“You think this is the probe’s way of saying ‘Hi there!’ to the people of Earth?”

“There are other forms of intelligence on Earth, Doctor. Only human arrogance would assume the message must be meant for Man.”

Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home

(© 1986 Paramount Pictures / CBS Studios, fair use)

__

Thanks to ongoing advances in space exploration and computer science, we may hope to encounter extraterrestrial life, or create sentient machines, within the not-too-distant future. Yet for all our searching for intelligence among the stars, or striving to create it in a laboratory, we often fail to realize that the Earth already teems with intelligent beings: other animals.

For many centuries, scientists assumed that humans were the only intelligent species on Earth. It may appear self-evident that we are. After all, animals don’t reason, talk, or develop cultures or societies. Or do they? In recent decades, scientists have reconsidered many long-held assumptions about other animals, and discovered that many species are intelligent in ways never before thought possible.

Just how smart are animals relative to humans? Find out for yourself! See if you can measure up to other species in these six interactive challenges!

Challenge One: Tool Use

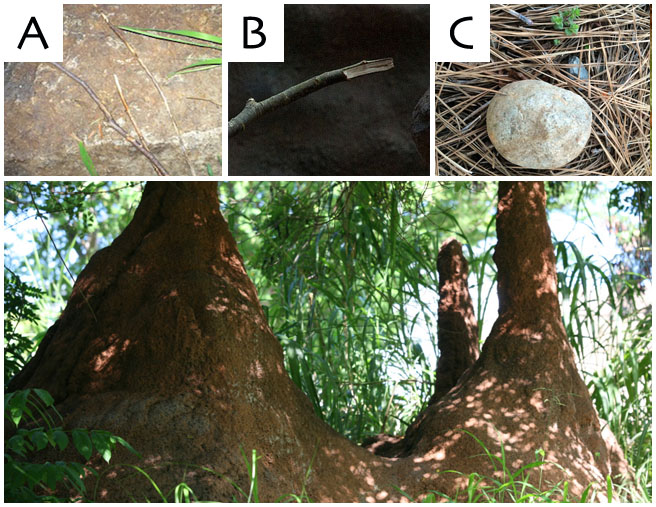

Imagine that you are a chimpanzee! You are hungry for termites, and need a tool to extract them from their mound.

Which of the tools shown above would you use for the job?

Good choice! Chimpanzees use long twigs to fish termites out of their mounds. Once thought unique to humans, tool use is now known in many animals, including mammals, birds, fish, and invertebrates.

The other two tools shown are a sharpened stick (B), which chimps use as a spear to hunt other animals, and a rock hammer (C), used to crack open nuts. Chimpanzees have also been observed crafting multi-purpose tools, and using combinations of up to five different tools to extract honey from beehives.

Though well known now, Jane Goodall's discovery that chimpanzees use tools was revolutionary in 1960. Until that time, tool use was considered unique to humans, and sometimes even our species' defining trait. Its discovery in another species was so shocking that archaeologist Louis Leakey, Goodall's supervisor, remarked, "Now we must redefine 'tool,' redefine 'man,' or accept chimpanzees as humans."

Today, tool use has been observed in many animal species, including other primates, elephants, sea otters, ravens, jays, octopuses, and even certain fish and insects. What would Leakey have said had the tuskfish been the first animal discovered using tools?

(Image credits: Photos A and C supplied by curator; Photo B by Steve Harris, used under CC BY-NC 2.0 / cropped from original; termite mound by Cliff, used under CC BY 2.0 / cropped from original)

Interesting choice, but it's not what a chimpanzee would use. Chimps use long twigs (A) to fish termites out of their mounds. Once thought unique to humans, tool use is now known in many animals, including mammals, birds, fish, and invertebrates.

The other two tools shown are a sharpened stick (B), which chimps use as a spear to hunt other animals, and a rock hammer (C), used to crack open nuts. Chimpanzees have also been observed crafting multi-purpose tools, and using combinations of up to five different tools to extract honey from beehives.

Though well known now, Jane Goodall's discovery that chimpanzees use tools was revolutionary in 1960. Until that time, tool use was considered unique to humans, and sometimes even our species' defining trait. Its discovery in another species was so shocking that archaeologist Louis Leakey, Goodall's supervisor, remarked, "Now we must redefine 'tool,' redefine 'man,' or accept chimpanzees as humans."

Today, tool use has been observed in many animal species, including other primates, elephants, sea otters, ravens, jays, octopuses, and even certain fish and insects. What would Leakey have said had the tuskfish been the first animal discovered using tools?

(Image credits: Photos A and C supplied by curator; Photo B by Steve Harris, used under CC BY-NC 2.0 / cropped from original; termite mound by Cliff, used under CC BY 2.0 / cropped from original)

Challenge Two: Face Recognition

Imagine that you are a chicken! Here are some photos of the other members of your flock:

Two of these are actually the same chicken. Can you tell which? Select those that match:

Nice job! Both these photos show Klinka, a pet chicken rescued by curator Wolf Clifton and his mother Kim Bartlett. Chickens and many other animals can recognize faces, an important skill for social order and communication.

Chickens' ability to recognize faces is important for shaping and maintaining the "pecking order," which determines each bird's food and mating access. Roosters will call out to hens when they find food, and hens use facial recognition to recall and preferentially mate with the best providers. They also remember and avoid males who call out deceptively, in an effort to trick them into mating (itself a sign of intelligence if not integrity).

Facial recognition is common to many other animal species. Primates, sheep, cattle, and dogs can even identify one another from 2D photographs. Many mammals communicate using facial expressions. While birds lack facial expressions, they can still communicate with their eyes, and some species can follow one another's gaze.

Surprisingly, even some invertebrates - wasps, bees, and crayfish - appear to use facial recognition to distinguish between friends and enemies!

(Image credits: Photo A and D © Kim Bartlett; Photo B by Mark Peters Photography, used under CC BY-SA 2.0 / cropped from original; Photo C by Elias Gayles, used under CC BY 2.0 / cropped from original)

Nope, sorry! The correct answers are A and D, both of which show Klinka, a pet chicken rescued by curator Wolf Clifton and his mother Kim Bartlett. Chickens and many other animals can recognize faces, an important skill for social order and communication.

Chickens' ability to recognize faces is important for shaping and maintaining the "pecking order," which determines each bird's food and mating access. Roosters will call out to hens when they find food, and hens use facial recognition to recall and preferentially mate with the best providers. They also remember and avoid males who call out deceptively, in an effort to trick them into mating (itself a sign of intelligence if not integrity).

Facial recognition is common to many other animal species. Primates, sheep, cattle, and dogs can even identify one another from 2D photographs. Many mammals communicate using facial expressions. While birds lack facial expressions, they can still communicate with their eyes, and some species can follow one another's gaze.

Surprisingly, even some invertebrates - wasps, bees, and crayfish - appear to use facial recognition to distinguish between friends and enemies!

(Image credits: Photo A and D © Kim Bartlett; Photo B by Mark Peters Photography, used under CC BY-SA 2.0 / cropped from original; Photo C by Elias Gayles, used under CC BY 2.0 / cropped from original)

Challenge Three: Language

Now you're a prairie dog! Listen to the three calls below, each of which describes a different potential threat.

"Coyote"

"Domestic Dog"

"Human"

Now listen to this call. What does it mean?

You... are... CORRECT!!!

Many animals have complex forms of communication. Prairie dogs come the closest known to having a full language.

Prairie dogs are not the only species to use different calls to describe different predators. Other squirrel species do as well, along with monkeys, meerkats, and chickens.

Some animals can learn much more sophisticated forms of communication. These include great apes, who can be taught human sign language; dolphins, who can understand complex electronic "languages;" and African grey parrots, who can not only learn over 100 words of English, but its grammatical rules as well.

In their natural setting, however, prairie dogs may come closest to speaking a "language" all their own. As shown in experiments by Dr. Con Slobodchikoff (the human above), prairie dogs do more than just use different calls for different natural predators. They can also use adjectives, modifying their calls to convey additional information. Prairie dogs can communicate whether an object is large or small, circular or triangular, and even whether a human is wearing a blue or yellow shirt!

(Credits: Sound files and photo of Dr. Slobodchikoff courtesy Dr. Con Slobodchikoff. Coyote photo by Larry Lamsa, used under CC BY 2.0 / cropped from original. Domestic dog photo © Kim Bartlett.)

You... are... INCORRECT!!!

The correct answer is "Domestic Dog." Many animals have complex forms of communication. Prairie dogs come the closest known to having a full language.

Prairie dogs are not the only species to use different calls to describe different predators. Other squirrel species do as well, along with monkeys, meerkats, and chickens.

Some animals can learn much more sophisticated forms of communication. These include great apes, who can be taught human sign language; dolphins, who can understand complex electronic "languages;" and African grey parrots, who can not only learn over 100 words of English, but its grammatical rules as well.

In their natural setting, however, prairie dogs may come closest to speaking a "language" all their own. As shown in experiments by Dr. Con Slobodchikoff (the human above), prairie dogs do more than just use different calls for different natural predators. They can also use adjectives, modifying their calls to convey additional information. Prairie dogs can communicate whether an object is large or small, circular or triangular, and even whether a human is wearing a blue or yellow shirt!

(Credits: Sound files and photo of Dr. Slobodchikoff courtesy Dr. Con Slobodchikoff. Coyote photo by Larry Lamsa, used under CC BY 2.0 / cropped from original. Domestic dog photo © Kim Bartlett.)

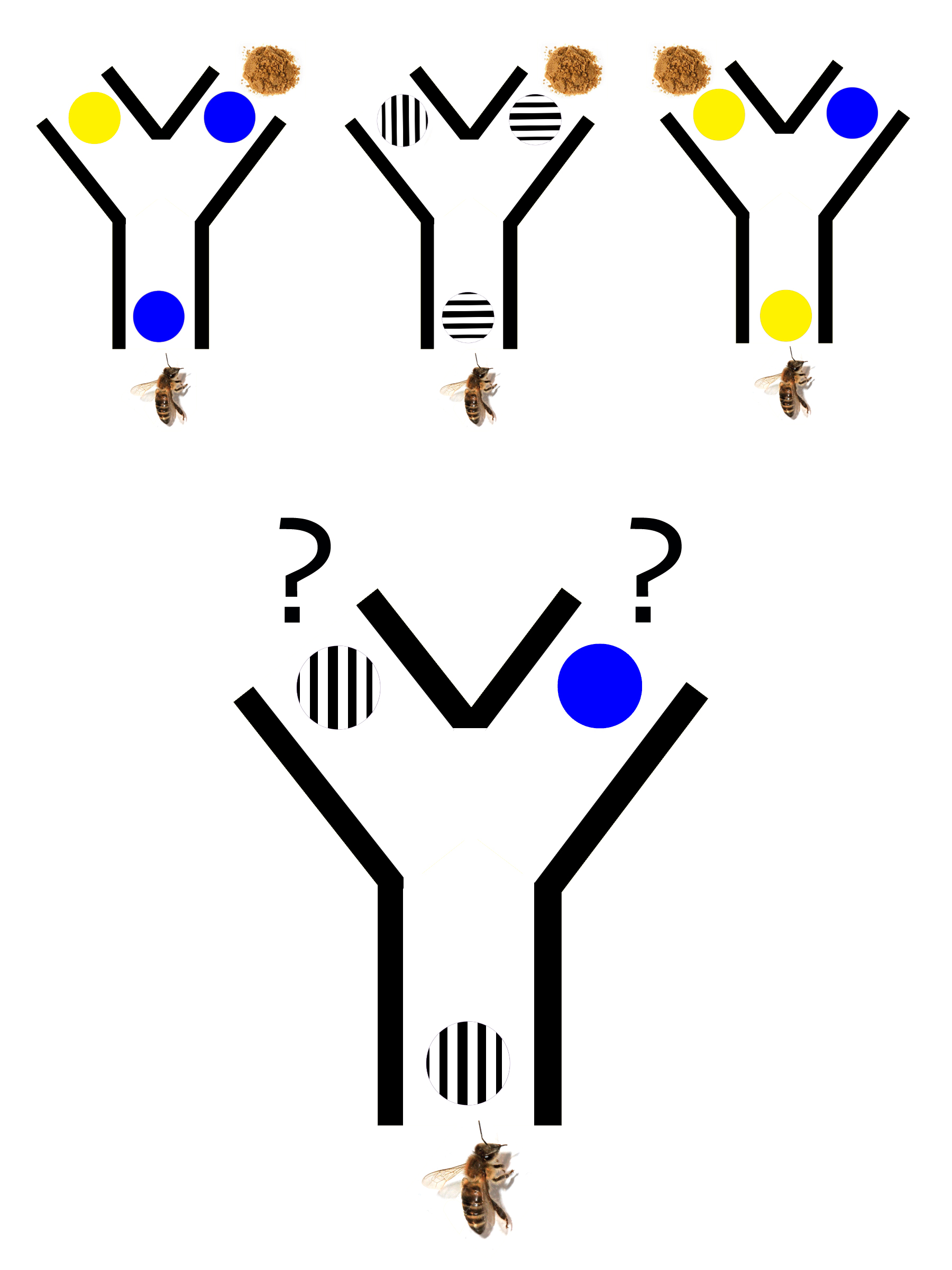

Challenge Four: Abstract Symbols

You've become a honeybee! Each of these mazes leads to some delicious sugar, if you solve it properly! Examine the first three, and see if you can tell what the correct routes all have in common!

Now solve the bottom maze! Which path leads to the sugar?

Yes! The symbol for the correct path is always the same as the symbol at the maze's entrance. Honeybees can solve this puzzle using abstract thought, despite having less than a million total brain cells.

The honeybee, whose brain is just a millimeter across and contain less than a million neurons, may seem a poor candidate for intelligence of any sort, let alone abstract thought. Yet honeybees can solve the puzzle shown above by learning the abstract rule "same symbols lead to sugar." They can also extrapolate across senses, so that a bee taught using colors will apply the same rule to odors as well.

Honeybees display other forms of intelligence, too. They can override their own instincts, learning in controlled settings to target differently colored flowers than they would in nature. In collecting nectar, they navigate using landmarks to guide them to and from the hive. They even communicate with one another through body language, using elaborate "waggle dances" to convey both the direction and distance of food sources and nest sites.

Such abilities demonstrate that even seemingly simple creatures, with only the tiniest of brains, can prove to be surprisingly smart!

Sorry, no sugar for you! Look at the top mazes again - the symbol for the correct path is always the same as the one at the maze's entrance. Honeybees can solve this puzzle using abstract thought, despite having less than a million total brain cells.

The honeybee, whose brain is just a millimeter across and contain less than a million neurons, may seem a poor candidate for intelligence of any sort. Yet honeybees can solve the puzzle shown above by learning the abstract rule "same symbols lead to sugar." They can also extrapolate across senses, so that a bee taught using colors will apply the same rule to odors as well.

Honeybees display other forms of intelligence, too. They can override their own instincts, learning in controlled settings to target differently colored flowers than they would in nature. In collecting nectar, they navigate using landmarks to guide them to and from the hive. They even communicate with one another through body language, using elaborate "waggle dances" to convey both the direction and distance of food sources and nest sites.

Such abilities demonstrate that even seemingly simple creatures, with only the tiniest of brains, can prove to be surprisingly smart!

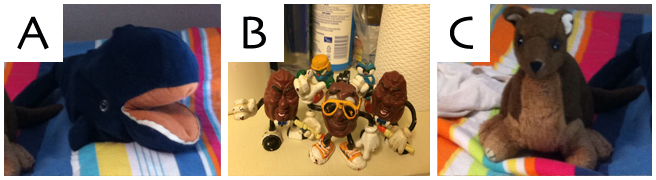

Challenge Five: Exclusion Learning

Now you're a dog! Specifically, a border collie. Here are some of your toys:

The stuffed coyote is named "Salem," and the California raisin figurines are the "Raisin Geeks." Which toy is "Pokintail?"

Yes, the whale is called "Pokintail!" You figured this out through exclusion learning; because you knew the names of the other objects, you could deduce that "Pokintail" referred to the one whose name you didn't know. Besides humans, only border collies, dolphins, and sea lions are known to learn by exclusion. Chimpanzees, our closest relatives, are not.

We can take at least two broader lessons from the rarity of exclusion learning among animals. One is that some forms of intelligence really are uncommon. Although many animals are intelligent in specific ways, few if any share the same general range of cognitive abilities as humans.

The other lesson is that evolution is not a vertical ladder culminating in our species. Intelligence has evolved separately in many different creatures. Therefore, even if our closest relatives seem to lack our abilities, this still does not mean that we are truly the only animals to possess them.

(curator's note: the toys chosen for this interactive, names included, were my own childhood favorites!)

_

_

_

Nope - "Pokintail" is the stuffed whale! If you had mastered exclusion learning, you could deduce that because you knew the names of the other objects, "Pokintail" must refer to the one whose name you didn't know. Besides humans, only border collies, dolphins, and sea lions are known to learn by exclusion. Chimpanzees, our closest relatives, are not.

We can take at least two broader lessons from the rarity of exclusion learning among animals. One is that some forms of intelligence really are uncommon. Although many animals are intelligent in specific ways, few if any share the same general range of cognitive abilities as humans.

The other lesson is that evolution is not a vertical ladder culminating in our species. Intelligence has evolved separately in many different creatures. Therefore, even if our closest relatives seem to lack our abilities, this still does not mean that we are truly the only animals to possess them.

(curator's note: the toys chosen for this interactive, names included, were my own childhood favorites!)

_

_

_

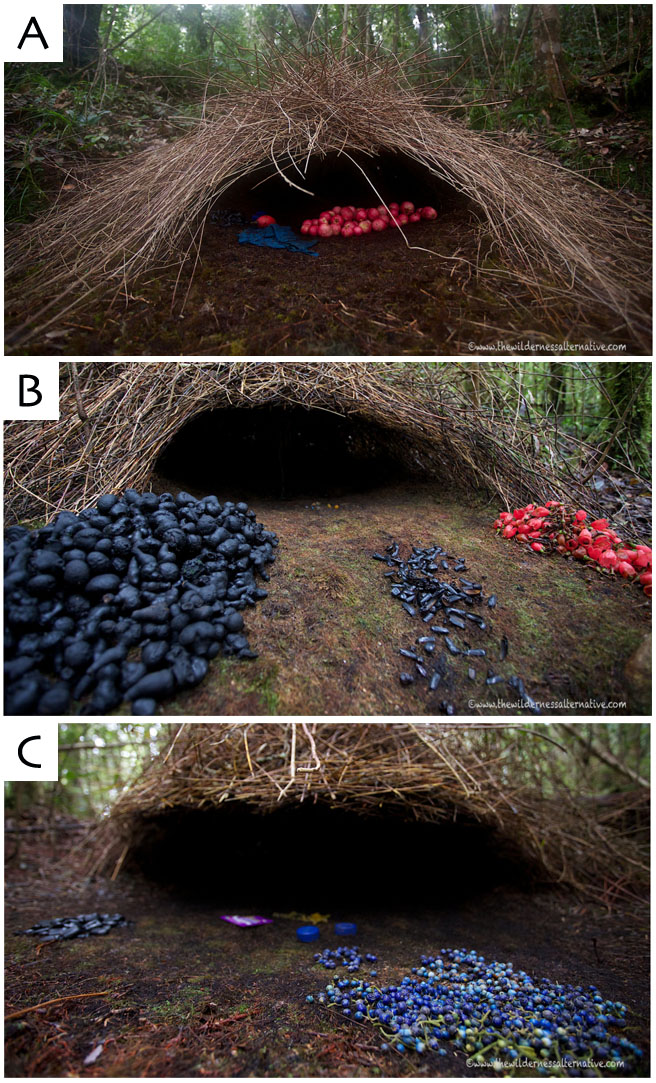

Challenge Six: Culture

Finally, you have become a female Vogelkop bowerbird! Male bowerbirds construct elaborate “bowers” to attract mates. Take a look at the beautiful bowers your suitors have prepared for you:

https://animalpeopleforum.org/beyondhuman/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Bowerbird-interactive-182x300.jpg 182w, https://animalpeopleforum.org/beyondhuman/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Bowerbird-interactive-620x1024.jpg 620w" sizes="(max-width: 656px) 100vw, 656px" />

https://animalpeopleforum.org/beyondhuman/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Bowerbird-interactive-182x300.jpg 182w, https://animalpeopleforum.org/beyondhuman/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Bowerbird-interactive-620x1024.jpg 620w" sizes="(max-width: 656px) 100vw, 656px" />

You may notice that certain bowers have proven more popular with other visitors. Our tastes for colors and shapes are partly conditioned by our cultures, evolving systems of behavior passed across generations. Bowerbirds and orcas also appear to have cultures!

Bowerbirds first learn to make bowers by imitating older males, but as they get older will experiment with different shapes and decorations. Different populations of Vogelkop bowerbirds, living in distant regions, vary widely in the designs of their bowers, showing the development of distinct cultures similar to human art styles.

Wikimedia Commons)

Orcas, or killer whales, also appear to have culture. Orcas living off the Pacific Northwest coast of North America have been classified into four distinct “clans.” These distinct cultures overlap in territory but use different sounds to communicate, feed on different prey animals, and engage in different types of play. Within each orca culture, there are multiple “subcultures,” smaller groups which vary their calls in a manner much like human accents!

(Image credits: Photos of bowerbird bowers © Yann Muzika, The Wilderness Alternative)

__

NEXT: