeful that alien life – and perhaps even civilization – will be discovered in the near future.

It is only natural to feel amazement and admiration toward such incredible beings, both those we coexist with now and those we may encounter in the future. But should we feel concern for them? Does the intelligence of animals, aliens, or AIs mean anything for how we should treat them? The answers to such questions hinge on an even more fundamental one: Are such beings conscious?

What is consciousness?

You may have an intuitive sense of what it means to be conscious. After all, your very experience of life depends on it! But can you define it? If not, you’re not alone – scientists and philosophers have struggled to do so for centuries (sometimes using the word “sentience” instead). Even now, there are a range of possible definitions to choose from:

“Consciousness: The fact of awareness by the mind of itself and the world.”

(Oxford English Dictionary)

“Consciousness is the subjective state of feeling or thinking about objects and events.”

(Donald R. Griffin, zoologist, “Evidence of Animal Consciousness”)

“Sentience… a convenient, if not strictly accurate, shorthand for the capacity to suffer or experience enjoyment or happiness.”

(Peter Singer, animal rights philosopher, “Practical Ethics”)

“The fact that an organism has conscious experience… means, basically, that there is something it is like to be that organism… something it is like for the organism. We may call this the subjective character of experience.”

(Thomas Nagel, philosopher, “What Is It Like To Be a Bat?”)

At a minimum, most seem to agree that consciousness involves awareness and subjective experience. Some experts distinguish between two different types of consciousness: phenomenal or feelings consciousness, awareness of sensations, thoughts, and emotions; and self-consciousness or self-awareness, knowledge of oneself as a unique thinking, feeling individual. Not all agree, however. Some hold that awareness of one’s thoughts and feelings first requires awareness of oneself, meaning that all consciousness is by definition self-consciousness.

Even within the latter camp, there are strong divisions. Some claim that most animals are self-conscious, since many species show signs of subjective thoughts and feelings and so must also be self-aware. Others argue that since only a few species show direct evidence of self-awareness, most animals are not actually conscious at all.

Scientists and philosophers have long struggled to define consciousness. Most agree it involves subjective experience and awareness. Researchers differ as to which, if any, animals are self-aware, and whether they could be conscious without self-awareness.

Why does it matter?

“The question is not ‘can they reason?’ Nor ‘can they talk?’ But ‘can they suffer?'”

(Jeremy Bentham, 1748-1832)

Read any book or website on animal rights and there’s a high chance you’ll come across the above quote, from philosopher Jeremy Bentham. Animal rights activists believe that animals deserve moral consideration from humans, not because of their intelligence, usefulness to humans, or importance to the ecosystem, but because they are conscious beings who care how they are treated.

If you have ever had a pet animal, you probably take it for granted that they feel pain. Neuroscience confirms this intuition. Most vertebrates (including mammals, birds, reptiles, and fish) respond to pain in similar ways, and share the name neural structures and chemicals for processing it. Some invertebrates, including octopuses, crustaceans, spiders, and even earthworms, show symptoms of pain as well. Of course, not all pain is physical: emotional distress, and even long-term trauma, is well-documented in many animals as well.

However, there is a difference between the sensation of pain and the perception of suffering. Sensation is a purely mechanical process. Machines can be programmed to “feel” “pain,” that is to sense harmful stimuli and take action to escape it. But if their defenses fail, there’s no reason (yet, at least) to think they experience agony or dread over being harmed.

Suffering, on the other hand, is a matter of perception, or subjective experience. Only conscious beings can perceive pain as suffering. But for that matter, not all conscious beings perceive the same sensations the same way. When it comes to pain, the same sensation might cause unbearable suffering for one, mild annoyance for another, and even pleasure for a masochist, while people with certain types of brain injury may not perceive it at all.

We cannot say, then, that just because something feels pain it necessarily suffers. If animals, aliens, or AIs are not conscious, they cannot suffer, and their pain doesn’t matter in any moral sense. But if they do suffer, then their pain matters a great deal, at least from their own perspective. If we place ethical value on others’ experiences, then their pain should matter to us as well. This is why consciousness is so important.

Pain and suffering are not the same thing. Pain is simply a physical response to injury, while suffering is a conscious experience. Because suffering requires consciousness, the question of which beings are conscious carries enormous moral significance.

Why is it unknowable?

Let us revisit the Turing test. Earlier on, you spoke to another entity via text message, and had to guess whether you were conversing with a human or an artificial intelligence (spoilers ahead – go here if you skipped that part of the exhibit).

__

Your conversation partner turned out to be an AI, specifically Cleverbot. Cleverbot is one of the world’s most advanced AIs. A powerful offline version of the software has almost passed the Turing test, convincing people that it’s human with nearly the same rate of success as actual human beings.

You probably assume that other humans are conscious, because in general they probably act similar to you in other ways and, if you should ask, will tell you that they are. But is it safe to assume the same of Cleverbot? Does the fact that Cleverbot can talk like a human (at least sometimes) mean that it’s conscious like one?

Probably not. Cleverbot works by comparing what users say to a database of millions of lines of text, from which it selects the closest matching response. With each new conversation, it adds new material to its database, improving its ability to say the right thing in any given context. With a database large enough to contain every possible response to every conceivable statement, an AI like Cleverbot could hold its own in any conversation by purely mechanical means. It would appear to be conscious, without any need for actual consciousness.

Some philosophers would refer to Cleverbot as a “zombie.” Obviously this isn’t literal, for the AI lacks a flesh-and-blood body to die, let alone become undead. In philosophy, a “zombie” is a being that lacks any subjective experience, and is therefore not conscious, but simulates every observable sign of it. It illustrates that while we can observe evidence another being is probably conscious, the only way to know for sure is to be that creature oneself. Because it can only be experienced subjectively, consciousness is therefore inherently unprovable.

Could all seemingly conscious non-human beings be zombies? For that matter, might all other humans be as well? Could you yourself be the only conscious being in the entire universe? Technically, there’s no way to prove otherwise.

While consciousness is extremely important, both morally and scientifically, due to its subjective nature it cannot actually be proven to exist. At best, deciding whether another being is conscious is a matter of educated inference rather than hard fact.

Shifts in science

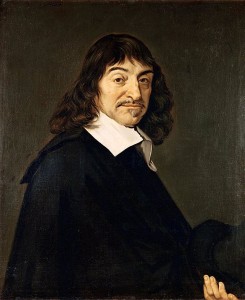

Consciousness can be experienced, but not directly observed. For this reason, many thinkers through history have believed it exists apart from nature. René Descartes (1596-1650) coined the term mind-body dualism, separating thoughts and feelings from the workings of the body. Like Aristotle and theologians before him, Descartes believed only humans possessed a mind. Animals were merely natural automata, machines operating by purely physical principles, devoid of thought or feeling. Descartes promoted vivisection, dissection of live animals, dismissing their expressions of pain as mere automatic reactions.

Though Descartes was highly influential for early modern science, his views on animals were not universally accepted. Biologists Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) and Charles Darwin (1809-1882) argued that humans are biologically related to other animals. Human abilities, including consciousness, should therefore be found in other species as well.

Descartes believed animals were not conscious, and Linnaeus and Darwin believed they were. But the scientific method relies on empirical testing, and because consciousness is not directly testable, some researchers came to believe it was not relevant to science. Because subjective experiences were unprovable, they considered them unimportant.

Ethically, this position served to justify widespread experimentation on animals, whose kinship with humans made them useful as medical models, without having to consider any moral dilemmas it might pose. Some scientists, such as biologist Ivan Pavlov (1849-1936) and psychologist B. F. Skinner (1904-1990), extended the same philosophy to human beings. They believed human behavior could be similarly explained in purely mechanical terms.

While scientists still cannot test for consciousness directly, the idea that it can’t be studied at all has lost favor in recent years. Jane Goodall’s 1960 discovery that chimpanzees use tools forced scientists to reconsider what other animals are capable of. Many mental abilities once thought unique to humans are now known in other species as well (See Among Us Already…). Advances in neuroscience now permit greater study of consciousness in humans, who can report what they are conscious of, linking conscious experience to types of brain activity seen in other species as well. Simpler experiments such as the Mirror Test can be used to infer self-awareness, a type of consciousness.

Many scientists now believe that consciousness can be reasonably expected of animals that show similar behavior and neurological activity to humans. The highly publicized signing of the Cambridge Declaration on Consciousness on July 7th, 2012 may come to be remembered as a paradigm shift in scientific opinion. Drafted by leading neuroscientists from NeuroVigil, Inc., Washington State University, Hunter College, Bennington College, the University of Queensland, and the Allen Institute for Brain Science, it reads:

Historically, scientists have held a range of opinions as to whether non-human animals are conscious, or whether it even matters. While consciousness still cannot be proven to exist, it can now be studied indirectly by various means. Many scientists today believe other animals are probably conscious.

NEXT: What Should We Do?