An interview with Kevin Schneider, Executive Director of the Nonhuman Rights Project.

Securing legal protections for animals against human cruelty and exploitation has always been a top priority for animal activists. Ashoka the Great, emperor of India from 268-232 BCE, enacted some of the earliest known animal protection legislation, including bans on animal sacrifice, hunting for sport, and the killing of certain species of wildlife. Several Buddhist rulers of China, including emperors Wu of Liang (502-549 CE) and Gaozu of Tang (566-635 CE), also passed laws restricting animal slaughter and promoting vegetarianism. Many centuries later, the modern Western animal protection movement crystallized around campaigns to enact animal welfare legislation. Early victories included the passage of the United Kingdom’s first anti-cruelty law in 1822, regulating the humane treatment of cattle and equines, and Henry Bergh’s founding of the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) to enforce the New York State animal welfare law in 1866.

However, recent years have seen a revolutionary new trend in animal protection law. Since 2013, the Nonhuman Rights Project has filed lawsuits on behalf of non-human animals in captivity – including four chimpanzees and three elephants so far – seeking a writ of habeas corpus. That is, a court order requiring a person’s captors to either free them (or, in this case, surrender the animals to a sanctuary where they can exercise their natural rights) or legally justify their imprisonment. This approach is novel in that, while existing animal welfare laws regulate how humans are permitted to treat non-human animals, a writ of habeas corpus on behalf of a chimpanzee or elephant would establish animals as having legal rights of their own, irreducible to human interests in treating them either cruelly or kindly.

Although to date, the NhRP has not won any of its court cases, it has prompted sympathetic opinions from judges who are, in theory, supportive of rights for non-human animals. Its strategy has also inspired similar efforts in other countries, several of which have resulted in victory, including writs of habeas corpus for an orangutan and chimpanzee in Argentina and a spectacled bear in Colombia.

Kevin Schneider is the Executive Director of the Nonhuman Rights Project. Animal People is honored to publish his detailed explanation of the Nonhuman Rights Project’s work and the importance of enshrining personhood for animals in the law.

Kevin Schneider (left), with Steven M. Wise (center), NhRP’s founder and president, and Buddhist monk Matthieu Ricard (right) at the 2017 Asia for Animals conference in Kathmandu, Nepal. Courtesy Kevin Schneider.

Q1: The term “animal rights” was first coined in the 19th century, and has been widely embraced by animal protection activists for many decades now. Yet it has only been relatively recently that serious campaigns have arisen calling for legal recognition of non-human animals as possessing rights. Why do you believe it has taken so long for animal rights advocates to begin laying the legal groundwork necessary for their movement’s agenda to succeed?

There’s no simple answer to this question. For one, people may take for granted the moral rights of nonhuman animals, but don’t necessarily see the need for transforming them into actual legal rights. They don’t understand that “moral rights” aren’t enough. In order for something to be a true right, it has to have “teeth,” that is, it must be directly enforceable in court. Another possible reason is that we simply don’t want to think about the depth of nonhuman animals’ suffering and its relationship to their utter lack of rights—it’s simply too distressing and overwhelming to contemplate.

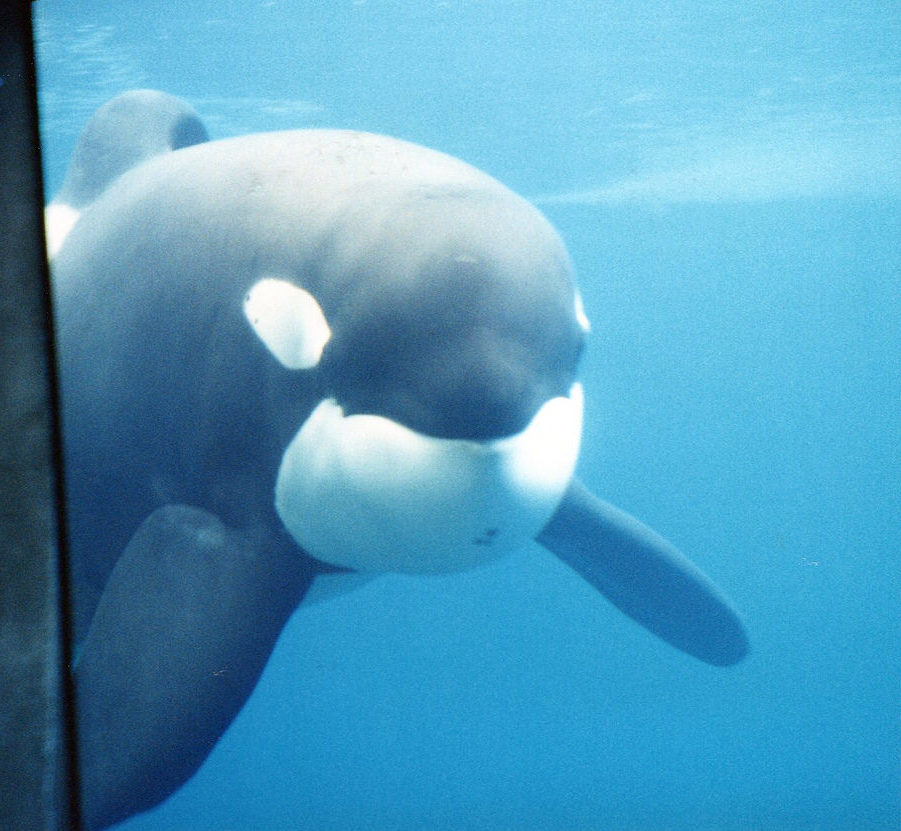

Keiko the orca (now deceased) at the Oregon Coast Aquarium in the early 1990s. Image courtesy Kim Bartlett / Animal People, Inc.

More to the point, the Nonhuman Rights Project is the first organization to call for personhood for nonhuman animals. This seems to crystallize the issue more than the more vague popular notion of “rights,” which has taken on many non-legal colloquial meanings in our culture. Moreover, the term “animal rights” itself is ofttimes hopelessly confusing, insofar as it implies that there is one set of “rules” that applies to all animals. The approach of the NhRP, then, is to embrace the complexity of the issue and litigate for “chimpanzee rights,” “orca rights,” “elephant rights,” and so on, winning recognition of rights appropriate to each species on their own terms, in as many places as we can. As science, morality, and public opinion continue to shift in our favor we will add as many nonhuman animals to the category of “persons” or “rights-bearers” as possible.

We definitely have a lot of education to do about why rights and personhood really matter for nonhuman animals and what that will look like in practice, but that process is well underway.

Q2: Within the animal protection movement, “animal rights” and “animal welfare” are commonly distinguished as two separate camps. Do you believe there is an intrinsic distinction between the two? If so, how would you define the difference between “animal rights” and “animal welfare” as causes? Does campaigning for animal welfare undermine animal rights, or vice versa? Or are they simply two different means to the same ultimate end?

Proponents of both animal rights and animal welfare want to help nonhuman animals. But under animal welfare, nonhuman animals remain legal “things” with no rights, because that status is never brought into question in a welfare or protection context. (Note that most if not all “sentient being” laws likewise appear to keep in place the legal thinghood of all nonhuman animals, often explicitly so.) History demonstrates that the only way to truly protect human beings’ fundamental interests is to recognize that they’re legal persons with fundamental rights. It’s no different for nonhuman animals. Animal welfare focuses on the duties imposed on human beings regarding how they should treat nonhuman animals. Animal welfare laws—which apply only to certain species in certain circumstances, often aren’t enforced, and typically require proof of intentional cruelty on the part of a human “owner”—are radically insufficient, in our view.

However, at the same time, until nonhuman animals’ rights are recognized, animal welfare laws are all they have, and so they’re absolutely necessary right now. But it’s past time we moved beyond this paradigm; it would be irrational and unjust not to, given all we know about the capacities of other animals and how we’re literally destroying them to serve human interests. Nonhuman rights prioritize nonhuman animals’ interests—in freedom from captivity, participation in a community of other members of their species, and their natural habitats—not ours. NhRP founder and president Steven M. Wise writes succinctly on the rights/welfare issue in his July 2016 article “Toward Animal Personhood” in Foreign Affairs.

Q3: To date, the Nonhuman Rights Project has focused exclusively on chimpanzees and elephants as clients. Your website cites “ample, robust scientific evidence of self-awareness and autonomy” in these species as a reason why. But what of factors such as established human relationships with particular species, or the severity of cruelty a given animal faces? For example, dogs have been ubiquitous in daily human life as companions and helpers since ancient times, and are so widely beloved that many people already recognize a sort of de facto “social contract” between humans and “man’s best friend.” Crows have passed many of the same cognitive tests used to demonstrate high intelligence and self-awareness in great apes and elephants, yet are routinely shot or poisoned in the name of “pest control.” What are the factors NhRP considers when selecting new clients? Do you have plans to represent species other than great apes or elephants in the future?

Western jackdaw, a species of crow, on the Isle of Man. Image courtesy Wolf Gordon Clifton / Animal People, Inc.

Absolutely. What we’re doing right now in the US—advocating for common law personhood and rights for demonstrably self-aware, autonomous nonhuman animals like chimpanzees and elephants—is a starting point. That’s what NhRP President Steven M. Wise means when he says we’re trying to “break a hole in the legal wall” that separates all humans from all nonhuman animals, which is as much about vindicating the interests of our nonhuman animal clients as it is showing people what’s possible, necessary, and just. We plan to follow the science wherever it takes us, developing and refining our legal arguments accordingly.

We focus our arguments, legal and factual, around autonomy not because we value it per se, but because there is a long and rich tradition of Western judges going to great lengths to protect it. While the container of that autonomy has hitherto always been a human being, science shows that humans are not the only autonomous beings in this world. We’ve maintained from the beginning that self-awareness and autonomy are sufficient, but not necessary, for recognition of personhood and rights—meaning there can and should be other bases beyond autonomy on which to premise personhood and therefore rights. However, we think it’s vital, especially at this very early stage, to support our arguments with robust, abundant scientific evidence, and any rights-based litigation on behalf of nonhuman animals must reckon with nonhuman animals’ thinghood.

That said, human experience—such as the relationships you describe—matters too, especially as far as the common law is concerned. (“Common law” is the component of a nation’s law based on judicial precedent rather than written statutes or regulations.) While we continue working in the courts, we are also in the process of developing rights-based legislation, which will allow us somewhat greater flexibility as to whose rights and what kind of rights we’re seeking. Efforts on behalf of “domesticated” species, including those most close to us by some measure, like dogs and cats, will likely require a very different paradigm. Because they are so intertwined with humans, a focus on “autonomy” as a basis for rights may not be appropriate, requiring something perhaps more along the lines of a quasi-citizenship model, where humans would take on various duties towards domesticated species.

The book Zoopolis by philosophers Sue Donaldson and Will Kylmicka is an excellent starting point for thinking along these lines (by the way, both contributed to the February 2018 philosophers’ amicus brief in favor of our New York chimpanzee rights appeal).

Q4: How have other animal protection organizations reacted to the Nonhuman Rights Project’s approach? Has the movement generally rallied behind you, or is your approach regarded as controversial by fellow animal rights activists? Are there any common criticisms you face that you would like to respond to?

Dr. Jane Goodall, a board member of the Nonhuman Rights Project, interacting with a baby working elephant in Nepal. Image courtesy Wolf Gordon Clifton / Animal People, Inc.

In general, people seem to be enthusiastic about and recognize the uniqueness of our approach. Some people are sympathetic but think our approach is unlikely to succeed. Some think we go too far, others not far enough. We’re not trying to please everyone; we’re doing what we think is most likely to succeed in court.

The fact is, in our New York court cases, we’ve already succeeded in overcoming procedural obstacles that animal advocates frequently come up against, such as having been granted standing without having to allege any injury to human interests. We also secured the first ever habeas corpus hearing on behalf of a nonhuman animal (chimpanzees Hercules and Leo in 2015), and in May 2018 a high court judge in New York, responding to another of our chimpanzee rights lawsuits, opined—for the first time that we know of in the U.S.—about the injustice of keeping all nonhuman animals “legal things” without any rights.

It’s important to keep in mind that our approach is tailored to the legal system we have, not the legal system one might wish we had. In the same vein, our approach will and must differ significantly from country to country, as you can see in Shirley Shtiegman’s July 2017 blog post detailing what some of our international legal working groups are researching and planning.

Q5: In the United States, certain non-human entities are already considered legal persons, including corporations, which may exercise rights such as freedom of speech and standing in court. Does this in your opinion establish any useful precedent for extending legal rights to animals, or are the cases of legal entities and sentient organisms unrelated? Conversely, do you believe there is any risk of campaigns against corporate personhood, such as the petitions for a Constitutional amendment that followed the controversial Citizens United court decision, ultimately redefining legal personhood in such a way as to specifically exclude animals along with other non-human legal entities?

The only reason we cite corporations (and indeed, cities, states, partnerships, ships, the Whanganui river, Hindu idols, mosques, Sikh holy books, the Colombian Amazon rainforest, the Ganges and Yamuna rivers, and other non-biological entities) as “legal persons” is to drive home the point that in the law, “person” and “human” have never been, are not now, and never will be synonymous. In other words, personhood is not a matter of biology, but rather a matter of public policy.

Cow beside the Ganges River in India. Image credit Aleksander Zykov, CC BY-SA 2.0

There is wide confusion about a fundamental issue at play in Citizens United (I personally think we’ll see it fall the good old-fashioned way, in the Supreme Court, way before any constitutional challenge could be mounted, which itself seems unlikely). There is a big difference between “legal personhood” and federal constitutional rights. The concept of corporate personhood has existed under the common law beginning in England 400 years ago or more. At its core, it’s a tremendously useful social innovation, insofar as it allows a profit-seeking enterprise (among many other types of entities, including charities and other nonprofits) to itself be owned, buy, sell, sign contracts, sue and be sued, be insured, and perform many other socially useful functions. That bit of legal magic, a “legal fiction,” has done, and continues to do, good things—including, for example, allowing nonprofits like the NhRP (which are themselves generally corporations of one sort or another) to thrive and serve as a counterbalance to for-profit and government interests.

The “mercenary sleight-of-hand” that transformed corporate personhood into federal constitutional rights occurred in the 1880s in the US with the Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad case, under the guise of the Equal Protection clause of the 14th Amendment (see Astra Taylor’s excellent piece “Who Speaks for the Trees?” for more context). Corporate rights, especially those said to exist under the US Constitution, can and should be reined in. That need not, however, require “throwing the baby out with the bathwater” and doing away with the fundamental idea of corporate personhood under the common law (and indeed, that would never seriously be considered in a modern liberal democracy anyway).

The conversation the NhRP has begun about personhood and rights is helping to cast light on all the other permutations of personhood and rights in our society. In order to recast rights in a more just and harmonious way, we have to first get a better collective grasp of what they are and why they really matter. All too often, judges and lawyers take for granted what a “person” is and fail to engage at all with the fundamental issues at play. But then, you come across a light in the darkness; someone like Justice Eugene Fahey of the New York Court of Appeals. On May 8th, Justice Fahey authored this opinion in one of our chimpanzee rights cases, a stirring and historic recognition of the justice and urgency of the arguments for nonhuman rights, which concludes:

“The issue whether a nonhuman animal has a fundamental right to liberty protected by the writ of habeas corpus is profound and far-reaching. It speaks to our relationship with all the life around us. Ultimately, we will not be able to ignore it. While it may be arguable that a chimpanzee is not a ‘person,’ there is no doubt that it is not merely a thing.”

As we’ve written elsewhere, the legal thinghood of all nonhuman animals is at least two thousand years old; yet in less than five years, we have already seen the first cracks begin to emerge in that ancient wall.

Q6: Outside the United States, there are a number of jurisdictions that have either recognized animals as “non-human persons” – as dolphins are now classified in India – or acknowledged legal rights for individual animals – including an orangutan in Argentina and a spectacled bear in Colombia. Are there any international cases you consider particularly useful as precedents for winning legal rights for animals in the United States?

Sandra, an orangutan held at the Buenos Aires Zoo in Argentina, was ruled a “non-human person” in October 2015, though the case was appealed and Sandra still has not been relocated to a sanctuary. Image credit Roger Schultz, CC BY 2.0

In short: yes! And we bring these rulings to the attention of the courts once we’ve determined that they have actual legal traction, as does the Argentine ruling that recognized Cecilia the chimpanzee as a person with rights and ordered her transferred to a sanctuary, where she now lives today. The dolphin declaration in India is more complicated and does not appear to have the force of law, though it is encouraging nonetheless.

The Cecilia litigation was modeled in part on the NhRP’s habeas petitions in the US, as was litigation brought on behalf of Chucho the spectacled bear and Sandra the orangutan. Those cases have not yet been resolved, but we’re keeping a close eye on them and are assisting Chucho’s attorney however we can. We are also doing all we can to support efforts outside the US that will lead to more declarations of nonhuman personhood, and we will continue to cite every example of it that comes from courts around the world. This includes most recently the decision of Colombia’s Supreme Court that the Amazon rainforest there is a “legal person” with the capacity for rights.

Q7: Do you believe there is an eventual need for an explicit legal definition of “personhood,” including criteria for what traits any given entity must possess in order to qualify?

No. The “genius of the common law” is its innate flexibility and openness to new discovery. There is no list of requirements for personhood. In fact, over most of its history, personhood (more to the point, the deprivation of it) has been used as a tool for oppression. Women, children, African slaves, Indigenous peoples, etc. were all at one time non-persons, that is, “things” in one way or another. After all, personhood is nothing more than the law’s way of saying “you have the capacity for rights.” That does not mean every “person” gets the same rights. Indeed, that is why even today it is possible for some humans to have rights (say to vote or drive) while others do not, due to age or some other legal disability. The same can be said of corporate persons: while a company can buy and sell and sign contracts, it obviously cannot marry.

Cockroach climbing a slippery slope. Image credit Arthur Chapman, CC BY-NC 2.0

Setting down a set of requirements for personhood (again, nothing more than the capacity for rights) seems to be born from a desire to stave off the “slippery slope,” for example the idea that granting rights to a chimpanzee will eventually dictate granting similar rights to a cockroach. The true antidote to that kind of fuzzy and reactionary logic is correct moral thinking and the conviction that we can find an optimal balance and process for expanding the scope of rights beyond the human. In the meantime, we should avoid creating any new walls and instead keep the door open for future societies to continue to develop. (See for example Justice Barbara Jaffe’s thorough and laudable rejection of the “slippery slope” argument raised against the NhRP by the New York Attorney General in the case of chimpanzees Hercules and Leo in 2015) Any effort to establish requirements or other barriers to personhood would by and large be to perpetuate the same evil we are fighting. We need to let social evolution continue and provide for future societies to continue to expand the ambit of rights.

From the standpoint of an attorney or a judge, a “person” is merely an entity with the capacity for legal rights. This definition has already been established. In a fundamental way, a “person” counts. Personhood is a tremendously flexible concept in the law. We argue that our demonstrably autonomous nonhuman animal clients are common law legal persons, with the fundamental right to bodily liberty, because the common law already demonstrates that autonomy is a sufficient requirement for personhood. We argue autonomy not because we decided it’s great, but because judges for hundreds of years have enshrined autonomy, and the protection of it in “persons,” as a supreme value of the common law. That makes it a powerful “hook” for us to argue on behalf of autonomous nonhuman animals. There are, and will be, other bases for rights beyond autonomy in the future. Autonomy, we believe, is a powerful starting place.

Q8: Venturing beyond non-human animals into more theoretical territory, do you believe entities such as artificially intelligent machines should also qualify for legal personhood, in the event that humans should ever create sentient, self-aware mechanical beings?

If you’re demonstrably self-aware and psychologically autonomous, the same moral and legal arguments apply, no matter who you are. These capacities serve as a sufficient, but not necessary, basis for legal personhood and fundamental rights to bodily liberty and integrity. We are asked about this often, especially over the last couple of years. See, among other similar examples of late, this NBC News story on “robot rights.” As noted, only time will tell what additional bases for rights beyond autonomy may develop.

“She Cyborg,” © AhMeD-19. Used with permission.

Visit the Nonhuman Rights Project’s website to learn more about its philosophy and ongoing campaigns.

Follow Kevin Schneider and the Nonhuman Rights Project on Twitter for the latest updates on the struggle for non-human legal rights.

Featured image: working elephants bathing in river at Chitwan National Park, Nepal. Image courtesy Wolf Gordon Clifton / Animal People, Inc.

1 Comment

Once our cats have been given personhood would it then become a crime to get them neutered because leaving the cat population to explode would decimate wildlife?

We are all fighting for habitat and the Human animal has spread itself extremely, some would say too widely, having stupidly relied in a charter on being responsible in its reproduction… it obviously wasn’t!!

Are all wild animals going to go extinct or will the other animal persons decree that Humans should leave them some space by getting the snip?

Is the Human animal itself on the brink of extinction as climate change has now turned into a runaway train?